Analyze Today’s Hot Button Issues in Nutrition

When opinions, beliefs and science collide, emotions can heat up around nutrition debates. Cool down the conversation by balancing opinions with facts.

Nutrition has become an international pastime. It’s woven into conversations among friends in person and online; it is a priority for scientific study and public policy; diet-related headlines make local and international news; and celebs leverage their fame to promote their products and practices in the kitchen. Accompanying this enthusiasm are differing opinions, scientific debates and downright disputes. Meanwhile, misinformation fills gaps left by insufficient research or inconclusive results. Add in the misinterpretation of research by the media plus anecdotal guidance from self-proclaimed experts, and consumers are left confused.

Answering client questions and determining the most relevant recommendations can be overwhelming (and time-consuming). The list of hot button nutrition topics being debated is boundless and ever-changing. Three debates involve carbohydrates, fats and milk. With an understanding of each issue, along with the light shed by a snapshot of current scientific evidence, you can relay relevant messages to your clients—using expert tips for explaining the difference between science and opinion.

Hot Button Debate: Half-Carb, Low-Carb or No-Carb Diets

One could say that carbohydrates, or “carbs,” are quite complex (pun intended). Should carbs be the primary source of fuel in our diets, or should they be limited or even avoided to improve overall health and/or weight management? Recommendations evolve and can be inconsistent among public health officials, healthcare professionals, the health media and consumers.

SCAN THE ARGUMENTS

Public health messages focus on limiting added sugars and choosing whole grains. The 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans advise consumers to make whole grains half of the grains they eat (HHS & DOA 2015). The Recommended Dietary Allowance for carbohydrates of any kind is 130 grams per day (IOM 2006). Neither guideline recommends a high fat intake.

Healthcare professionals maintain a similar stance. The American Heart Association’s 2016 scientific statement on dietary patterns emphasizes limiting added sugars and says that most grain servings should be whole—not refined (Van Horn et al. 2016). For sport, the position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, Dietitians of Canada, and the American College of Sports Medicine maintains that athletes need carbs, with precise amounts dependent on exercise type, duration and intensity, along with individualized factors (Thomas, Erdman & Burke 2016). None of these organizations warn against consuming carbohydrates, nor do they promote a high fat intake.

Now consider the health media and consumer trends, which fall on the side of the “low-carb diet.” For example, according to the seventh annual “What’s Trending in Nutrition” survey (see “Mind the Trends,” below), registered dietitians report that the top diet among consumers for 2019 is the ketogenic diet, which features low or no carbohydrates. The objective of the ketogenic plan is to reduce carbs so that the body needs to convert fat into fuel for the brain and central nervous system. Another popular low-carb diet that has endured over the past several years is the paleo diet. While this plan has a variety of interpretations, a consistent feature is elimination of grains, dairy and legumes.

Anecdotal evidence or testimonials that support low-carb eating are also found in social and traditional media. Keto recipes, low-carb eating tips, beginners’ guides, before-and-after pictures, and personal stories provide rationale for reducing carbohydrate intake.

While it’s unlikely that everyone will agree—eat carbs or don’t—the legitimacy of reevaluating carbohydrate intake has gained ground (Choi 2019). When the advisory committee working on the next edition of the Dietary Guidelines for Americans meets, a low-carb diet will be discussed.

REVIEW THE SCIENCE

Peer-reviewed studies have explored the benefits and pitfalls of low-carb eating for weight management and the risk factors for metabolic and cardiovascular diseases. Overall, messages are mixed.

Several randomized clinical trials have shown healthy associations between a low-carb diet and lipid profiles; others have found ill effects on low-density lipoprotein (“bad”) cholesterol or other markers of cardiovascular health. Substantially reducing carbohydrate intake has seemed to help manage blood glucose or reduce the risk of diabetes, and the data supports these benefits. For weight loss, the evidence shows that a low-carb diet typically induces weight loss, sometimes described as rapid, but in the long run, it’s net-neutral compared with other calorie-restricted diets.

Here’s a sampling of the mixed results:

Pro low-carb. In a randomized, controlled trial, researchers determined that a very low-carbohydrate diet was more effective for short-term weight loss than a low-fat diet and, after 6 months, was not associated with adverse effects on important cardiovascular risk factors in healthy women (Brehm et al. 2003).

Pro carb. A 12-month weight loss study published in JAMA found no difference in weight change or metabolic outcomes between a healthy low-fat diet and a healthy low-carbohydrate diet. Thus, neither plan was deemed better than the other (Gardner et al. 2018).

Pro low-carb. A randomized clinical trial compared the effects of a very low-carbohydrate diet, which was high in unsaturated fat and low in saturated fat, with those of a high-carbohydrate, low-fat diet on glycemic control and cardiovascular disease risk factors in people with type 2 diabetes. In 12 months, both diets led to substantial weight loss and glycemic improvements. The very low-carb diet achieved greater improvements in lipid profiles and blood glucose stability and greater reductions in diabetes medication requirements (Tay et al. 2015).

Pro carb. Researchers found that consuming a reported low-carb diet with high amounts of protein and fat had a negative impact on arterial wall function in patients with increased CVD risk (Merino et al. 2013).

Pro low-carb. A 2-year dietary intervention trial with moderately obese individuals compared the effects of a low-fat diet, a Mediterranean diet and a low-carb diet (20 g of carbohydrates per day). Both the Mediterranean and the low-carb diet proved to be effective for weight loss; they also showed better metabolic benefits than the low-fat diet (Shai et al. 2008).

Unsure. A meta-analysis published in the British Journal of Nutrition found that a low-carb diet (versus a low-fat diet) was significantly associated with two important cardiovascular risk factors: greater weight loss (on the positive side) and increased LDL cholesterol (on the negative side). The authors raised concern that the beneficial changes from a low-carb diet must be weighed against this potential increase in LDL cholesterol (Mansoor et al. 2016).

BALANCE THE CONTRADICTIONS

To sum it up, a review published in the European Journal of Nutrition in 2018 provides an overview of where to go with the carb conversation (Brouns 2018):

- There is lack of data supporting the long-term efficacy, safety and health benefits of low-carb, high-fat diets. Recommendations should take this into account.

- Lifestyle interventions in people at high risk of developing type 2 diabetes blunt the progression of the disease—even in those consuming a carb-rich diet.

- People appear to have difficulty maintaining a ketogenic diet. It may be more practical to consider a nonketogenic diet supplying 100–150 g of carbohydrate per day.

Bottom line: Any type of diet that reduces energy (calorie) intake will result in weight loss and favorable metabolic and functional changes.

See also: Carbohydrate Controversy: “Good” Sugars vs. “Bad” Sugars?

Hot Button Debate: Saturated Fat and Heart Disease

Since the 1960s, the American Heart Association (and, later, the U.S. government) had been warning unequivocally against consuming saturated fat (e.g., dairy products and some meats) because of the risk to heart health. Then, in 2014, the book The Big Fat Surprise (Simon & Schuster 2014) threw this argument into question. Author Nina Teicholz appeared to debunk the 60-year-old recommendations for fat, including the saturated type. In media coverage, she ignited debate with comments like, “Don’t believe the American Heart Association . . .” and “fat has been misunderstood and unfairly vilified.”

The media jumped on board with headlines: “Eat butter. Scientists labeled fat the enemy. Why they were wrong.” (Time, June 12, 2014), “The Questionable Link Between Saturated Fat and Heart Disease” (The Wall Street Journal, May 6, 2014) and “The Big Fat Lie We’ve Been Fed About Our Diet” (The Fiscal Times, May 22, 2014). The fervor hasn’t subsided. Just this year, a website published an article called “The Big Fat Lie: How the Government Caused the Obesity Crisis”(71Republic.com, January 22, 2019).

Was the pro-fat argument a ruse in support of butter? Actually, no.

REVIEW THE SCIENCE

In 2010, Ronald M. Krauss, director of atherosclerosis research at Children’s Hospital Oakland Research Institute, and his team determined that, based on the body of evidence, the effect of a reduction in saturated fat intake must be evaluated in the context of which macronutrients replace the saturated fat. They suggested that, by itself, saturated fat is not a predictor of CVD. Rather, the key to reducing cardiovascular risk factors is to minimize refined carbohydrate intake and reduce body fat (Siri-Tarino et al. 2010).

Soon after (in 2014), a systematic review and meta-analysis of 32 observational studies of fatty acids from dietary intake, 17 observational studies of fatty acid biomarkers, and 27 randomized, controlled trials of fatty acid supplementation concluded that there was no association between fatty acid type and coronary risk (Chowdhury et al. 2014). Basically, the authors said there was no basis for the current recommendations.

The American Heart Association released a white paper in June 2015 describing the evolution of the association’s dietary fat recommendations and defending the evidence. The authors contended that saturated fat should be limited, noting, “Many of the claims that question recommendations to reduce dietary saturated fats rely on analyses that have not taken the replacement nutrient into consideration. When dietary saturated fat is decreased, another dietary component is increased.” They added that “replacement of dietary saturated fat with polyunsaturated fat has been shown to have a beneficial effect on coronary heart disease risk and LDL cholesterol concentrations. Replacement of dietary saturated fat with carbohydrate has been shown to have lesser effect” (AHA 2015). These statements align with the AHA’s current recommendations.

FOR EGGS, IT’S NEVER OVER EASY

The truth about eggs and heart health, warns Dr. Oz, is that eggs (or at least egg yolks) are bad for you (Oz & Roizen 2019). This is one of several alarmist responses to the recent analysis of six prospective studies using a statistical model to estimate the risk of CVD occurrence and death (Zhong et al. 2019). The research review’s final conclusion was that “among US adults, higher consumption of dietary cholesterol or eggs was significantly associated with higher risk of incident CVD and all-cause mortality in a dose-response manner.”

Not so fast. The review authors also stated that “the associations between egg consumption and incident CVD . . . were no longer significant after adjusting for dietary cholesterol consumption.” Moreover, when the authors looked more closely, intake of dietary cholesterol (as found in meat, eggs, dairy, fish and poultry) was more strongly linked with risk of stroke than with heart disease, and it was associated with both CVD and non-CVD deaths.

Bottom line: It’s important to read study details carefully—because now, claims about this study’s findings are out there, confusing consumers, and you can’t unscramble an egg.

WHOLE-FAT AND LOW-FAT DAIRY

Researchers have been exploring possible risks from fatty acids in dairy, given that these are saturated fat. A recent multinational Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) cohort study ran from 2003 to 2018 and included data from 136,684 individuals (Dehghan et al. 2018). The researchers examined the associations between total dairy intake and consumption of specific dairy products (milk, cheese and yogurt), on the one hand, and cardiovascular disease and mortality (over a median follow-up period of 9.1 years), on the other. Dairy products were divided into whole-fat and low-fat categories. Here’s what the results showed:

- Higher intake of total dairy (>2 servings per day compared with no intake) was associated with lower risk of cardiovascular mortality, major CVD, stroke and all types of cardiovascular events overall. No significant association with myocardial infarction was observed.

- Higher intake (>1 serving versus no intake) of milk and yogurt was associated with lower risk of all types of cardiovascular events overall.

- Cheese intake was not significantly associated with all types of cardiovascular events overall.

- Butter intake was low and was not significantly associated with clinical outcomes.

Bottom line: The authors concluded that dairy consumption was associated with lower risk of mortality and major CVD events in a diverse multinational cohort.

BALANCE THE CONTRADICTIONS

For 5 years, the “big fat surprise” has maintained modest momentum in the media. The surprise Teicholz described has been refuted by some, but, overall, the needle has moved. Scientists continue to investigate the relationship between saturated fat and heart disease, as well as the importance of choosing replacement nutrients wisely.

Public health experts have adjusted their language to soften the advice against saturated fat in the diet. For example, an article from Harvard Health Publishing referred to saturated fat as the “in-between fat” (HHP 2018). The authors explained, “A handful of recent reports have muddied the link between saturated fat and heart disease. One meta-analysis of 21 studies said that there was not enough evidence to conclude that saturated fat increases the risk of heart disease, but that replacing saturated fat with polyunsaturated fat may indeed reduce risk of heart disease.”

The American Heart Association maintains that saturated fat from all sources should be limited or replaced with unsaturated fat sources, not refined carbohydrates (AHA 2015). They recommend aiming for a dietary pattern that derives just 5%–6% of its calories from saturated fat. When it comes to dairy, the AHA suggests consuming no- or low-fat products.

See also: Is “Bad” Fat Now “Good”?

Hot Button Debate: Cow’s Milk Versus Plant Milk

The conversational volume surrounding milk from cows versus milk from plants has reached a crescendo. The Food and Drug Administration is examining the standard of identity required to use the term milk. Through comments and arguments, both dairy producers and plant-based camps are pushing the FDA to take a stand: Can plant-derived milk be called “milk”? Is milk only from a cow? What about a goat? Or a nut? As of now, it’s not been decided (Watson 2018).

SCAN THE ARGUMENTS

Perception is playing a big role in consumer choices. A market study on dairy- and plant-based milk with data from 2,010 respondents showed that dairy-based milk and plant-based alternatives are purchased with nutrition in mind, yet many consumers are not aware of the nutritional distinctions between products (DMI 2018). Almond milk, soy milk and coconut milk are perceived as having the same or greater amounts of vitamins, protein or other key nutrients compared with dairy milk; the majority of adults believe that the nutritional content is the same in these products.

Interestingly, nearly half of respondents (41%) purchased both dairy- and plant-based milk in the 6 months before the survey.

Consumers hold plant-based protein in high regard. Over 70% of adults (80% of those ages 1–34 years) agree that plant-based proteins are healthy; close to half say plant-based proteins are better for you than animal-based proteins (Mintel Group 2018).

The stakes are high for both dairy- and plant-based milk producers. The U.S. market for dairy milk has seen a drop in recent years–down 7% in 2015 and projected to decline an additional 11% through 2020. Meanwhile, plant-based offerings were up 9% in 2015 (Mintel Group 2016).

BALANCE THE CONTRADICTIONS

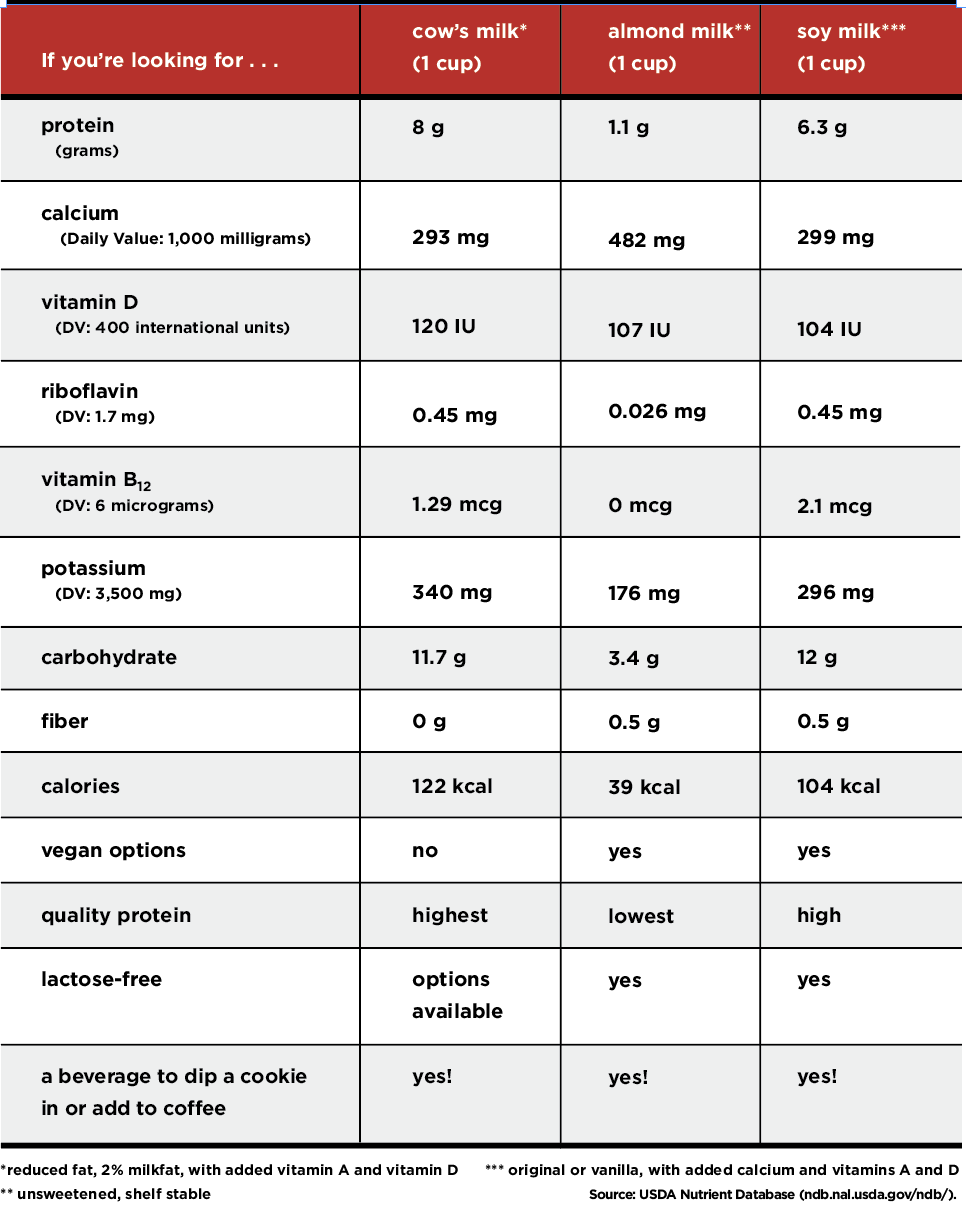

It doesn’t have to be a competition in your refrigerator. Both cow’s milk and plant-based milks have attributes. Consumers may not be aware of the differences among varieties of milk, but the chart below shows that both provide the same nutrients, only in different quantities.

See also: The New Dairy Queens

Nutrition Debates and Dilemmas

Nutrition is perfectly positioned for misinterpretation. Dietary intake assessment is error-prone and difficult to conduct reliably. Science itself is a progression, not a conclusion. Media needs to hook you with shocking headlines, not statements like, “Research shows that something may do something sometimes.”

Consumers wanting to improve their lives seek answers to questions and solutions to problems. All of this leads to discourse, confusion and even frustration. As a fitness professional, you already know it’s imperative to create messages that resonate with your clients. To be heard, balance the science and evidence with today’s trends: Meet your clients where they are, be open-minded, listen well and provide your best understanding of the issue.

Mind the Trends

To get a read on what registered dietitians are hearing from consumers, Pollock Communications and Today’s Dietitian 2019 conduct an annual survey of “What’s Trending in Nutrition.” Each year, around 1,500 RDs predict purchase drivers, healthy-food perceptions, popular diets, and influences on consumer decisions. Understanding what consumers are thinking and choosing will help you develop messages that make sense to them. See the survey’s “Top 10 Superfoods for 2019” at todaysdietitian.com/news/122018_news.shtml.

Addressing Hot Button Issues With Clients

Answering questions on hot button topics can be difficult. Here’s what registered dietitians answered when asked, “How do you handle questions about divisive nutrition issues? How do you balance the science with your opinion/belief?”

“I recognize that there can be deep emotional connections to the choices people make. I think it’s important to validate the choice or the point of view, then work to engage the audience (consumer, reader, listener) to use their critical thinking skills.

I try to provide the facts as objectively as possible and then perhaps [give] some pros or cons (using visuals can sometimes help: graphs, tables, photos, infographics, etc.). We all have confirmation bias. I distinguish the scientific facts from my opinions with statements like ‘in my opinion’ versus ‘the science says.’”

—Rosanne Rust, MS, RDN, LDN, nutrition writer and blogger at Chew the Facts

“It’s important to first know [clients’] intentions with their question and what information they already have about the topic. If my clients feel strongly about their view, I provide a review of the current science. Right or wrong, registered dietitians can have different philosophies. I always try to merge science with reality and consider the characteristics of whom I’m speaking to. I want to provide guidance that fits in their lifestyle, not just the science.”

—Kelly Jones, MS, RD, CSSD, LDN, nutrition consultant and board-certified specialist in sports dietetics

“I outline the issue from several perspectives by citing facts supported by scientific references. For me, it is a best practice to make a pro/con list. I tend to leave my opinion/belief out of the equation. It isn’t about me . . . it’s about my client and what the evidence shows.”

—Lisa Jones, MA, RDN, LDN, FAND, nutrition consultant

“One of the most important things is to look at the overall body of evidence. Do not rely on one study to make a decision on an issue. I also encourage people to be careful of how [they] interpret data. Try not to only support the science that agrees with or proves your position.”

—Sharon Palmer, MS, RDN, author of The Plant-Powered Diet (The Experiment 2012)

“Ideally, I start with something nonthreatening and nonconfrontational like, ‘A lot of people have that concern’ or, ‘That’s a good question.’ Then I answer the question and provide a rationale for my answer. I try to cite research or recommendations from authoritative organizations. For some issues, I may explain that the preponderance of the evidence suggests this now and [that] we’ll have to see what new science brings. I point out the safe path until we have more conclusive evidence.”

—Jill Weisenberger, MS, RDN, CDE, CHWC, FAND, author of Prediabetes: A Complete Guide (American Diabetes Association 2018)

“Typically, I try to cite a quality research article or refer to the information posted on a .gov or .edu website. I always add a disclaimer to suggest that each individual is different and not everything will work for everyone. It’s difficult sometimes to stay open to opinions that directly oppose my own, but nutrition is an ever-evolving science. We all need to keep in mind that something that sounds outrageous now may be the new normal in a decade.”

—Lauren Harris-Pincus, MS, RDN, founder of NutritionStarringYOU.com, author of The Protein-Packed Breakfast Club (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform 2017)

References

AHA (American Heart Association). 2015. Saturated fat. Accessed Mar. 29, 2019: heart.org/en/healthy-living/healthy-eating/eat-smart/fats/saturated-fats.

Brehm, B.J., et al. 2003. A randomized trial comparing a very low carbohydrate diet and a calorie-restricted low fat diet on body weight and cardiovascular risk factors in healthy women. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 88 (4), 1617–23.

Brouns, F. 2018. Overweight and diabetes prevention: Is a low-carbohydrate-high-fat diet recommendable? European Journal of Nutrition, 57 (4), 1301–12.

Choi, C. 2019. US experts reviewing low-carb, other diets for guidelines. Associated Press. Accessed Apr. 4, 2019: apnews.com/2e2dea138ed14570a137a8331ab925e6.

Chowdhury, R., et al. 2014. Association of dietary, circulating, and supplement fatty acids with coronary risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Internal Medicine, 160 (6), 398–406.

Dehghan, M., et al. 2018. Association of dairy intake with cardiovascular disease and mortality in 21 countries from five continents (PURE): A prospective cohort study. The Lancet, 392 (10161), 2288–97.

DMI (Dairy Management Inc.). 2018. Consumer perceptions, dairy and plant-based milk alternatives. Accessed Apr. 18, 2019: usdairy.com/~/media/usd/public/dairy-and-plant-based-beverages-research.pdf.

Gardner, C.D., et al. 2018. Effect of low-fat vs low-carbohydrate diet on 12-month weight loss in overweight adults and the association with genotype pattern or insulin secretion: The DIETFITS randomized clinical trial. JAMA, 319 (7), 667–79.

HHP (Harvard Health Publishing). 2018. The truth about fats: The good, the bad, and the in-between. Accessed Apr. 1, 2019: health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/the-truth-about-fats-bad-and-good.

HHS & DOA (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture). 2015. 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 8th ed. Accessed Apr. 5, 2019: health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2006. Dietary Reference Intakes: The Essential Guide to Nutrient Requirements. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press.

Mansoor, N., et al. 2016. Effects of low-carbohydrate diets v. low-fat diets on body weight and cardiovascular risk factors: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. British Journal of Nutrition, 115 (3), 466–79.

Merino, J., et al. 2013. Negative effect of a low-carbohydrate, high-protein, high-fat diet on small peripheral artery reactivity in patients with increased cardiovascular risk. British Journal of Nutrition, 109 (7), 1241–47.

Mintel Group. 2016. US sales of dairy milk turn sour as non-dairy milk sales grow 9% in 2015. Accessed Mar. 23, 2019: https://www.mintel.com/press-centre/food-and-drink/us-sales-of-dairy-milk-turn-sour-as-non-dairy-milk-sales-grow-9-in-2015.

Mintel Group. 2018. Better for you eating trends—US—August 2018. London: Mintel Group.

Oz, M., & Roizen, M. 2019. The truth about eggs and heart health. NewsMax Health. Accessed Apr. 4, 2019: newsmax.com/health/dr-oz/eggs-cholesterol-cardiovascular-disease-dr-oz/2019/04/04/id/910184/.

Shai, I., et al. 2008. Weight loss with a low-carbohydrate, Mediterranean, or low-fat diet. New England Journal of Medicine, 359 (20), 229–41.

Siri-Tarino, P.W., et al. 2010. Saturated fat, carbohydrate, and cardiovascular disease. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 91 (3), 502–9.

Tay, J., et al. 2015. Comparison of low- and high-carbohydrate diets for type 2 diabetes management: A randomized trial. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 102 (4), 780–90.

Thomas, D.T., Erdman, K.A., & Burke, L.M. 2016. Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, Dietitians of Canada, and the American College of Sports Medicine: Nutrition and athletic performance. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 116 (3), 501–28.

Today’s Dietitian. 2019. Annual survey reveals food trends among consumers and RDs. Accessed Mar. 26, 2019: todaysdietitian.com/news/122018_news.shtml.

Van Horn L., et al. 2016. Recommended dietary pattern to achieve adherence to the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology (AHA/ACC) Guidelines: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 134 (22), e505–29.

Watson, E. 2018. Plant-based ÔÇÿmilk’ row heats up as FDA commissioner says ÔÇÿpublic health concerns’ inform the agency’s renewed interest in dairy standards of identity. FoodNavigator-USA. Accessed Mar. 23, 2019: foodnavigator-usa.com/Article/2018/07/26/Plant-based-milk-row-heats-up-as-FDA-probes-dairy-standards-of-identity?utm_source=copyright&utm_medium=OnSite&utm_campaign=copyright.

Zhong, V.W., et al. 2019. Associations of dietary cholesterol or egg consumption with incident cardiovascular disease and mortality. JAMA, 321 (11), 1081–95.

Jenna A. Bell, PhD, RD

Jenna A. Bell, PhD, RD, holds a doctorate degree in exercise science and a master's degree in nutrition. She is a popular speaker and writer for IDEA Fitness Journal.