Understanding Set-Point Weight

Finding the right words to clearly explain the complicated science of weight loss and maintenance can be tricky. Use these ideas to educate clients—and yourself—on why lost pounds keep coming back.

Humans are hardwired to resist dietary restrictions. Science bears this out: In the absence of an ongoing weight maintenance program, half of the people who lose 10% or more of body weight gain it all back within 5 years or so (Montesi et al. 2016).

It used to be easy to blame this phenomenon on laziness or lack of dietary discipline. But that explanation isn’t persuasive anymore because of growing evidence that our bodies have a relentless drive to “correct” excessive weight loss and return to a “set-point” weight. Indeed, the science of set-point weight suggests we may need to shift our focus away from weight loss and toward healthier living and weight maintenance over time.

Fitness professionals can play a pivotal role in educating clients about set-point weight and its effect on wellness and weight loss. To make this happen, you must understand

- how the human body responds to dietary restrictions;

- why the body naturally reverts to a set-point weight; and

- how to convince clients to shift their perceptions on weight loss.

Educating yourself on set-point weight is the first step toward helping your clients escape the seemingly never-ending cycle of losing and regaining weight.

What Happens When We Diet

The persistence of the simplistic “eat less, move more” weight loss mantra is a nagging reminder of widespread misconceptions about the realities of set-point weight. Consider how much this advice exaggerates the ease of weight loss:

Supposedly, burning an extra 3,500 calories will trim 1 pound of body weight—potentially yielding a whopping 52-pound weight loss in a year. All it takes is a 500-calorie deficit every day—250 more calories of exercise and 250 fewer calories of food, for instance.

Yet somehow this math never seems to translate to real life. Sure, it may work at first. Consistent attention to creating a calorie deficit can make weight seem to peel away—especially over the first 6 months. But then something changes, no matter how well people stick to their new habits.

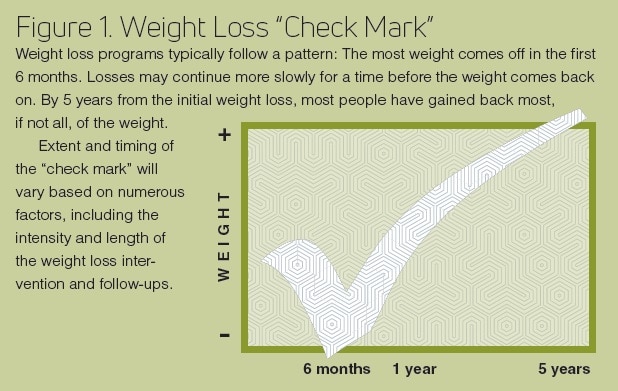

The weight starts to slowly (then not so slowly) creep back on. This creates the classic “weight loss check mark” (see Figure 1) we so often see in research studies and in our clients’ weight loss journeys.

We don’t know everything about set-point weight, but we do know that habitual under- or overfeeding triggers metabolic and hormonal changes that have a profound influence on dieters’ ability to keep weight off. When you understand how these mechanisms work, it will be easier to convey the concept to your clients, thus giving them a better chance to comprehend the realities of their lifelong weight loss and weight maintenance journey.

Why the Body Targets a Set-Point Weight

The human body naturally strives for a stable temperature of 98.6 degrees. Scientists now believe it does much the same with body weight. Once a person reaches a set-point weight—also called “customary” or “defended” weight—the body tweaks its metabolic rate to maintain that weight despite dietary fluctuations.

When we restrict calorie intake, the quest for set-point weight makes hunger rise and resting energy expenditure fall. That worked fine for early humans who faced long stretches of food scarcity. It’s less useful in our current era of food abundance and continual temptations to eat highly palatable salty, sugary and calorie-dense foods.

How strong is the drive for set-point weight? A research project targeted competitors in The Biggest Loser, studying them before weight loss, immediately afterward and then 6 years later. Their metabolic rates dramatically decreased and stayed that way even though the participants remained physically active (Fothergill et al. 2016). Other studies learned that hormonal changes that increase hunger and decrease metabolic rate persist even a year after weight loss (Sumithran et al. 2011).

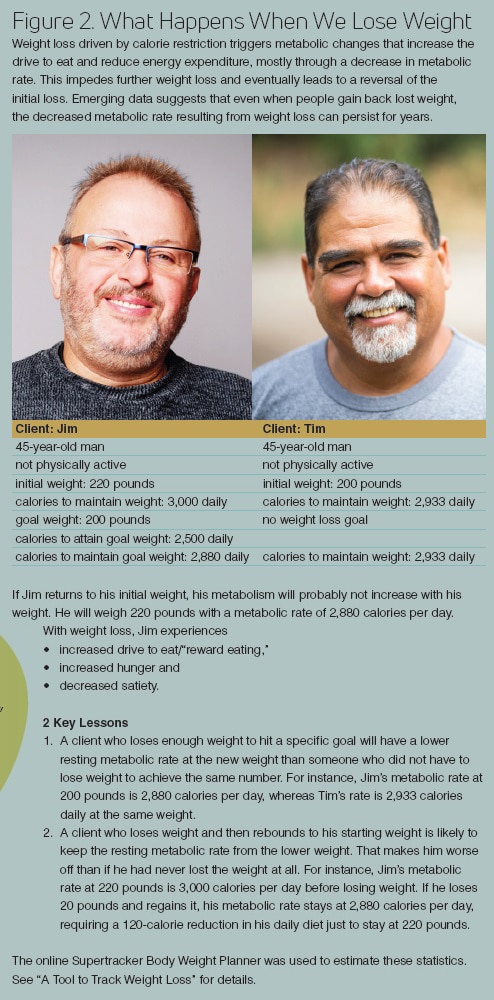

Ultimately, research shows that people who lose weight have a 3%–5% lower resting metabolic rate than their counterparts in control groups (Astrup et al. 1999). Scientists call this process adaptive thermogenesis, metabolic adaptation or enhanced metabolic efficiency (see Figure 2).

Educating Clients on Set-Point Weight

The facts on set-point weight can seem daunting or even depressing to clients who want to lose a lot of weight and keep it off. However, many of them may face graver long-term risks from rapidly losing and regaining weight repeatedly over their lifetimes. They’re probably better off focusing exclusively on a healthy lifestyle and letting the body find its set-point weight.

But how do we get clients to rethink the “eat less, move more” model they’ve been sold all their lives? Remember, adult learners are practical, goal-oriented and self-directed. They base learning on their life experience and the guidance most relevant to achieving their goals. They want to learn and are eager to integrate new knowledge into their daily lives (Knowles, Holton & Swanson 2011).

Use these tips to help clients understand the importance of set-point weight:

Explore Their Motivation for Weight Loss

What is fueling your clients’ weight loss efforts? A desire to be healthier? A need to improve function? Help people connect lifestyle change to indicators beyond weight. When possible, reframe a client’s motivation to focus on health and weight maintenance instead of weight loss.

You could say: “I know you are motivated to improve your health. A lot of studies show that with lifestyle changes, including better nutrition and more physical activity, health improves a lot, even with just small amounts of weight loss or just weight maintenance.”

Motivate With Achievable Goals

When a client wants to lose large amounts of weight, take the time to explore further and establish SMART goals—specific, measurable, attainable, relevant and time-bound. Avoid the temptation to fully endorse large weight loss goals.

If you must establish weight loss goals, aim for 1–2 pounds per week, emphasizing that the hardest part of the change is not losing weight; it’s keeping it off. Make sure clients understand what they’re up against.

Provide Examples of Success

Success stories can motivate clients, especially those who understand how the body resists losing lots of weight. Share success stories from other clients or more broadly from places like the National Weight Control Registry.

You could say: “It’s challenging, but many people have successfully lost weight and kept it off. Among nearly 3,000 participants in the National Weight Control Registry, about 87% were able to maintain a 10% weight loss for 5 and even 10 years. And we are learning more and more about how some people maintain weight loss.”

Explore Clients’ Weight Loss Experience

Ask clients about their attempts to lose weight. Did they return to a set-point weight? Where do they stand now relative to their starting weight?

You could say: “Please tell me a little bit about the ways you have tried to lose weight or improve your health in the past. What worked? What was challenging?”

Recognize Barriers

Help clients get mentally ready for common obstacles to long-term weight loss.

You could say: “When people lose weight, changes happen in the stomach and the brain that make it challenging to keep the weight off, despite full adherence to a weight loss plan.”

Or, “When your weight goes below your body’s ‘preferred weight,’ your brain tells you to eat more while releasing hormones that tell your metabolism to slow down. How might you plan for these changes?” For example, clients might focus on having filling, low—calorie, nutrient-dense foods like fruits and vegetables on hand and reducing access to highly processed, high-calorie, sugary foods.

Focus on Healthy Lifestyle and Prevention of Weight Gain

Clients can get healthier without weight loss. Help them identify steps that will improve health regardless of the effect on weight.

You could say: “What one or two actions could you do differently, starting today, to achieve your health goals?”

Admittedly, weight maintenance goals seem less exciting to clients than weight loss goals. But unlike weight loss objectives, maintenance goals are achievable and effective.

Praise Positive Changes

Acknowledge and affirm positive changes designed to boost health, especially those that improve nutrition and raise activity, regardless of whether weight loss happens. Help clients establish routines and habits to reinforce these improvements.

You could say: “This week, you planned to have breakfast every day, and you followed through with it. That shows a lot of commitment.”

Avoid Blame

When clients suffer setbacks or miss their goals, remind them that lapses and relapses are part of the journey, particularly when their metabolism is working against them.

If clients gain weight, you’ll have to troubleshoot for opportunities to reinforce the importance of lifestyle changes. Just remember that clients who stick to a weight loss maintenance plan after losing many pounds can still get heavier as the body tries to restore its set-point weight.

Use “People-First” Language

“People-first” language allows people to acknowledge a disease or condition without being defined by it. That means saying people have obesity or excess weight rather than saying they are obese or overweight people. Obesity carries so much stigma that it’s often advisable to avoid the word altogether and instead talk about excess weight or increased body mass index (or BMI).

Create Positive Exercise Experiences

Never waste an opportunity to prove to your clients that physical activity is fundamental to successful weight loss maintenance. When you’re creating positive activity experiences, you’re driving home the importance of combining diet and exercise to maintain weight loss.

Check for Understanding

When you’re educating clients about set-point weight, make sure you double back to ensure they understand what’s at stake.

You could say: “How do you think the body responds to weight loss? How will knowing this change your approach to losing weight?”

Dispel Myths

This goes for colleagues and clients: Dispel myths or misconceptions about weight loss and weight loss maintenance. In particular, help people understand that weight loss maintenance is not as simple as “sticking with the plan” or embracing an “eat less, move more” approach.

Celebrate Success

Make a concerted effort to celebrate accomplishments and successes, especially if they are not tied to a specific number on a scale.

Minds Must be Changed

Health and fitness professionals see it all the time: Dietary restrictions and exercise help clients melt away pounds fairly quickly, with peak results occurring about 6 months out. But without ongoing weight management, 50% of people regain their lost weight within 5 years, and many do it much sooner (Montesi et al. 2016).

We now know that willpower and compliance may not be enough to overcome the body’s natural tendency to revisit its set-point weight. Given these obstacles, fitness pros and clients might be better off focusing on lifestyle changes centering on achievable goals for nutrition and exercise.

Making that transition requires us to understand the interplay of diet, activity and metabolism. Furthermore, we have to translate the complexities of set-point weight into simple, direct language that clients can easily understand. And finally, we must agree that a healthy lifestyle does not require a low BMI or a picture-perfect body shape.

Most studies suggest that after weight loss of 10% or more of baseline body weight, metabolic adaptation kicks in and the body tries to return to its baseline weight (Muller, Endele & Bosy-Westphal 2016). Thus, people who lose substantial amounts of weight face a constant battle to counteract metabolic forces prodding them to eat more and exercise less.

People who have succeeded in this battle—losing more than 10% of body weight for more than 1 year—tend to share similar habits:

- Diet. Their daily lifestyle includes a portion-controlled, low-calorie, low-fat diet (including breakfast).

- Activity. They exercise for at least 1 hour per day, weigh themselves at least weekly and spend less than 10 hours per week watching televison.

Source: The National Weight Control Registry, nwcr.ws/research .

It’s only natural for fitness pros and clients to wonder if it’s possible to recalibrate set-point weight. Unfortunately, the evidence is not encouraging. Set-point weight is determined by genetics, environmental exposures and many other variables we don’t fully understand. It’s not easy to calculate set-point weight—studies have not established whether it’s determined in adolescence, pregnancy or middle age—or if it’s perhaps “programmed” even earlier in life (Schwartz et al. 2017).

All these unknowns make it unclear how we might alter set-point weight, though most studies suggest that changing it through dietary or behavioral interventions is difficult.

Interestingly, metabolic adaptation does not seem to occur after bariatric surgery (Schwartz et al. 2017), which could represent a permanent resetting of body weight. This is likely part of the reason why bariatric surgery has significantly better weight loss outcomes than those achieved through diet and exercise. While appropriate for some people with severe obesity, bariatric surgery is not a practical option for most people.

References

Astrup, A., et al. 1999. Meta-analysis of resting metabolic rate in formerly obese subjects. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 69 (6), 1117–22.

Fothergill, E., et al. 2016. Persistent metabolic adaptation 6 years after “The Biggest Loser” competition. Obesity, 24 (8), 1612-19.

Knowles, M.S., Holton, E.F., & Swanson, R.A. 2011. The Adult Learner: The Definitive Classic in Adult Education and Human Resource Development (7th ed.). New York: Taylor & Francis.

Montesi, L., et al. 2016. Long-term weight loss maintenance for obesity: A multidisciplinary approach. Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity: Targets and Therapy, 9, 37–46.

Muller, M.J., Enderle, J., & Bosy-Westphal, A. 2016. Changes in energy expenditure with weight gain and weight loss in humans. Current Obesity Reports, 5 (4), 413–23.

Schwartz, M.W., et al. 2017. Obesity pathogenesis: An Endocrine Society scientific statement. Endocrine Reviews, 38 (4), 267–96.

Sumithran, P., et al. 2011. Long-term persistence of hormonal adaptations to weight loss. New England Journal of Medicine, 365 (17), 1597–1604.

Natalie Digate Muth, MD, MPH, RD

"Natalie Digate Muth, MD, MPH, RDN, FAAP, is a board-certified pediatrician and obesity medicine physician, registered dietitian and health coach. She practices general pediatrics with a focus on healthy family routines, nutrition, physical activity and behavior change in North County, San Diego. She also serves as the senior advisor for healthcare solutions at the American Council on Exercise. Natalie is the author of five books and is committed to helping every child and family thrive. She is a strong advocate for systems and communities that support prevention and wellness across the lifespan, beginning at 9 months of age."