Phytoestrogens and the Safety of Soy

Soy products contain compounds called phytoestrogens, which provide a wealth of health benefits—and a few potential risks.

Are phytoestrogens safe? The growing popularity of soy products in U.S. and European diets has raised considerable controversy. While the soy-rich diets of Asia generate documented health benefits, questions persist about the safety of soy in some products, especially infant formula.

To make sense of this debate, it helps to understand the nature of dietary compounds called phytoestrogens—plant-based compounds whose chemical structure resembles estrogens, the female sex hormones of mammals. Also called isoflavones, phytoestrogens are most prevalent in soybeans and red clover.

Phytoestrogens have been linked to better heart health and reduced risk of breast and prostate cancers. They can help with osteoporosis and menopausal symptoms and may possibly improve cognitive functions. For all these benefits, however, the question of whether we should consume more soy-based products or add soy supplements to our diets has not been fully resolved.

Let’s walk through the fundamentals of the phytoestrogens at the root of the soy-safety debate.

Phytoestrogens in Asian Versus Western Diets

Soy food, the main source of phytoestrogens, is common in Asian diets but rare in Western cuisine. Why does consumption vary so much? Different agricultural traditions and dietary preferences are potential answers.

People following a traditional Asian diet eat about 15–50 milligrams of isoflavones daily, much more than in the U.S. and Europe, where less than 2 mg daily is typical (Eisenbrand 2007). Asian cuisine uses primarily the first generation of soy products, such as tofu, soybeans and soymilk, while soy-based meat alternatives prevail in the Western diet.

The processing of soy products varies in Asian cultures: Unfermented soy products, such as soymilk and tofu, are popular in China, while fermented natto and miso are more common in Japan. Soy sauce prepared by fermentation is also prominent in Asian cuisines.

In addition to soy, several other plant species grown in the U.S. are rich in phytoestrogens. Groundnut, or potato bean—an essential staple in diets of Eastern Native Americans and later the Pilgrims—has the highest content of isoflavones among these species (Zaheer & Humayoun Akhtar 2017).

(Editor’s note: The name “groundnut” is used for various plants with edible parts. The scientific name for potato bean is Apois americana. ).

See also: Helping Clients Enjoy The Taste and Culture of Food

Effects on Inflammation and Metabolic Diseases

Experimental data show that phytoestrogens—including genistein, one of the main soy isoflavones—may be useful for treating inflammation, one of the basic mechanisms of metabolic syndrome, athero—sclerosis, arthritis, obesity and diabetes (Yu et al. 2016). In particular, phytoestrogens function as antioxidants and may be superior to vitamins C and E (Sierens et al. 2001). Just two servings of soy foods can increase blood flow in heart vessels and improve the health of heart muscle. Phytoestrogens also widen blood vessels, reduce blood pressure, decrease blood cholesterol levels and prevent atherosclerosis in blood vessels (Rietjens, Louisse & Beekmann 2017). Note, however, that these plant hormones can suppress the human immune system, which could pose risks (Masilamani, Wei & Sampson 2012).

Diabetic patients can benefit from consuming plant estrogens. Studies performed in the U.S. and Asia have found an inverse association between consumption of a large variety of soy products and risk of type 2 diabetes (Li et al. 2018). Genistein normalizes glucose parameters in peripheral blood, indicating that this isoflavone may increase insulin levels.

Plant Estrogens for Postmenopausal Women

Researchers have found that supplementing diets with 30 mg of genistein daily can suppress osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. That dosage mirrors the regular intake of isoflavones in the traditional Eastern diet. Moreover, several studies suggest that isoflavones may reduce hot flashes and other postmenopausal symptoms (Messina 2014).

Societies with high consumption of soy foods or isoflavones also see a lower prevalence of breast cancer and other hormone-regulated cancers (Rietjens, Louisse & Beekmann 2017). Epidemiologists have noted a reduction in postmenopausal breast cancer even in women consuming moderate amounts of soy (Anderson et al. 2013). Phytoestrogen consumption before menopause has also been linked with protection against breast cancer (Lee et al. 2009). In clinical studies, patients diagnosed with breast tumors who proceeded with soy intake had a lower rate of recurrence than patients without soy in their diet. Further, soy food intake has been found to strengthen existing anti-tumor therapies, such as tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitors (Kang et al. 2010). Phytoestrogens provide better protection if they are consumed during the teen years or earlier in childhood (Badger et al. 2002; Korde et al. 2009), and there’s some suggestion that consuming soy formula may have a preventive effect against breast tumors (Boucher et al. 2008), though more research is needed.

The accumulated data raise the question of whether phytoestrogens could be used for prevention and supplementary therapy of hormone-regulated malignancies. However, some studies have reported an increase in abnormal growth of breast tissue after short-term intake of isoflavones (Rice & Whitehead 2006). Thus, the benefits of soy in women’s diets must be weighed against its potential risks.

See also: Plant-Based Foods Curb Chronic Disease

Phytoestrogens for Skin Health

Phytoestrogens can also influence the health of the skin. For instance, acne results when overproduction of testosterone activates the sebaceous glands. Since isoflavones decrease testosterone’s effects, teenagers worrying about acne might consider adding soy foods to their diet.

Natural aging of facial skin reduces elasticity and moisture, leading to wrinkles. Consuming isoflavones can reduce these age-mediated skin changes. One study found that daily consumption of 40 mg of aglycone, a phytoestrogen, improved wrinkles and skin plasticity in middle-aged women (Izumi et al. 2007). And equol, a phytoestrogen in white cabbage, was shown to decrease facial wrinkles when taken as a dietary supplement (Oyama et al. 2012).

The gamut of potential anti-aging actions of phytoestrogens on the skin includes antioxidative effects, stimulation of collagen and elastin, growth of blood vessels, and increased skin repair and regeneration (Irrera et al. 2017). Furthermore, androgen-dependent baldness may potentially be prevented or at least slowed by isoflavones (McElwee et al. 2003).

Phytoestrogens and Men’s Health

Phytoestrogens also improve men’s health in several ways. Consider the impact on prostate cancer, the second-leading cause of cancer deaths in U.S. men. Notably, Asian populations with a high intake of soy are less affected by prostate cancer. Moreover, multiple studies in Asia, the U.S. and Europe have found that regular consumption of soy products decreases the risk of prostate cancer (Applegate et al. 2018). Intake of isoflavones extracted from red clover has been linked to prostate cancer cell death by the process known as apoptosis (Reiter, Gerster & Jungbauer 2011).

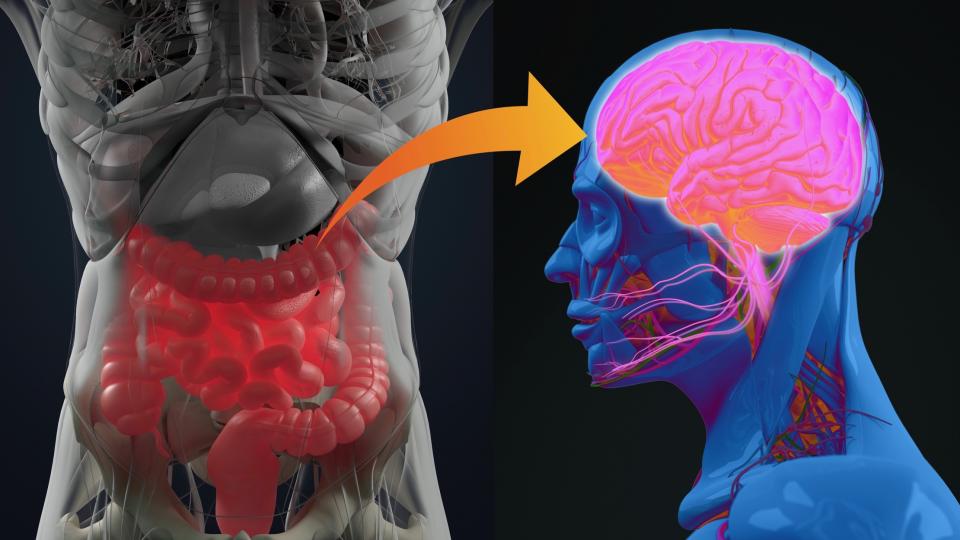

Cognitive and Mental Health Effects

Phytoestrogens often seem to mimic the physiological health effects of estrogens. Just as estrogens are known to improve cognitive functions in women, phytoestrogens have been shown to assist healthy aging by retaining cognitive performance. Daily food supplementation with 200 mg of resveratrol, a phytoestrogen in grapes and peanuts, improved memory, reasoning and problem-solving in postmenopausal women, according to Australian researchers (Thaung Zaw, Howe & Wong 2017).

Equol, the isoflavone in white cabbage, significantly improves cognitive capacities in elderly individuals (Igase et al. 2017). Scientists believe that phytoestrogens stimulate cognitive performance by elevating blood flow in the brain (Evans, Howe & Wong 2017).

Depression may be another therapeutic target for dietary estrogens. Interestingly, the risk of developing depression is higher in women than in men, which implicates sexual hormones in this process. With regard to menopause, depression is a rather early feature, occurring even sooner than hot flashes. Phytoestrogens may be able to mend the symptoms of depression, since the chemical structure of soy-derived isoflavones is quite similar to the structure of synthetic drugs used to treat depressive disorders.

To evaluate the potential benefits of plant estrogens, clinicians from the Americas, Asia and Europe have performed more than 20 clinical trials in which patients with depression received different doses of isoflavone supplements. Overall, many of those studies have shown a significant decline in depressive symptoms. Moreover, isoflavones build on the effects of antidepressants by improving the emotional state of patients.

Is Soy Safe for Children?

Is it natural and healthy to feed soymilk to infants? Pediatricians worry that the estrogenic activity of phytoestrogens may affect child development. Infant formula containing soy was introduced in the U.S. in 1909. At that time, soy formula was suggested as a substitute for children who could not tolerate cow’s milk. Nowadays, normal infant formula can be replaced by soy-based formula in cases of allergies, inability to digest milk or when parents want to avoid feeding animal milk to their children.

Soy formula is rich in isoflavones, with about 40 mg of plant estrogens per liter. In contrast, isoflavone concentration in human breast milk is only about 5 micrograms per liter (Setchell et al. 1998). Infants who regularly drink soy formula are consuming approximately 10 times more isoflavones than adults on a high-soy diet (Badger et al. 2002; Mortensen et al. 2009).

Though no particular health disturbances have been documented in infants consuming soymilk, according to the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS 2018), toddlers may be more susceptible to estrogens than grownups are. Pediatricians are mainly concerned about the potential effects of phytoestrogens on cognitive and sexual development, immunity, and endocrine organs. However, numerous epidemiological studies have found no significant evidence of developmental, reproductive or endocrine disorders associated with soy formula intake (Vandenplas et al. 2014).

Epidemiological studies have not confirmed a hypothesis about early puberty in children fed with soy formula. Studies on neurological development generated similar results: Teenagers showed no differences in behavior, learning capacities or emotional status whether they were fed soy formula or breastfed when they were infants.

See also: Adults Can Play a Leading Roll in Children’s Eating Habits

Precautions: Clouds on the Horizon

No matter how promising some recent studies may sound, scientists admonish dietitians and medical doctors not to recklessly prescribe isoflavone supplementation. The potential effects of plant hormones on male and female reproductive systems are not fully understood (Bennetau-Pelissero 2016). Excessive soy

intake may cause an imbalance in the menstrual cycle, and several studies have associated decreased sperm count and erectile dysfunction with high intake of soy products.

Furthermore, phytoestrogens may also influence other endocrine systems—inhibiting the effects of thyroid hormones, in particular. Soy protein is also one of the main triggers of food allergies.

What’s Next for Phytoestrogens

Many scientists agree that the data on health benefits of soy-derived isoflavones suggest potential preventive and therapeutic applications. However, what’s the next step?

One obvious path would be to determine which populations might best profit from isoflavone supplementation. For instance, communities with a high frequency of lactose intolerance could be target groups for including soy-derived products in the regular diet. Detailed knowledge of the family history of specific disorders might influence decisions on whether to recommend soy formula in every case. And with regard to soy food production, new processing methods might be required to create foods with a higher phytoestrogen content.

One more thing to remember: Despite all the healthy optimism in the scientific community, phytoestrogens should be valued and used with caution. More studies are needed before we can solve the puzzle of phytoestrogens.

WHAT IS A PHYTOESTROGEN?

Phytoestrogens are chemical compounds common in soy-based foods. Their chemical structure is similar to that of estrogen, the mammalian sex hormone.

Phytoestrogens have been linked to a host of health benefits. Among them:

- reduced risk of breast and prostate cancer

- easing of osteoporosis and menopausal symptoms

- improved cognitive function

- healthier skin with fewer wrinkles

Risks of phytoestrogens include the following:

- potential declines of immune function

- infertility and erectile dysfunction in men

References

Anderson, L.N., et al. 2013. Phytoestrogen intake from foods, during adolescence and adulthood, and risk of breast cancer by estrogen and progesterone receptor tumor subgroup among Ontario women. International Journal of Cancer, 132 (7), 1683–92.

Applegate, C.C., et al. 2018. Soy consumption and the risk of prostate cancer: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients, 10 (1), E40.

Badger, T.M., et al. 2002. The health consequences of early soy consumption. The Journal of Nutrition, 132 (3), 559S–65S.

Bennetau-Pelissero, C. 2016. Risks and benefits of phytoestrogens: Where are we now? Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care, 19 (6), 477–83.

Boucher, B.A., et al. 2008. Soy formula and breast cancer risk. Epidemiology, 19 (1), 165–66.

Eisenbrand, G. 2007. Isoflavones as phytoestrogens in food supplements and dietary foods for special medical purposes. Opinion of the Senate Commission on Food Safety (SKLM) of the German Research Foundation (DFG)-(shortened version). Molecular Nutrition & Food Research, 51 (10), 1305–12.

Evans, H.M., Howe, P.R.C., & Wong, R.H.X. 2017. Effects of resveratrol on cognitive performance, mood and cerebrovascular function in post-menopausal women; a 14-week randomised placebo-controlled intervention trial. Nutrients, 9 (1).

Igase, M., et al. 2017. Cross-sectional study of equol producer status and cognitive impairment in older adults. Geriatrics & Gerontology International, 17 (11), 2103–8.

Irrera, N., et al. 2017. Dietary management of skin health: The role of genistein. Nutrients, 9 (6).

Izumi, T., et al. 2007. Oral intake of soy isoflavone aglycone improves the aged skin of adult women.

Kang, X., et al. 2010. Effect of soy isoflavones on breast cancer recurrence and death for patients receiving adjuvant endocrine therapy. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 182 (17), 1857–62.

Korde, L.A., et al. 2009. Childhood soy intake and breast cancer risk in Asian American women. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, 18 (4), 1050–59.

Lee, S.A., et al. 2009. Adolescent and adult soy food intake and breast cancer risk: Results from the Shanghai Women’s Health Study. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 89 (6), 1920–26.

Li, W., et al. 2018. Soy and the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice, 137, 190–99.

Masilamani, M., Wei, J., & Sampson, H.A. 2012. Immunologic Research, 54 (1–3), 95–110.

McElwee, K.J., et al. 2003. Dietary soy oil content and soy-derived phytoestrogen genistein increase resistance to alopecia areata onset in C3H/HeJ mice. Experimental Dermatology, 12 (1), 30–36.

Messina, M. 2014. Soy foods, isoflavones, and the health of postmenopausal women. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 100 (1 Suppl.), 423S–30S.

Mortensen, A., et al. 2009. Analytical and compositional aspects of isoflavones in food and their biological effects. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research, 53 (Suppl. 2), S266–309.

NIEHS (National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences). 2018. Soy infant formula. Accessed July 9: niehs.nih.gov/health/topics/agents/sya-soy-formula/index.cfm.

Oyama, A., et al. 2012. The effects of natural S-equol supplementation on skin aging in postmenopausal women: A pilot randomized placebo-controlled trial. Menopause, 19 (2), 202–10.

Reiter, E., Gerster, P., & Jungbauer, A. 2011. Red clover and soy isoflavones—an in vitro safety assessment. Gynecological Endocrinogy, 27 (12), 1037–42.

Rice, S., & Whitehead, S.A. 2006. Phytoestrogens and breast cancer—promoters or protectors? Endocrine-Related Cancer, 13 (4), 995–1015.

Rietjens, I., Louisse, J., & Beekmann, K. 2017. The potential health effects of dietary phytoestrogens. British Journal of Pharmacology, 174 (11), 1263–80.

Setchell, K.D., et al. 1998. Isoflavone content of infant formulas and the metabolic fate of these phytoestrogens in early life. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 68 (6), 1453S–61S.

Sierens, J., et al. 2001. Effect of phytoestrogen and antioxidant supplementation on oxidative DNA damage assessed using the comet assay. Mutation Research, 485 (2), 169–76.

Thaung Zaw, J.J., Howe, P.R.C., & Wong, R.H.X. 2017. Does phytoestrogen supplementation improve cognition in humans? A systematic review. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1403 (1), 150–63.

Vandenplas, Y., et al. 2014. Safety of soya-based infant formulas in children. British Journal of Nutrition, 111 (8), 1340–60.

Yu, J., et al. 2016. Isoflavones: Anti-inflammatory benefit and possible caveats. Nutrients, 8 (6), E361.

Zaheer, K., & Humayoun Akhtar, M. 2017. An updated review of dietary isoflavones: Nutrition, processing, bioavailability and impacts on human health. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 57 (6), 1280–93.