Nutrition Adherence: Making Lifestyle Changes That Stick

These tips can help you motivate clients to stay on a healthy diet for the long haul.

Research has shown that the best weight loss plan is the one people can stick with for the long term (Johnston et al. 2014). For some, that may be a low-carbohydrate, high-protein diet. For others, it may be a high-carbohydrate plan that’s low in saturated fat. Yet another group may need a complete macronutrient balance.

The principle extends beyond dieters. How do some people, driven mostly by a desire for better health, follow eating plans like Paleo so religiously? What about the athlete training for an event who perfectly deploys sports nutrition principles? Or the person with gluten intolerance who successfully avoids even miniscule amounts of gluten?

On the other end of the spectrum, what makes some people unable to maintain even the smallest change? The science is far from complete, but a growing body of research offers clues we can piece together to help clients make nutritional behavior changes and keep to them.

The Psychology of Adherence: Age-Old Behavior Change Principles Still Apply

Many factors influence adherence, which the World Health Organization defines as “the extent to which a person’s behavior—taking medication, following a diet, and/or executing lifestyle changes—corresponds with agreed recommendations from a health care provider” (Sabaté et al. 2003). Although there’s no universal measure of nutrition adherence, we can assess it by tracking diet plan attrition rates and attendance in treatment sessions. Client self-monitoring can also be used to assess adherence (Leung et al. 2017).

Understanding what affects nutrition adherence can enable health and fitness professionals to do the most good when working with clients. It may also minimize feelings of frustration or even failure when clients do not change despite all efforts to convince them that it’s the best thing they can do for their health and well-being.

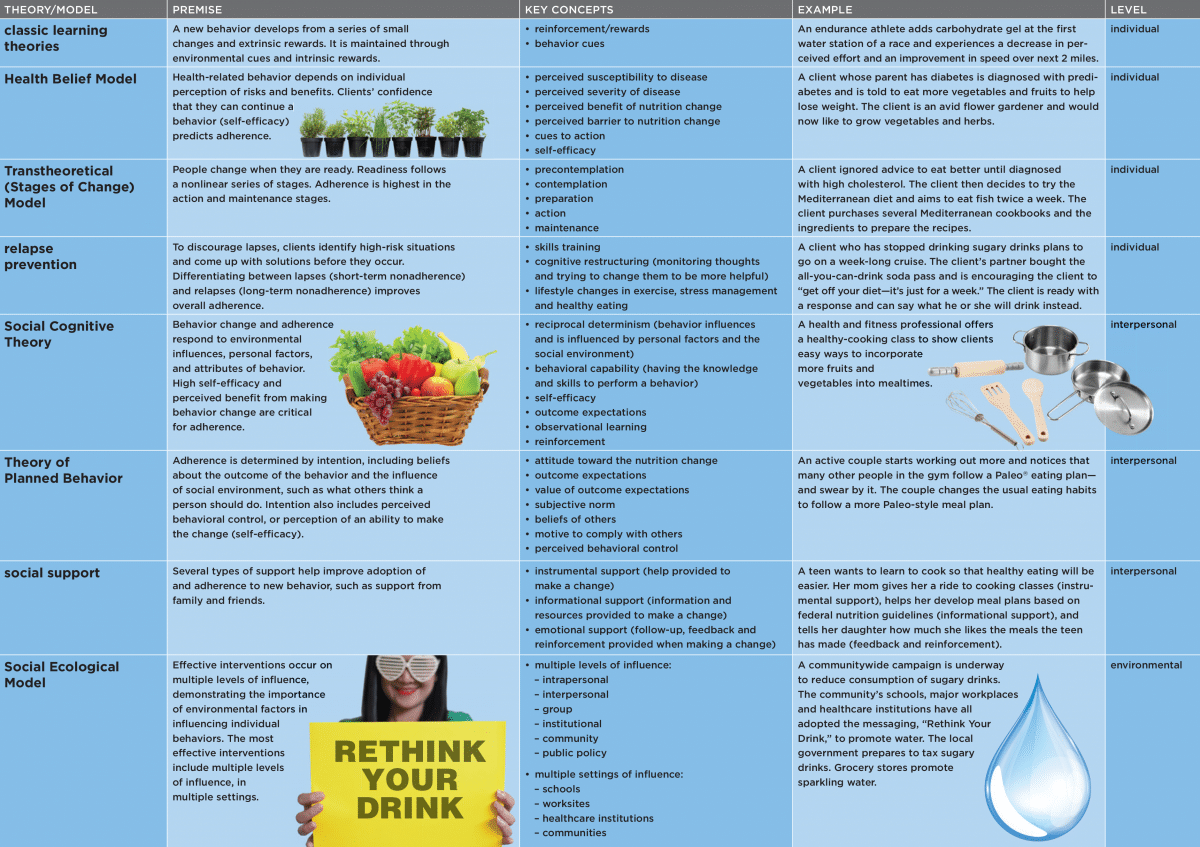

Adherence research is rooted in psychology and behavioral science. Behavioral theories aim to explain why and how people change and how well new behaviors “stick.” Fundamentally, these theories presume people can use cognitive processes such as planning and decision-making to pursue goals. Many different behavioral theories can inform a discussion of adherence to nutrition changes (see “Behavior Change Theories and Nutrition Adherence,” below.).

12 Ways to Boost Adherence to Diet Plans

Health and fitness professionals cannot influence all of the variables that affect people’s ability to change (see “5 Crucial Behavior Change Variables,” below). But there is plenty you can do to improve adherence to nutrition recommendations. Integrating these 12 strategies into your nutrition-related coaching sessions and programs will help build clients’ self-efficacy (i.e., confidence in their ability to sustain a dietary change).

1. Evaluate and customize. Start by assessing readiness to change. Using this assessment, you’ll then tailor your nutrition recommendations to a person’s stage of change. One study suggests that low adherence to a nutrition recommendation can result when a client is not motivated to change (the precontemplation stage), lacks family and social support, or has a negative view or understanding of the recommended nutrition changes (Estrela et al. 2017) (see the Transtheoretical Model in “Behavior Change Theories and Nutrition Adherence,” below).

On the other hand, people most likely to adhere to a nutrition change have already moved to the action or maintenance stages of change. They’re often older and more educated, with better baseline diets and exercise behaviors (Leung et al. 2017).

2. Educate with a three-step model. When sharing nutrition information with clients, consider using the “elicit-provide-elicit” model to encourage change (Miller & Rollnick 2012). “Elicit,” the first step, uses open-ended questions, in this case to identify the client’s baseline dietary knowledge. “Provide,” the second step, means delivering information with the client’s permission, which builds baseline knowledge. In the third step, “elicit” means you’re assessing the client’s understanding of the information provided.

A low level of nutrition knowledge is associated with poor adherence, while increased knowledge is a facilitating factor for adherence (Estrela et al. 2017). “Elicit-provide-elicit” lets you deliver information in a way that supports autonomy and strengthens your therapeutic alliance.

3. Stay flexible and keep it simple. Make sure the nutrition recommendations you provide are flexible enough to incorporate a client’s unique preferences. Include clear objectives, focusing on gradual changes and following up with a multiprofessional and interdisciplinary program (Estrela et al. 2017). The lower the complexity, the greater the therapeutic adherence.

Specifically, low adherence is associated with inflexible dietary plans that do not account for people’s preferences and whether they have negative views of restrictive eating plans. A more successful program takes into account a person’s beliefs, customs and concerns about treatment (Estrela et al. 2017; Van Horn et al. 2016).

4. Teach clients to self-monitor. Self-monitoring is a great way to promote longer-term adherence to nutrition recommendations (Van Horn et al. 2016). Help clients find a sustainable way to track and monitor nutrition intake—through a food log (written or video), for example. Apps such as MyFitnessPal and MealLogger can help, especially when clients are in a social setting.

5. Teach SMART goal-setting. Clients can learn to set specific, measurable, attainable, relevant and time-bound goals. Initially aim for small, easily achievable behavior-oriented goals that focus on adding a new desired behavior, rather than taking away an old behavior. This helps to create successful experiences early.

For example, a SMART goal might be to eat fruit and/or a vegetable at each meal for the next week. Achieving one SMART goal sets the stage for continued success.

6. List what works—and what doesn’t. Together with each client, create a list of factors that will make the nutrition changes easier and other factors that might make them more difficult. This helps to identify strong supports for making the nutrition change and overcoming barriers.

7. Teach relapse prevention and problem-solving. Lapses are a normal part of behavior change. Help your clients identify scenarios that might trigger a lapse, such as a vacation or certain foods in the home, and then problem-solve how to address potential hazards.

Incorporating relapse prevention and problem-solving skills training into nutrition coaching sessions can enable clients to address the barriers to adherence (Middleton, Anton & Perri 2013) by providing a structured way to troubleshoot challenges before they happen (see “A Step-Wise Approach to Problem-Solving Skills Training,” below).

8. Improve cooking skills. One study looking at adherence to the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (re: milk, whole grains, fruits, vegetables) in fifth-graders and nonrelated adult caregivers, for example, found that one of the biggest barriers for the adults was lack of skills in meal and recipe preparation (Nicklas et al. 2013). Incorporate cooking skills training into coaching sessions whenever possible or refer clients to other community resources that can help them build those skills.

9. Provide long-term follow-up. Adherence improves with programs that include follow-up once or twice a month in the year after an initial intervention (Middleton, Anton & Perri 2013). This follow-up need not be in person: Studies suggest phone and online counseling are nearly as effective and can reduce the cost of extended care.

In addition, programs that supervise and monitor attendance improve adherence by boosting accountability (Lemstra et al. 2016). Using multiple intervention methods (in person, virtual, group, individual) also has a positive effect on adherence (Desroches et al. 2016).

10. Build social support into every program. Social support is not only critical to overall health; it also plays an important role in sustaining behavior change (Lemstra et al. 2016). Start by teaching clients how to build support in their personal lives for a behavior change, then help them recruit friends or co-workers who will change with them.

Programs can include a group-based intervention or peer coaches, “buddy programs” or social-support contracts—all of which have been shown to increase adherence (Lemstra et al. 2016). Programs can also lead to new networks created with social tools via the web or a smartphone app.

11. Practice what you preach. A role model that already practices the desired nutrition behavior can increase a client’s motivation and self-efficacy, especially if the client considers the model trustworthy, admirable and respectable. One caveat: The client needs to believe the modeled behavior is something he or she can accomplish.

12. Help clients get what they need. Sharing credible nutrition information is a major job function of most health and fitness professionals. After all, dietary intake greatly affects health, fitness and weight—common reasons for a person to seek out the expertise of a health and fitness professional to begin with. But information alone is not enough to shift nutrition behaviors and lead people to adopt healthier eating patterns. Clients succeed when health and fitness professionals help them access the necessary tools, support and skills to translate nutrition information into new behaviors—and ultimately to sustain a lifestyle change.

Behavior change theories are used to explain what drives a person to make a change and keep at it. Five key variables—person, condition, treatment, relationship with the healthcare provider, and environment—seem to play the greatest roles in determining whether a person will follow through on a nutrition recommendation (Sirur et al. 2009; Desroches et al. 2016).

Let’s walk through each of these five variables:

1. Person. Characteristics may include a person’s beliefs about nutrition; expectations of the change’s outcome; or their home life, behavior patterns, nutrition knowledge and skill in translating knowledge into daily behaviors.

2. Condition. Characteristics include severity or chronicity of a disease being treated. This also applies to diseases/conditions people try to avoid through nutrition changes, as well as outcomes they pursue such as weight loss, improved sports performance or more muscular strength.

3. Treatment. The difficulty, complexity and extent of nutrition changes required to best prevent or treat a condition—or optimize performance—play a role in how well someone follows through with a nutrition recommendation. For example, physicians often encourage a DASH eating plan for patients with hypertension or a Mediterranean diet for those at risk of heart disease. Patients who think the eating plan is easy to understand and follow are more likely to make the recommended changes. On the other hand, if a patient thinks the diet is too complex and hard to follow, adherence is unlikely.

4. Relationship with the healthcare provider. Adherence also depends on how well the client connects with the health and fitness professional and (when applicable) the extended care team. People look for engagement, trust, respect and understanding. Using client-centered communication techniques such as motivational interviewing helps to strengthen the relationship between client and provider.

5. Environment. People belong to a greater community, which includes their home, school, work and favorite social settings. The beliefs and culture around food and eating in these settings play an important role in determining nutrition intake and adherence. Moreover, food factors such as media and marketing, pricing, access, and policies influence nutrition adherence. These environmental factors are best understood in the context of the social ecological model (see the“ Behavior Change Theories and Nutrition Adherence” chart, above).

1. Identify potential problems

- Help clients recognize that problems are “normal” and can be planned for and managed.

- Use open-ended questions and reflective listening when encouraging the client to explore potential obstacles to continuing a behavior change. For example, “What is the most difficult part about maintaining this nutrition change?”

- Encourage the client to elaborate.

- Help the client detail factors that contribute to the problem.

2. Explore possible solutions

- “Tell me about a time in the past when you had this problem and overcame it.”

- “What might make it easier to continue this nutrition change?”

- “How might you address this problem?”

- Brainstorm to create a list of potential solutions.

3. Make a plan

- Detail the potential positive and negative consequences of several possible solutions.

- Choose a potential solution to pursue.

- Help the client create a process-focused SMART goal strategy that includes a series of steps to take when a problem arises.

4. Implement the plan

- Help the client put the agreed-upon plan into action.

- When problems emerge, implement the plan’s processes and evaluate their effectiveness.

5. Evaluate the plan

- Assess how well the chosen solution helped to solve the problem.

- If your problem-solving skills fall short, start again at step 2, exploring other possible solutions.

Source: Middleton, Anton & Perri 2013.

References

Brehm, B. 2014. Psychology of Health and Fitness: Applications for Behavior Change. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis.

Desroches, S., et al. 2016. Interventions to enhance adherence to dietary advice for preventing and managing chronic diseases in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (2), CD008722.

Estrela, K.C.A., et al. 2017. Adherence to nutritional orientations: A literature review. Demetra, 12 (1), 249–74.

Johnston, B.C., et al. 2014. Comparison of weight loss among named diet programs in overweight and obese adults: A meta-analysis. JAMA, 312 (9), 923–33.

HHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). 1999. Physical Activity and Health: A Report of the Surgeon General, Chapter 6: Understanding and promoting physical activity. Accessed July 25, 2018: cdc.gov/nccdphp/sgr/pdf/chap6.pdf.

Lemstra, M., et al. 2016. Weight loss intervention adherence and factors promoting adherence: A meta-analysis. Patient Preference and Adherence, 10, 1547–59.

Leung, A.W.Y., et al. 2017. An overview of factors associated with adherence to lifestyle modification programs for weight management in adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14 (8), 922.

Middleton, K.R., Anton, S.D., & Perri, M.G. 2013. Long-term adherence to health behavior change. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 7 (6), 395–404.

Miller, W.R., & Rollnick, S. 2012. Motiv­ational Interviewing: Helping People Change (3rd edition). New York: Guilford Press.

Nicklas, T.A., et al. 2013. Barriers and facilitators for consumer adherence to the dietary guidelines for Americans: The HEALTH study. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 113 (10), 1317–31.

Sabat├®, E., et al. 2003. Adherence to Long-Term Therapies: Evidence for Action. Geneva: World Health Organization. Accessed July 25, 2018: who.int/chp/knowledge/publications/adherence_full_report.pdf.

Sirur, R., et al. 2009. The role of theory in increasing adherence to prescribed practice. Physiotherapy Canada, 61 (2), 68–77.

Van Horn, L., et al. 2016. Recommended dietary pattern to achieve adherence to the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology (AHA/ACC) guidelines. Circulation, 134 (22), e505–29.

Natalie Digate Muth, MD, MPH, RD

"Natalie Digate Muth, MD, MPH, RDN, FAAP, is a board-certified pediatrician and obesity medicine physician, registered dietitian and health coach. She practices general pediatrics with a focus on healthy family routines, nutrition, physical activity and behavior change in North County, San Diego. She also serves as the senior advisor for healthcare solutions at the American Council on Exercise. Natalie is the author of five books and is committed to helping every child and family thrive. She is a strong advocate for systems and communities that support prevention and wellness across the lifespan, beginning at 9 months of age."