Virtual Fitness Assessments: How to Streamline Your Baseline

Take the guesswork out of assessing clients remotely and learn best practices for helping them meet their goals from almost anywhere.

It’s one of the first things personal-trainers-to-be learn when they’re studying for a certification exam. It’s the foundation of all good fitness programming, and it informs trainers about clients’ starting points and abilities. It provides subjective and objective data, and it’s a key component of a responsible trainer-client relationship. Assessment is the starting gun for the “race” toward any health and wellness goal, and as we’ve all heard, what gets measured gets managed. Now, as the fitness industry leans digital, we’re seeing more virtual fitness assessments.

Exercise is essential, after all, for boosting mental and physical well-being, promoting healthy aging, reducing disease risk, and much more. Strength training helps preserve muscle mass (and metabolism), while regular cardiovascular activity confers benefits that outweigh its risks for almost everyone (Whitfield et al. 2017).

As such, until the spring of last year, most trainers felt their positions in fitness facilities were reasonably secure, even though taking time for the gym may have seemed like a luxury or an afterthought for many people. Maybe during cold and flu season you’d pick up a bug, but, for the most part, the gym was as much a safe part of life as restaurants and movie theaters. Then came March 2020. The novel virus SARS-CoV-2, aka COVID-19, took over the world.

The pandemic disrupted life in myriad ways. Even if gym closing wasn’t required, many participants felt safer staying away. Where did that leave personal trainers? The main option was to go online and continue doing what you could. It was a steep learning curve for some, a seamless transition for others. But the client-trainer interaction requires more than a standard Zoom call or Facetime session; it demands nuance and skill, especially for client assessments.

Now, as the world turns its face toward a new era, fitness professionals stand ready with a mirror to reflect health and wellness. People of all ages who were previously skittish about technology have learned how to use—and are reasonably comfortable with—videoconferencing tools. Virtual fitness assessments are emerging as an area of growth and exploration.

See also: Virtual Training Assessments

Virtual Fitness Assessment Review

Online and virtual training isn’t new, and it’s likely here to stay. Not only is it convenient, but it allows trainers to reach previously underserved audiences, such as those who are new to exercise or have disabilities or medical conditions (Halsall-De Wit 2021). But what makes good virtual fitness assessments, and why do trainers bother?

One of the most critical things trainers need to understand before working with a client is how well the person moves (Stull 2021). An assessment provides crucial information that informs all aspects of program design, and there are numerous protocols to choose from. Arguably, the most important thing about a virtual fitness assessment is simply doing one, whether you choose something advanced and high-tech or you employ traditional, tried-and-true methods. The point is to establish a baseline and then monitor progress. When you have a defined starting point, it’s much easier to quantify and agree on progression. For example, if advancement is slower than a client anticipated, a trainer can show that developing technique, which may have been lacking before, takes time and is necessary for future improvement.

The American College of Sports Medicine’s guidelines for physical fitness assessment includes five measurable components: cardiorespiratory fitness, body composition, muscular strength, muscular endurance and flexibility (ACSM 2014). Other certification and educational organizations may differ slightly in what they consider to be standard; however, this is a good working model with a lot of room for exploration.

Sherri McMillan, MS, owner of Northwest Personal Training in Vancouver, Washington, does her assessments in three parts: postural assessment, movement analysis and flexibility assessment. Within those areas, she looks for detailed information, such as proper muscle engagement, and “gross deviations” in the head, upper back, shoulders and pelvis (McMillan 2010).

Another approach includes six steps: client intake, static postural assessment, overhead squat assessment, single-leg or split-leg assessment (depending on ability), loaded assessment, and dynamic assessment (Stull 2021). Industry leaders have developed many excellent techniques, the majority of which are valid, useful and applicable to a wide range of abilities. The new frontier involves accurately transferring this knowledge to the computer, tablet or smartphone. Clients have to feel secure enough to do the requested movements without physical assistance, while trainers must be able to explain from afar what they want a client to do—and then be able to assess the resulting movement on a screen.

Lessons From the Clinical World

Some protocols adopted by the medical community could serve trainers well during assessments.

While many aspects of training remotely are appealing, it’s natural to wonder how one manages client safety from far away. For those steeped in risk stratification or working with high-risk clients, assessing a client remotely while unable to hear their breathing or observe their pallor may seem too great a risk. And it’s not hard to find experts who would caution against “impersonal” training for those and other reasons, including the tendency of some clients to downplay fatigue or deny distress. These experts reason that the risks exceed the benefits, or at least they have done in past years (Abbott 2016).

Prior to the pandemic, these concerns might well have given trainers pause. During lockdown, however, when pros had to weigh the risks of doing nothing versus developing or maintaining clients’ fitness, the calculation changed.

The same thing was happening in the medical field. Cardiac rehabilitation experts, while trying to protect patients from COVID-19 infection, were also concerned about the effects of inactivity on disease progression and clinical severity for those in various stages of recovery from heart attack, other forms of critical heart disease and valve replacement surgery.

Data in Italy from implantable cardioverter-defibrillators, pacemakers that can shock a heart back into sinus rhythm, showed a dramatic drop in patient physical activity after lockdowns went into effect. In this vulnerable population, even a 25% decrease in exercise for just 2 weeks could completely undo the cardiovascular, musculoskeletal and metabolic benefits these patients had accrued (Sassone et al. 2020).

Weighing the risk of infection in a highly vulnerable population against an acute need for effective therapy, experts at the Cleveland Clinic developed a pandemic protocol to safely deliver exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation (CR). In conjunction with hospital infectious disease specialists, the Clinic developed safety protocols for in-person sessions, while also expanding telehealth options using whatever technology patients were comfortable with. In these ways, the Clinic was able to develop an adaptable model for other care providers to implement (Van Iterson et al. 2021).

Prior to the pandemic, there were few standard-of-care models for telehealth in general or CR in particular. Medicare beneficiaries constitute a majority of those requiring CR, and the presence or absence of Medicare reimbursement often affects other insurers’ coverage decisions (Berry et al. 2020; Van Iterson et al. 2021). Medical or hospital-based programs like CR may also require that the video connection be HIPAA-compliant to protect patient privacy. This can be burdensome for those with a poor internet connection, low bandwidth or an older computer.

While most training sessions do not entail the same health risks as CR, some protocols adopted by the medical community could serve trainers well—for example, verifying a client’s exact location and address so you can direct emergency personnel there, should the need arise.

See also: 5 Lessons From Virtual Fitness Companies

Meet Clients Where They Are

As a certified trainer, you probably managed clients’ risks, health and safety in person—at the gym or maybe in their homes—before the pandemic. Perhaps you evaluated clients using the Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (PAR-Q), developed in the 1970s, or the American Heart Association/American College of Sports Medicine Preparticipation Questionnaire (AAPQ), first written in the 1980s. PAR-Q and the original AAPQ would have sent more than 90% of clients older than 40 for pre-exercise screening by a physician, which, given the 1% prevalence of heart disease in this cohort, could be viewed as excessive. In fact, there was little evidence that these screens enhanced anyone’s safety; they did, however, create a barrier to participation (Whitfield et al. 2014).

In response to concerns that screening was overly conservative, ACSM introduced an updated exercise preparticipation screening algorithm in 2016. This protocol considers a client’s current exercise participation; any signs, symptoms or known history of cardiovascular disease or kidney disease; and the client’s desired exercise intensity (Abbott 2016; Whitfield et al. 2017).

By considering the physical activity clients are already doing, trainers can meet them where they are and progress appropriately. A health evaluation of any kind likely reduces risk for both trainer and client, no matter what program is proposed, but requiring an overwhelming percentage of otherwise healthy individuals to seek medical advice before exercising was a barrier. What an evaluation entails will vary from trainer to trainer, depending on the fit pro’s comfort level and certification(s) and the insurance carrier’s requirements (see “What About Liability?,” below, for more).

Some trainers will never be comfortable doing virtual fitness assessments. They may feel that a client is more likely to give honest health information in person and may worry that going remote could greatly increase their legal liability. One suggestion for online/remote coaching is to use the more rigorous, pre-2016 screening (PAR-Q/AAPQ), along with explicit waivers and contracts (Abbott 2016). Other trainers have been offering remote sessions since the days of VHS tapes and plan to continue.

Virtual Fitness Assessments: Best Practices

Several elements are critical for virtual fitness assessments and workouts to succeed.

Virtual fitness assessments may work in theory, but what about the practical application? What are other personal trainers doing, and how are they refining techniques?

Sam Berry, MS, performance coach at the Boothbay Harbor Country Club in Boothbay, Maine, has been training clients online since about 2008. He says this practice developed organically, using Skype. Berry was conducting research studies on childhood obesity while also working as a personal trainer. He describes his transition to virtual training as more of a “soft landing” than a hard pivot. Training clients virtually allowed him to reach more customers each week in the same number of hours he had previously spent on in-person sessions.

To evaluate new clients, Berry, a Functional Movement Systems (FMS) level 2 coach, takes clients through seven specific movements. They allow him to see what deficits, impingements or balance issues a client may have and to develop a corrective program (see “5 Tips From the Field,” below). FMS has a proprietary evaluation app that allows the practitioner to review movement qualitatively and to derive a quantitative score for future comparisons. Berry describes this virtual fitness assessment as a “blood pressure screening of movement,” adding that “people have to move well before they move often.”

Not surprisingly, several elements are critical for virtual fitness assessments and workouts to succeed: good internet service; the most current operating systems; a space free of distractions from pets, people and excessive ambient noise; and enough room for movement. As for equipment, Berry likes to keep it simple for clients to buy or make—he uses dowels and exercise bands and is a fan of body-weight exercise. He also encourages clients to wear a heart rate monitor and any other wearables they have, to help with accountability.

Anthony Carey, MA, founder of Function First in San Diego and inventor of Core-Tex®, has been training remotely since 1989 (he’s a trainer who used to mail VHS tapes back and forth with clients!). He founded Function First in 1994, specializing in corrective movement for clients with chronic pain.

Technology has helped Carey upgrade his process for virtual fitness assessments. “Now, our follow-up assessments can involve sharing footage from past assessments and showing side-by-side comparisons,” he says. “We can do real-time screen grabs, mark them up quickly and share for immediate insight. Since we are not out on the facility floor, we can have digital resources ready to go and share with a click for educational purposes. For example, if I am working with a client with lower-back pain and I have their health history ahead of time, I can share some anatomy images or video in real time to help them better understand the relevance of our exercise objectives.”

For Carey’s specialized practice, remote training is ideal because it eliminates geographical proximity as a prerequisite. He sees clients at most once a week and assigns home programs between appointments. Prior to the pandemic, he did see some clients in person, but since last year he’s trained everyone remotely. Clients fill out an extensive health history plus a consent form that indicates they are under no obligation to perform the recommended exercises. People work at their own pace, and Carey incurs no extraordinary liability.

For new-client evaluations, he provides specific instructions on what movements to film and from which angles (he specifies several to get a full view of their movement patterns). He evaluates a prospective client’s posture while standing still and, for example, during squats and balance moves. The assessment is not quantitative, but it allows him to see how someone moves and what modifications will alleviate pain. Carey uses a biomechanical software app that allows him to provide audiovisual feedback to clients regarding their current movement patterns and desired modifications. He does not evaluate or focus on cardiovascular fitness.

As a long-time remote practitioner, Carey is an expert on cuing, a critical skill for trainers who don’t have the option of hands-on correction. He says many fitness pros need to develop better understanding and use of prompts that do not rely on anatomic descriptions or assume kinesthetic awareness. He gives this example: “If I wanted to see how someone’s hips move in the frontal plane while standing, facing the camera, depending on their age, I might say, ‘Do you remember the dance the bump’? Then I would ask them to pretend they were ‘bumping’ their partner to the left and then to the right. Or if they are familiar with hockey, I would use the cue of a hip check.”

Erin A. Mahoney, MA, founder of First31 and EMAC Certifications in Scottsdale, Arizona, shares more cuing expertise. She says technical trainers who use tactical cues in a traditional setting may struggle in the virtual world and recommends they work on developing verbal cues that produce optimal results. “Pay attention to which words get your clients into the right form,” she explains. “Don’t use words that only trainers know, such as, ‘Retract and depress your scapulae.’ Instead, opt for everyday language, such as, ‘Make your neck long and open your chest.’ Show clients what they’re doing versus what you want them to do.”

Jeff Payne, who co-owns Commence Fitness & Sorta Healthy in Southington, Connecticut, with his wife, Alexis, started doing virtual training when in-home training clients, a couple, moved away but wanted to continue. “This was my first foray into remote training,” he says. “When COVID-19 lockdowns started, we began offering virtual training to current clients we knew would be a good fit. We have a few clients who continue to see us virtually because they really enjoy it.”

Some of the challenges Payne encountered early on concerned communication and repetition. “In person, it’s easy to see their form, walk around them, ask lots of questions, hand them dumbbells, get weights set up, etc.,” he says. “When [clients are] on their own, and you’re just in front of a tiny screen, this becomes more difficult. It definitely involves a lot of ‘Can you turn your camera a bit for me?’ and questioning how things feel, ensuring that a client is comfortable moving the weights they are using and keeping the session flowing.”

Payne says it can be difficult to see all movement patterns, imbalances, etc., via webcam because “you can only see the person in the view they provide you.” His recommendation is to look at movement patterns “in a simplified way” and test the client “in a way that makes sense for being at home, in limited space, without a lot of equipment.” He summarizes it this way: “Essentially, how can you tell someone how to do something, have them execute it the way you want them to, but then also be able to see where they need work?”

Payne believes virtual fitness assessments are best suited to clients who either don’t have serious strength goals or don’t have many injuries or limitations. “If people are looking to lose weight or just get or stay fitter or healthier, then they would be the ideal virtual clients, because they can work with limited equipment and still reach their goals,” says Payne. “Generally speaking, most people have a couple of dumbbells, some resistance bands and maybe a stability ball, but they don’t have a ton of space. If someone is looking to lose weight, this works out just fine.”

Regarding the nuts and bolts involved in virtual fitness assessments, Payne recommends propping your computer or phone on a high table or tripod so that you have enough room to demonstrate moves and don’t have to play with positioning. Keep a variety of equipment on hand so you can quickly pull things out to show clients. “One of the most important aspects in virtual training is verbal feedback, so ask clients how things feel . . . and don’t be afraid to ask them to angle themselves or their phones/computers differently to see better.”

See also: Tips on Teaching Virtual Fitness Classes

A New Service to Master

Working remotely is a dream for some trainers and the least-bad option for others. By now, you likely know where you fall along that spectrum. Whether you want to increase your income stream or to dabble in remote training to see if it works for you, there are many resources to get you started. Make sure that your insurance coverage is in order and specific to what you’re doing; that you have the appropriate space, free of distractions such as noise, pets and family; and that you think ahead about what clients will have to do to be prepared. No one is going to appreciate losing session time to technology glitches or uncertainty about what to do or where to be, so create a checklist with pertinent details so that clients can be ready.

The COVID-19 pandemic forced pervasive changes in our lives, not all of them terrible. The convenience, broad reach and (now) well-understood nature of remote offerings opened up new possibilities for trainers interested in exploring them. Our main focus should remain the health, safety and well-being of our clients, whether we counsel them up close or from afar. Innovative ideas on assessing and training clients in the post-pandemic era will continue to emerge, even as we relish being able to meet in person once again.

From Shift to Gift

An August 2020 survey examined the pandemic’s effects on personal trainers’ earnings (Schuler n.d.). Results showed that 58% of personal trainers had lost some or all of their income, 23% were furloughed or laid off, and 6% had yet to find a new job at survey time. Then again, 21% of trainers surveyed were making more money, and about the same percent had retained their usual income.

Surprising no one, online trainers were making significantly more money in 2020 than in previous years (Schuler n.d.). The changes and shakeups in the fitness world may have felt game-changing and sudden to many, but according to trend-spotters, remote training and coaching have been on the horizon for years; the pandemic simply made the shift immediate and more visible (Kufahl 2021).

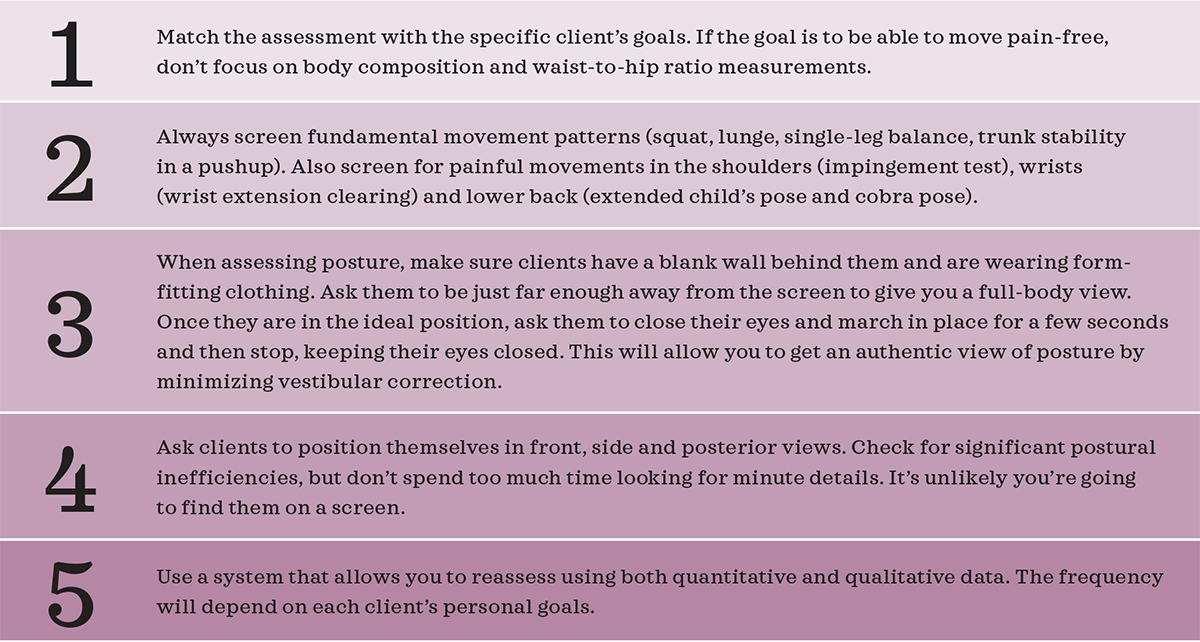

5 Tips From the Field

Sam Berry, MS, performance coach at the Boothbay Harbor Country Club in Boothbay, Maine, has been training remotely for more than a decade and shares the following tips on doing virtual assessments:

What About Liability?

Last year, as fitness professionals pivoted overnight to continue serving their clients, some pros switched to outdoor training, in parks or parking lots, while others offered classes using videoconferencing software (e.g., Zoom, Microsoft Teams, Google Hangouts). Many may have done so without pausing to update liability waivers or research software options. In the moment, these concerns would have felt less important than keeping clients active and income streams intact.

The National Strength and Conditioning Association and the American Council on Exercise have published advice to trainers on managing risk and liability, both remotely and in person. A key component is ensuring that liability coverage is tailored to what a trainer actually does; simply buying a generic policy is not the way to go. Other critical documents are an umbrella insurance policy (to protect other assets) and explicit, personalized waivers that require clients to attest that all information they have provided is accurate and honest to the best of their knowledge. These documents help to protect the trainer-client relationship if and when an injury or mishap occurs (ACE 2020; NSCA 2017).

Oliver Sowards, assistant vice president and program executive of Lockton Affinity LLC in Overland Park, Kansas, says IDEA members who sign up for insurance coverage through IDEA are covered “when livestreaming with a client or if the insured asks the client/visitor to their website to sign a waiver for accessing any videos that the insured makes available to view or download.” Sowards offers the following two examples:

When streaming, the insured can see the client, so if the client requires medical attention, the insured can notify the proper authorities.

Regarding video download, since the insured cannot see the client, the visitor/client must accept responsibility, stating that he or she is aware of the risks and will not hold the insured responsible should the visitor/client become injured as a result of the video download.

For more information about liability insurance, visit www.ideafit.com/professional-liability-insurance.

Translating Process: Real World to Virtual

The most important part of doing virtual assessments is realizing you have to find a way to adapt. Erin A. Mahoney, MA, founder of First31 and EMAC Certifications in Scottsdale, Arizona, is a virtual training expert and has insider tips that will help streamline the translation from in-person to remote.

“Fitness assessments are so important that you can’t ignore them completely,” says Mahoney. “Further, you can’t rely on the physical environment. You need to commit to making this work with the flexibility and understanding that it will just look a little different.” The following decision-making process may help:

Which assessments are critical to my online personal training business? You might have to scale back some of what you’re currently doing. Either way, think about the assessments you did in a traditional setting (if making the transition) and how you used them in your program design. For example, you probably did body composition assessments. Most clients are looking to lose body fat, and it’s how they determine success, so you really can’t overlook this type of assessment in most cases. On the other hand, you may have done one-repetition maximum tests to determine their starting strength level and how much weight clients could lift safely. If you performed the 1-RM but never factored it into your programming or gauged a client’s success from it, this test might not be necessary.

How can I make these assessments work virtually? Determine how you’ll conduct assessments. If you need to do a cardio assessment, something like the 3-minute step test may not work. Some clients may not have access to a step, and setting up a metronome could be too complicated. Instead, opt for something different, such as the 12-minute walk/run test. If you use body fat calipers, don’t send clients elsewhere to get this measurement. Instead, be willing to use a circumference measurement calculation to get an estimate.

How will I conduct these assessments? Will the clients record themselves, or will you watch in real time? The answer may depend on the assessment. While it might be better to do measurements live, a recording could be optimal for assessing movement. You can slow down a recording and pause it to confirm your findings.

How will I fully prepare the client and myself for the assessment? Provide all the supporting communication or instructions in advance. This will help you maintain consistency in your virtual assessment process and outcomes.

Companies That Specialize in Virtual Training

Virtual Personal Training

-

iFIT (Freemotion) https://www.ifit.com

-

Moxie.xyz https://moxie.xyz

-

BridgeAthletic http://bridgeathletic.co

Personal Trainer Business Management

-

My PT Hub http://mypthub.com

Club and Studio Management

-

GroupExPro https://groupexpro.com

-

ClubReady https://www.clubready.club

-

Paramount Acceptance http://paramountacceptance.com

Wearables, Trackers and Equipment

-

Blazepod https://www.blazepod.com

-

Jawku Speed https://jawku.com

-

Exer https://www.exer.ai/

-

MyZone https://www.myzone.org/

-

Reaxing https://www.reaxing.com/

-

Inside Tracker https://www.insidetracker.com/

All of the Above

-

Mindbody https://www.mindbodyonline.

com/ -

Wellnessliving https://www.wellnessliving.

com/ -

Trainerize http://trainerize.com/

-

Fitgrid http://fitgrid.com/

-

Sutra http://sutra.com

References

Abbott, A.A. 2016. Online impersonal training risk versus benefit. ACSM’s Health & Fitness Journal, 20 (1), 34–38.

ACSM (American College of Sports Medicine). 2014. ACSM’s Health-Related Physical Fitness Assessment Manual. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

ACE (American Council on Exercise). 2020. Legal considerations for virtual personal training. Accessed June 2, 2021: acefitness.org/education-and-resources/professional/expert-articles/7659/legal-considerations-for-virtual-personal-training/.

Berry, R., et al. 2020. Telemedicine home-based cardiac rehabilitation. Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation and Prevention, 40 (4), 245–48.

Halsall-De Wit, J., 2021. A European perspective on what’s coming in 2021 and where to focus your efforts. In P. Kufahl (Ed.), Fitness Industry Trends to Watch in 2021. Accessed June 2021: pages.questexnetwork.com/rs/294-MQF-056/images/ClubIndustry_ResourceBeat_Final.pdf.

Kufahl, P. (Ed.) 2021. Fitness Industry Trends to Watch in 2021. ClubIndustry.com Accessed June 2021: pages.questexnetwork.com/rs/294-MQF-056/images/ClubIndustry_ResourceBeat_Final.pdf.

McMillan, S. 2010. The components of a good fitness assessment. ClubIndustry.com. Accessed June 2021: clubindustry.com/step-by-step/components-a-good-fitness-assessment.

NSCA (National Strength & Conditioning Association). 2017. Understanding risk management as a fitness professional. Accessed May 27, 2021: nsca.com/education/articles/career-articles/understanding-risk-management-as-a-fitness-professional/.

Sassone, B., et al. 2020. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on physical activity in patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation and Prevention, 40 (5), 285–86.

Schuler, L. n.d. Personal Trainer Salary Survey (2020): COVID’s Impact on the Fitness Industry. Personal Trainer Development Center. Accessed June 2021: Theptdc.Com/Personal-Trainer-Salary-Survey.

Stull, K. 2021. A six-step guide to effective movement assessments. National Academy of Sports Medicine. Accessed June 2021: blog.nasm.org/a-guide-to-movement-assessments.

Van Iterson, E.H., et al. 2021. Cardiac rehabilitation is essential in the COVID-19 era. Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation and Prevention, 41 (2), 88–92.

Whitfield, G.P., et al. 2014. Application of the American Heart Association/American College of Sports Medicine adult preparticipation screening checklist to a nationally representative sample of US adults aged ≥40 years from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001 to 2004. Circulation, 129 (10), 1113–20.

Whitfield, G.P., et al. 2017. Applying the ACSM preparticipation screening algorithm to U.S. adults. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 49 (10), 2056–63.

Jennifer Klau, PhD

Jennifer Klau, PhD, has been a fitness professional since 1992. A former master instructor for the Spinning® program and an unapologetic science geek, she is known for her engaging presentations and her ability to make complex information accessible.