50 Ways to Cut Calories

Review research about why diets and dieters continue to fail, and learn how small changes can lead to big results.

For the first time ever, overeating is a larger problem than starvation among the world’s overall population (Buchanan & Sheffield 2017). Losing weight—and, perhaps more importantly, not regaining it—is a challenge facing millions of people worldwide. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), global obesity rates have nearly tripled since 1975. Further, 1.9 billion adults (18 years and older) were overweight in 2016. Of those people, more than 650 million were obese (WHO 2017). In 2013, the American Medical Association House of Delegates declared obesity a “disease” requiring treatment because of the multiple medical, functional and psychological complications associated with it.

There are numerous “remedies” for being overweight or obese. People buy the newest weight loss books, cut out sugar, eat low-fat and/or low-carb diets, and try the latest quick-fix weight loss products or programs. Yet none of these “solutions” has resolved the obesity epidemic.

This article presents an energy balance update and contemporary understandings of why diets don’t work and why people are missing the mark. Fitness professionals can use the 50 easy-to-implement calorie-cutting ideas presented, along with information about the evidence-based small-steps approach, to help clients start off the New Year with a personalized, realistic and long-lasting healthy eating plan.

Why Do Diets Fail?

Dieting can be defined as a deliberate attempt to restrict food consumption and achieve (or maintain) a desired body weight (Buchanan & Sheffield 2017). The inherent message in many diet plans is that certain foods or food groups are making us fat, and we must largely or completely avoid them. Although numerous plans claim to be medically sound, the associated long-term, health-related benefits are incomplete, and the restrictive nature of these plans makes them difficult to follow and maintain. However, the diet industry continues to be focused on which foods we should eat. While this appears to be a successful sales and marketing approach, it doesn’t educate people about the negative effects of consuming large quantities of foods (and sugary drinks), a primary factor in ongoing global weight gain. The fact is, “The development of obesity by necessity requires positive energy imbalance over and above that required for normal growth and development” (Hall et al. 2012). There’s no way of getting around it—a person who eats and drinks too much is going to gain weight, and a person who seeks to lose weight must limit calorie intake.

What Do We Know About Dieters?

After decades of research investigating “the battle of the diets,” a new line of study is examining the psychosocial factors linked to successful and unsuccessful dieters (Buchanan and Sheffield 2017). Recent findings submit that a key factor in dietary success is adherence to the diet. Successful dieters have resilient adherence; how or why they develop this commanding capacity is yet to be determined.

This pioneering research also indicates that people who fail at dieting often adopt an “all-or-nothing” approach, thinking in a dichotomous way (i.e., their thoughts go in two directions) (Buchanan & Sheffield 2017). By contrast, those who are successful tend to think about dieting as a process in a continuum of changes. Personal trainers who work with dichotomous-thinking clients should acknowledge small weight management victories and openly discuss lapses in an effort to teach clients that successful weight management includes ups and downs. The research by Buchanan and Sheffield offers other insightful findings that can be helpful in client interactions (see the sidebar “Research Findings on Why Dieters Fail”).

Revisiting the Three Components of Energy Balance

Consumption of fat, protein and carbohydrate not only provides energy for daily living but also determines a person’s weight. A lean adult stores about 130,000 kilocalories of fat and may have ~35 billion adipocytes (fat cells), while an extremely obese individual can store ~1 million kcal of fat and may have ~140 billion adipocytes (Hall et al. 2012). Fat is stored primarily in the form of triglycerides.

Carbohydrate is stored as glycogen, which is bound to water, in the liver and muscle. Changes in carbohydrate storage often result in sizable shifts in fluid storage. The more carbohydrates are eaten and stored, the more fluid the body retains. Fat, by contrast, does not need any water to bind with it for storage in the body, and protein needs very little water. Therefore, a person who eats a higher percentage of carbohydrate (not necessarily more calories) will retain more water, thus increasing total body weight.

As little as 2%–10% of total food intake becomes waste and is excreted. The rest is absorbed and oxidized for energy, including growth, physical activity, cell maintenance, pregnancy and lactation, and other biological life processes. These physiological processes are fueled by the energy harnessed from fat (9 kcal/gram), carbohydrate (4 kcal/g) and protein (4 kcal/g). Some foods, depending on the type of fiber content they have, are not digestible and are thus not absorbed and used by the body (Hall et al. 2012).

Hall et al. explain that common energy balance components of interest in weight management include resting energy expenditure (REE), thermic effect of food (TEF) and activity energy expenditure (AEE). REE is the energy needed throughout the day to stay alive and does not include energy used for exercise. It represents two-thirds of the body’s energy needs and can vary widely between people, primarily according to body size (the greater the body mass area, the greater the REE needed to stay alive) and body composition (muscle versus fat). Resistance training, when performed regularly, directly affects muscle mass and may influence (i.e., increase) a person’s REE. The heart, brain, liver and kidney, which weigh relatively minor amounts, demand substantial energy for life and contribute pointedly to the body’s total REE. Interestingly, scientists believe that approximately 250 kcal/day of REE are not fully accounted for by differences or variabilities between people.

TEF is linked to food processing and digestion. Owing to its dietary composition, protein elicits the highest TEF, followed by carbohydrate and then fat. TEF varies between individuals.

AEE is the fuel used by the body via structured exercise and nonexercise movement (such as moving, shopping and completing daily chores). This is the factor with the greatest observable range, as many people move a lot during their waking day and exercise regularly, while others don’t move much at all (Hall et al. 2012).

The Small-Changes Approach to Combating Obesity

The small-changes approach was originally designed to support small lifestyle changes and prevent gradual weight gain (Hill 2009). It has evolved to be a wide-ranging strategy that incorporates minor changes in diet and physical activity to combat overweight and obesity. The concept is that small changes, such as cutting calories or making food substitutions, are much easier to implement and maintain than many traditional dietary interventions.

Four Reasons Why the Small-Changes Strategy May Work

A 17-member task force from the American Society for Nutrition, the Institute of Food Technologists and the International Food Information Council evaluated the efficacy of the small-changes obesity intervention. According to Hill, there are four major reasons why this approach may succeed:

- Small changes are more realistic to achieve and maintain than large ones. From years of research and observation, the committee concurred that large behavioral and lifestyle changes are the most difficult to sustain. However, small changes—such as simple food substitutions (i.e., replacing a 12-ounce regular soda with a glass of water with lime)—are quite doable and maintainable.

- Even small changes influence body weight regulation. Hill contends that most people in the United States gradually gain weight over time. He explains that a slight increase in energy intake (diet) combined with a slight reduction in energy output (exercise and physical activity) can be enough to create an “energy gap” of 100 kcal/day, with a stored body fat efficiency of about 50 kcal/day. Thus, as a mean average, countless people are gaining about 2 pounds (or more) of fat per year (Hill 2009).

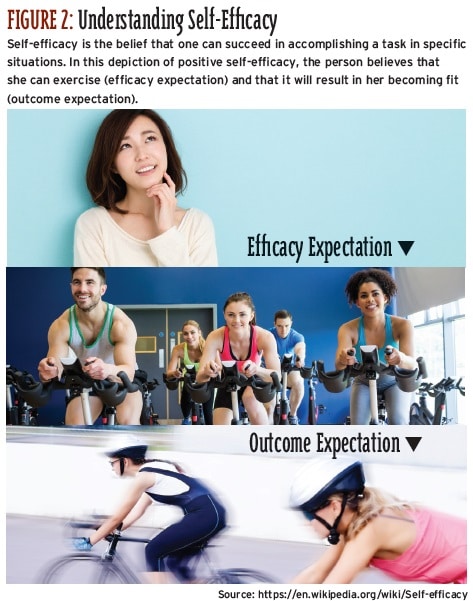

- Small, successful lifestyle changes improve self-efficacy. Self-efficacy is a person’s own sense of being capable of performing in a certain manner (in this case, making small lifestyle changes) to attain certain goals (in this case, losing weight and preventing weight regain) (see Figure 2). The task force suggests that positive changes in self-efficacy may motivate people to greater weight loss progress.

- The small-changes approach may be applied to environmental forces. Through triumphant marketing campaigns, business entities such as restaurants, food industries and fast-food establishments have created environmental cues that encourage excessive food intake. It is hoped that the small-changes approach can successfully restrain these environmental forces (see the sidebar “The Balance Calories Initiative” for one example).

The NEAT Approach: More Moving, Less Dieting

In 2005, James Levine and colleagues introduced the concept of nonexercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT), initiating a new line of research that has investigated the role of daily posture changes—standing, walking and moving—in combating weight gain and obesity. Levine and his team explained that NEAT comprises the energy expenditure of all nonplanned physical activities/exercises. They determined that in men and women who don’t exercise but who actively move during the day, NEAT contributes an additional 350 kcal of energy expenditure per day. Since the introduction of NEAT in 2005, scientists have sought to identify an optimal dose to recommend. (See “A Smart Way to Move” in the September 2017 issue of IDEA Fitness Journal to learn more about NEAT.)

Positive Lifestyle Changes

“Obesity is preventable” (WHO 2017). This is a crucial message for fitness professionals to convey to clients, along with the mindset that healthy eating is a habit, not a diet. With diligence and dedication, fitness professionals are leading the way to creating a healthier society. Encourage small changes to pave the way for big winning moments, one client at a time.

The following 50 tips to cut calories fall into eight categories:

Control Over Tempting Sensation Habits

1. Control triggers. For some people, certain foods trigger overeating. Be aware of these foods and find ways to avoid them by substituting satisfying, nontriggering foods.

2. Plan for parties. Before attending social events, dinner parties or catered occasions where there will be rich, high-calorie foods, eat a light protein-based snack (i.e., bean salad or yogurt).

3. Find a balance with favorite foods. It’s common to overindulge on favorite foods. Identify yours and commit to enjoying them, but don’t overindulge.

4. Be aware of breakfast starch overload. Many people treat themselves to a special bagel for breakfast, along with cream cheese, coffee and juice. Since a bagel today is equivalent to about five slices of bread, try a breakfast of egg whites, fruit and a quarter bagel instead.

5. Combat protein overload at dinner. Restaurants regularly entice customers with irresistible steak, seafood and chicken specials. Split a meal with a friend to cut the colossal protein calorie overload. Perhaps start the meal with a low-fat salad, and eat plenty of vegetables.

Simple Substitutions

6. Switch from a 3-ounce serving of meat to the equivalent of a meat alternative, such as lentils.

7. Switch from a serving of bread to a serving of rice cakes (about five rice cakes).

8. Switch from a 6-ounce glass of orange juice to a cup of cantaloupe.

9. Switch from a 1.5-ounce serving of cheese to an 8-ounce yogurt.

10. Switch from a half-cup of dried fruit to a cup of berries.

Wise Choices

11. Choose olive oil–based dressings instead of the creamy types.

12. Choose the grilled fish or chicken over fried options.

13. Choose whole-wheat or rye instead of white bread.

14. Order mixed berries for dessert rather than a slice of cheesecake, or ask for just a small serving.

15. Choose mustard over mayonnaise on sandwiches.

Surviving the All-You-Can-Eat Buffet

16. Choose only the foods you really enjoy.

17. Fill up on veggies, fruits and salads, and put the dressing on the side.

18. Skip foods with a lot of sauce.

19. Commit in advance to eating just one decent-sized plate, and avoid wearing loose-fitting clothes.

20. Eat slowly, savoring each bite as you (hopefully) engage in conversation with a friend or companion. Enjoy your meal with water rather than soda.

Clever Calorie-Cutting Ideas for Home Dining

21. When preparing and cooking multiple meals, freeze what you’re not immediately eating in single-serving containers. Bake casseroles in individual-size dishes.

22. To minimize overeating, serve the main dish on a salad or bread plate. Don’t leave food sitting on the counter.

23. Do not eat anything out of a bag or container. Place the food on a plate or in a bowl so you see precisely how much you’re eating.

24. Follow the “rule of one”: Have only one helping of each food group. The exception to this is vegetables.

25. Look out for added sugars (and their extra calories) in many packaged foods, including frozen dinners, salad dressings, breads and pasta sauce. Buy unsweetened oatmeal, cereal and yogurt, and sweeten them yourself with a tad of sugar or honey.

Smart Swaps

26. Make special requests when you go out to eat. For instance, swap out fries for vegetables or, when ordering a burrito, smart-swap cheese for extra tomato and lettuce.

27. Break the mayonnaise habit. Just one tablespoon of mayonnaise can have over 50 calories (depending on the brand).

28. Spice your tea or coffee with cinnamon, which helps stabilize blood sugar and is a good source of vitamin K and iron.

29. Choose the miniature versions of desserts.

30. Order appetizers as your meal.

31. Avoid the oversized food and drink portions that most restaurants serve; stick to regular-sized portions or try the kiddie size if there is one.

32. Smart-swap tomato-based sauces for creamy ones.

33. Choose thin pizza crust instead of deep-dish.

34. Avoid monster 18-ounce margaritas, which add more than 400 calories to a meal.

35. De-fat your caf├® latte. A medium 18-ounce latte made with whole milk has 265 calories. A small 12-ounce latte made with fat-free milk has 125 calories.

Guiltless Fast Food

36. Pay attention to your personal hunger meter. Stop eating when you feel comfortable, not full.

37. Order small sizes of all food options and enjoy the meal with a seltzer, sparkling water, iced green tea, or water with lemon. Sweet drinks—a go-to with fast-food meals—are a major source of added sugars. The verdict is still out on the health consequences of diet beverages. There is emerging evidence that some sugar substitutes may upset metabolic processes, possibly leading to weight gain.

38. Stay away from anything that says “double” or “triple.”

39. Steer clear of any meals that say “supersize,” “mega,” “biggie” or “jumbo.”

40. Be aware that some no-fat and low-fat meals have a fair number of calories.

Winning Ways to Live

41. Do not keep sugary drinks in the house.

42. Choose a low-calorie meal starter, such as salad or soup, to help prevent overeating later in the meal.

43. Order salad dressings on the side. Often even healthy, “low-calorie” salad dressings can be deceptively high in calories owing to the amount used.

44. Beware of the breadbasket. The bread-and-butter habit can add hundreds of calories to your meal. In fact, one slice of white bread with butter is 116 calories—and the bread may make you hungrier. The carbohydrate in it may trigger insulin production, which increases hunger. Send the breadbasket back, or ask your server not to bring bread to the table in the first place.

45. Be judicious with the chips and salsa when you go out for Mexican food. Practice moderation.

46. Prune your meal. Literally trim the meal you have chosen to eat. For example, if you’re eating a burger, take off the bun to save around 160 calories.

47. Be mindful of your alcohol consumption. There’s nothing wrong with appreciating a drink something but be aware of the calories you’re consuming.

48. Eat more whole fruits, which contain lots of fiber, vitamins, minerals and antioxidants.

49. Eat a little lean protein at most meals. This goes a long way toward making you feel satisfied.

50. Final reminder: If you truly want to lose weight and prevent weight regain, find sustainable ways to cut back on calories. In addition, keep progressing your cardiovascular and resistance training workouts.

In a research summary, Buchanan & Sheffield (2017) declare that their findings make it clear that professionals working with weight management clients need to design individual interventions that can be tailored to the changing needs of each client. Following are some additional take-home messages:

Media messages confuse dieters. Many dieters feel conflicted and torn between foods they are motivated to eat and foods they are told to restrict. Some consensus might alleviate their confusion. Reflect for a moment on this: For the past 10 years, there has been an ongoing vigorous debate about the efficacy of low-carbohydrate versus low-fat interventions for optimal weight loss. How bewildering this must be for a lot of people!

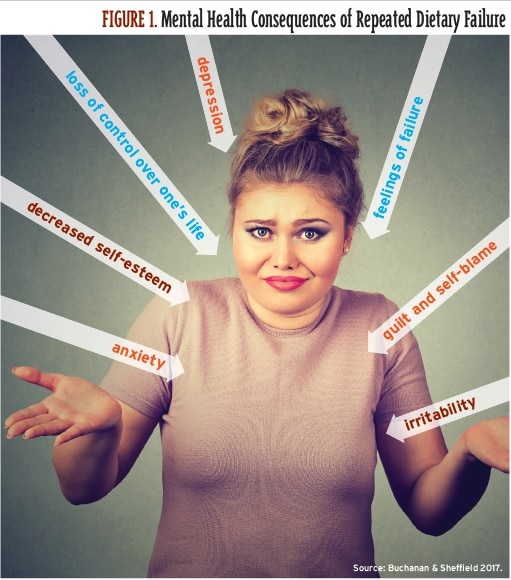

Many dieters experience high levels of body dissatisfaction and poor self-esteem. Repeated diet failure becomes a negative predictor for weight loss success. See Figure 1 for the mental health consequences of repeated diet failure.

The goal of health improvement does not motivate people to lose weight. Achieving changes in appearance is the principal motivation for many dieters.

Dieters tend to return to their previous eating habits. Regardless of whether a diet is successful or not, regression is common. This suggests that people see a diet as a phase, not a lifestyle change.

Many dieters grapple with food cravings. The restrictive nature of some diets leads many people to crave or intensely focus on certain “forbidden” foods. This can lead some dieters to periodically lose control and eat until full, a behavior called disinhibited eating.

Some dieters experience changes in self-perception. If these people deviate from their diets, they may describe themselves negatively (e.g., “I have no willpower; I’m weak”). They base their self-worth on their dietary success, which can contribute to feelings of low self-esteem.

Here’s an example of the small-changes approach in action. The Balance Calories Initiative is a landmark effort to decrease beverage calories in the American diet, and some major beverage companies have signed on (Alliance for a Healthier Generation 2016). These companies have committed to

- introducing no-, low- and mid-calorie beverages;

- reformulating full-calorie beverages to contain fewer calories per ounce; and

- engaging in marketing efforts to help retailers change shelf layouts so that consumers’ attention is drawn to reduced-calorie options and smaller package sizes.

The reported changes in beverage-drinking habits from the program’s launch in 2014 to 2015 were slight. However, officials remark that driving change of this magnitude takes time, and beverage companies are committed to providing consumers with smaller sizes and information about consuming less sugar. The small-changes approach shows that concerned public health organizations can successfully collaborate with private sectors to combat obesity.

References

Alliance for a Healthier Generation. 2016. Alliance for a healthier generation and American beverage association issue first progress report on reducing beverage calories. Accessed Oct. 2, 2017: healthiergeneration.org/news__events/2016/11/22/1646/alliance_for_a_healthier_generation_and_american_beverage_association_ issue_first_progress_report_on_reducing_beverage_calories.

American Medical Association House of Delegates. 2013. Recognition of obesity as a disease. Resolution 420 (A-13), 2013. Accessed Oct. 24, 2017: npr.org/documents/2013/jun/ama-resolution-obesity.pdf.

Buchanan, K., & Sheffield, J. 2017. Why do diets fail? An exploration of dieters’ experiences using thematic analysis. Journal of Health Psychology, 22 (7), 906-15.

Hall, K.D., et al. 2012. Energy balance and its components: Implications for body weight. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 95, 989–94.

Hill, J.O. 2009. Can a small-changes approach help address the obesity epidemic? A report of the Joint Task Force on the American Society for Nutrition, Institute of Food Technologists, and International Food Information Council. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 89, 477–84.

Levine, J.A., et al. 2005. Interindividual variation in posture allocation: Possible role in human obesity. Science, 307, 584–86.

WHO (World Health Organization). 2017. Obesity and overweight. Accessed Oct. 24, 2017. who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/.

Young, L R. 2005. The Portion Teller. New York: Morgan Road Books.

Len Kravitz, PhD

Len Kravitz, PhD is a professor and program coordinator of exercise science at the University of New Mexico where he recently received the Presidential Award of Distinction and the Outstanding Teacher of the Year award. In addition to being a 2016 inductee into the National Fitness Hall of Fame, Dr. Kravitz was awarded the Fitness Educator of the Year by the American Council on Exercise. Just recently, ACSM honored him with writing the 'Paper of the Year' for the ACSM Health and Fitness Journal.