To Grow Healthier, Happier Adults, Raise Fit Kids

How fitness pros can encourage a new generation of healthy young people.

Today’s inactive kids are tomorrow’s unhealthy adults. Our society will pay the price for young people’s profound lack of exercise if we fail to turn this trend around. Few behaviors more significantly influence child health than physical activity. Yet children and adolescents are not moving enough, at the expense of their own health as well as that of their communities. More needs to be done to support families and society in raising fit kids.

Fortunately, health and fitness professionals have the knowledge and experience to teach everybody the benefits of physical activity—including our kids. Even if you have no children among your clientele, you can do a lot to encourage changes that will produce a generation of energetic young people who like to move.

Youth Exercise: How Much Is Enough?

The advantages of keeping kids active are well-known (see the sidebar “Benefits of a More Active Generation of Children and Adolescents”). But how much exercise do they need? Before you set out to support and inspire a generation of fit kids, you need to recognize the “ideal” goal posts. The 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee recommends that children aged 6–13 get the following:

- Cardiovascular exercise on most days—at least 60 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous activity, such as walking at a brisk pace, jogging, skipping rope, biking or playing ball sports.

- Muscle-strengthening exercise, such as resistance training and calisthenics, at least 3 days a week. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends targeting all major muscle groups. Start kids with no load and incrementally progress them after they’ve mastered technique. Program 2–3 sets of 8–15 repetitions for at least 8 weeks (AAP 2008).

- Bone-strengthening exercise, such as jumping rope and tumbling, at least 3 days a week (PAGAC 2018).

Don’t Forget Preschoolers

Studies have found strong evidence that physical activity among 3- to 5-year-olds can decrease the risk of excessive weight gain and improve bone health (PAGAC 2018). Research suggests adults should ensure that, each day, children aged 1–4 get at least 180 minutes of structured and unstructured exercise (free play) in a variety of activities and environments to help them develop movement skills (Lipnowski et al. 2012). Even infants need to be physically active several times daily, mostly through interactive, floor-based play. All activities must be varied, enjoyable and age-appropriate.

10 Ways To Close The Youth Activity Gap

There’s a vast gulf between young people’s current activity levels and the recommendations summarized above. But there are many things you can do to narrow this gap. Consider these 10 actions:

1. Model An Active Lifestyle

As a fitness professional, you’re a positive role model for physical activity. Use this to empower other activity models in a child’s life—not only parents but also grandparents and other loved ones. Start with small steps, such as going for walks in the community, taking the stairs instead of an elevator or escalator, encouraging walking meetings and active outings, and walking or biking to work, if possible.

Next, move on to bigger steps, like leading a walking school bus or a free walk in the park. Consider partnering with initiatives such as Walk with a Doc, where physicians and other health professionals lead free community walks. Also make a point of telling adult clients how their actions can inspire their kids and grandkids to make physical activity a priority.

2. Tailor Activities To Age, Stage And Ability

Pediatric specialists often repeat this mantra: Children are not just “little adults”—and no two of them are alike. An important option when developing or promoting physical activity programs for children and adolescents is to break things down by age and stage of development. Activities can provide a wide degree of engagement and results based on a child’s age and ability (see Table 1).

3. Target Their Interests (And Make It Fun!)

The best physical activities for kids are interesting and enjoyable. Unlike adults, children have a hard time slogging through workouts in the hope of achieving a health goal. Every child prefers something different, and you have to find activities a kid would do regardless of the health benefits.

Research indicates that children who participate in sports, have more outdoor time, and walk or ride their bike to school are most likely to meet physical activity guidelines (Wilkie et al. 2018). Encourage your adult clients to identify physical activities that the whole family can enjoy together. Some families might even be interested in testing out and developing a new skill together.

4. Track Their Movements

A good way to know whether a child meets exercise guidelines is to track baseline activity. This is more difficult to do with children than with adults, but a few tools can help.

For example, pedometers or activity trackers can estimate steps taken in a day. If procuring objective measures isn’t feasible, parents can get a baseline marker by noting their child’s activities in a typical day and approximating how close they come to meeting exercise recommendations. For example, a child who walks to school (20 minutes), jumps rope and does gymnastics in physical education class (20 minutes), plays on the monkey bars at recess (10 minutes), and plays soccer with his siblings at home after school (20 minutes) meets the physical activity guidelines for cardiovascular fitness (jumping rope, walking, soccer), as well as for muscle strengthening (gymnastics, monkey bars) and bone strengthening (jumping rope, gymnastics).

Some school districts implement fitness testing. For instance, the FitnessGram®, developed by The Cooper Institute in 1982, is used in thousands of schools across the United States. An assessment of this type shows parents their child’s fitness level based on standardized measures of cardiovascular fitness, muscular strength and endurance, flexibility, and body mass index.

5. Question The Status Quo

The key to helping kids meet exercise guidelines is to provide support that builds physical activity into the day. Indeed, this is why school is an ideal place for kids to get their 60 minutes of exercise. Encourage families to question preschools and daycare providers about their priorities on physical activity and motor skill development.

Health and fitness professionals should urge schools to add more physical activity. If changing the school day is out of reach, however, you are not out of luck. Persuade parents to ask schools how their children can be active:

- Can parents encourage their kids to walk or bike to school, if it’s feasible?

- Are there before-school options for physical activity, such as a running club or playground free play?

- How often do children have PE class? How long do classes last, and how much moderate-to-vigorous activity happens?

- How many recess periods are there in a day? How long are they? What do children typically do during recess?

- What after-school exercise opportunities are available?

- For children who like sports, what does the school offer beyond what parents can provide?

Gym or health club members can also ask about activities for children while their parents work out. Better yet, they can ask what opportunities there are for kids and parents to be active together. Maybe a local facility offers family weight training or strengthening programs.

6. Encourage A Healthier Approach To Diet

Kids should eat healthful, balanced diets that fuel physical activity. Nutrition guidelines for adults also apply to children: Eat a primarily plant-based diet rich in fruits, vegetables, legumes, whole grains, nuts and seeds. Minimize intake of added sugars and of processed and refined grains.

Physical activity should not be used to rationalize or “make up for” a lousy diet. Sports drinks are overconsumed and rarely needed to fuel physical activity in kids.

7. Control Screen Time

Screen time interferes with physical activity and disturbs sleep, reducing its quality and duration (Hale & Guan 2015). A great way to manage screen time comes from the “Family Media Plan” developed by the American Academy of Pediatrics (healthychildren.org/English/media/). Key recommendations include avoiding or restricting screen time during meals and within 1 hour of bedtime. Both parents and children should heed this advice.

Yes, these changes can be difficult because screens are so addictive (Lissak 2018). However, modeling a healthy approach to screen time is just as important as modeling healthy eating and physical activity.

8. Focus On Sleep Quality

One of the many benefits of physical activity is better sleep. The 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee found strong evidence that exercise improves sleep measures in adults, including total sleep time, sleep efficiency, time it takes to fall asleep, sleep quality and rapid-eye-movement (REM) sleep (PAGAC 2018).

There wasn’t enough evidence to draw conclusions for children and adolescents—most likely because of a lack of research rather than a lack of benefit. Parents will surely embrace any exercise program that is likely to improve a child’s sleep, since the benefits of well-rested children extend to the whole family.

9. Troubleshoot Barriers

Any behavior change can be difficult to integrate into a daily routine and maintain for the long term. Health and fitness professionals, especially those with skill in behavior change principles, can be especially effective at helping families troubleshoot difficulties in starting or maintaining a fitness program. Here are some common challenges:

-

- Socioeconomics. Many youth activity programs require a financial investment that low-income parents cannot afford.

- Safety. Many children lack access to safe play areas, especially in urban neighborhoods.

Time. Working families often cannot transport children to sports or other recreational activities. Many after-school and daycare programs do not help children get enough exercise.

- Physical health concerns. For children with obesity and other healthcare needs, exercise presents physical challenges. These youngsters may feel self-conscious or embarrassed when participating in activities with their peers.

- Competing priorities and interests. If physical activity is not a priority for families and communities, it may not be a priority for children, either. Even if kids start out active, physical activity often plunges as they get older. This is likely because specialization increases for “elite” young athletes, while sports participation drops off for most other kids. Adolescents are less likely to have PE classes or other opportunities to be active as part of their everyday routines. Placing a special focus on providing fun, engaging options for teens is especially valuable.Families may experience these or different barriers to beginning an activity program. It is important to assess a family’s strengths and opportunities for increasing a child’s activity levels while also evaluating and troubleshooting the potential barriers.

10. Make It Stick For The Long Haul

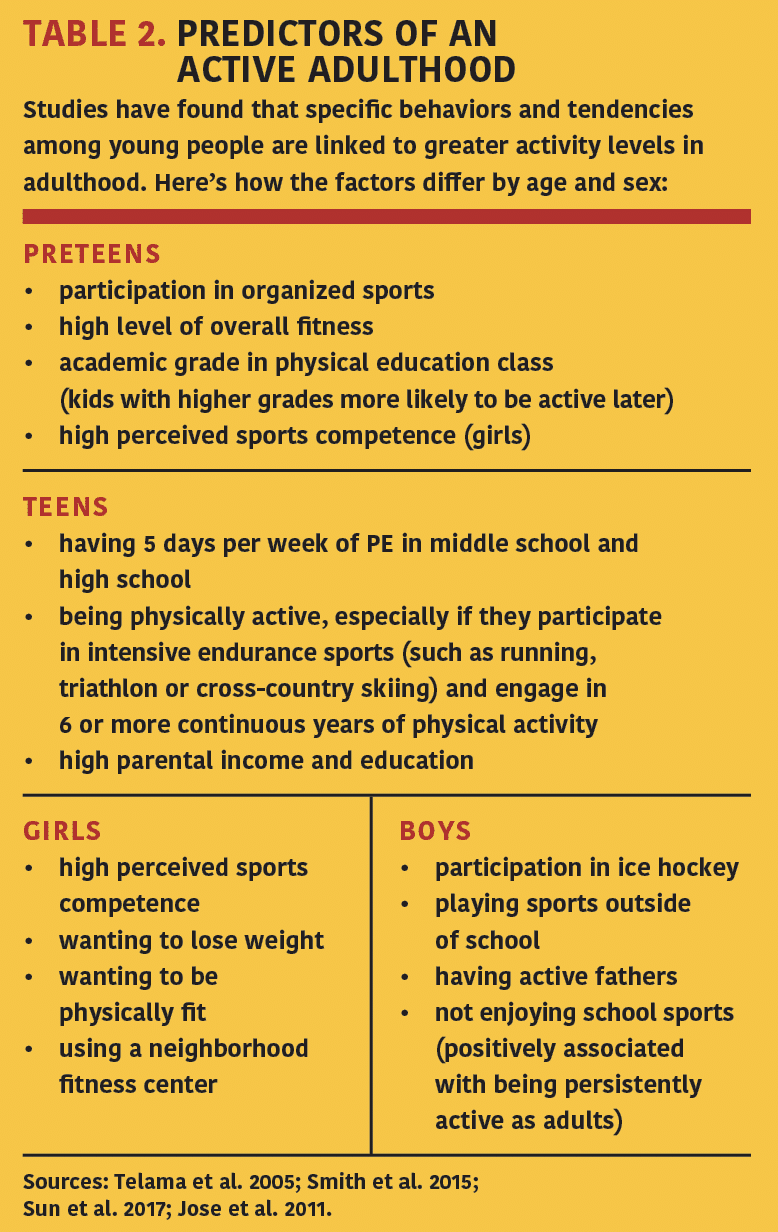

The first 6 months of a behavior change are the most tenuous, but if the change continues for that long, it is more likely to stick for the long term. This is equally true for kids and adults. Those who are active in childhood—and especially adolescence—are more likely to be active as adults, although, sadly, the percentage of physically active youth who become active adults remains quite low (Telama et al. 2005).

Table 2 highlights the factors in childhood and adolescence that predict adult physical activity levels. Focusing on these variables may help more children experience the powerful, immediate benefits of physical activity and the longer-term advantages of becoming an active adult.

Why Not Start Today?

It’s never too late to begin a physical activity program. If we as a society and as a profession do more to raise fit kids, we will go a long way toward growing happier, healthier adults.

Physical activity improves heart health, muscular fitness and bone health. It also reduces the risk of weight gain and increased adiposity (PAGAC 2018). One modeling study showed that if just half of kids met the physical activity guidelines, the number of children with overweight and obesity would decrease by 4%, saving $8.1 billion in medical costs and $13.8 billion in lost productivity (Lee et al. 2017). For kids with obesity, physical activity improves inflammatory markers, which may reduce cardiovascular and metabolic diseases in adulthood, although more research is needed (Sirico et al. 2018).

Regular physical activity also improves other key factors:

- It boosts academic performance. Studies find that acute bouts of physical activity and regular moderate-to-vigorous exercise improve cognition, including memory, processing speed, attention and academic performance in children aged 5–13 (IOM 2013).

- It improves behavior and sleep. These two areas are tightly tied to quality of life for kids and their families. With the stresses of daily life and an increasingly connected world, mental health is critical in children. Physical activity helps by reducing anxiety and depression. Lower levels of sedentary time are associated with higher perceived quality of life overall (PAGAC 2018).

Of course, health and fitness professionals already recognize the benefits of physical activity. The greater challenge lies in translating recommendations into action. Kids spend most of their day at school, yet only Oregon and Washington, D.C., meet the national recommendations for weekly physical education for elementary- and middle-school students. There is no federal law requiring minimum standards for PE, and while most states have some rules in place, fewer than half require a specific number of minutes per week. Even among the states that do, monitoring and enforcement often fall short.

Moreover, many physical activity mandates are unfunded, leaving school districts to rely on fundraising to hire PE instructors or find other ways to meet requirements (SHAPE 2016). In reality, kids get little physical activity during the school day, despite a recommendation from the Institute of Medicine (now known as the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine) to accumulate 60 minutes of exercise every day through activities before, during and after school (IOM 2013).

Away from school, many kids spend their extra time in front of screens. Kids 8 years old and younger average 2 hours 19 minutes of screen time per day (CSM 2017). Teens rack up an average of 9 hours of media (television, social media, internet, texting, etc.) per day, not including school or homework (CSM 2015). Teens who spend more time in front of screens and less time on nonscreen activities (such as physical activity) have lower psychological well-being (self-esteem, life satisfaction and happiness) than their less screen-addicted, more active peers (Twenge, Martin & Campbell 2018).

The young people most at risk for inactivity include adolescents—especially girls, minority children, and youth with special healthcare needs. The 2015 Youth Risk Behavior Survey found that just over 1 in 4 adolescents reported activity levels consistent with current guidelines, while 14.3% of students reported not being physically active for at least 1 hour on a single day in the prior week (Kann et al. 2016).

Objective measurement of activity by accelerometer showed that under 50% of children and fewer than 1 in 10 adolescents met the guideline of 60 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity daily (Li et al. 2016). Youth physical activity levels have decreased over time, except for the bright spot of increased sports participation among high-school girls (Bassett et al. 2015).

Infants. Before they learn to walk, babies need floor-based play and “tummy time” to develop basic skills like sitting up, rolling, crawling and pulling to stand.

Toddlers and preschoolers. Once they’re walking, youngsters should be getting 180-plus minutes of activity per day on the playground and in outdoor free play. Toddlers need to develop gross motor skills like walking, running, jumping, throwing and kicking. Preschoolers should build on gross motor skills while developing fundamental movement skills like swimming, tumbling, throwing and catching.

TABLE 2. PREDICTORS OF AN ACTIVE ADULTHOOD

References

AAP (American Academy of Pediatrics). 2008. Council on Sports Medicine and Fitness. Strength training by children and adolescents. Pediatrics, 121 (4), 835–40.

Bassett, D.R., et al. 2015. Trends in physical activity and sedentary behaviors of United States youth. Journal of Physical Activity & Health, 12 (8), 1102–11.

CSM (Common Sense Media). 2015. The Common Sense Census: Media Use by Tweens and Teens. Accessed June 18, 2018: commonsensemedia.org/sites/default/files/uploads/research/census_executivesummary.pdf.

CSM. 2017. The Common Sense Census: Media Use by Kids Age Zero to Eight. Accessed June 18, 2018: commonsensemedia.org/sites/default/files/uploads/research/0–8_executivesummary_release_final_1.pdf.

Hale, L., & Guan, S. 2015. Screen time and sleep among school-aged children and adolescents: A systematic literature review. Sleep Medicine Review, 21, 50–58.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2013. Educating the Student Body: Taking Physical Activity and Physical Education to School. Accessed June 18, 2018: nationalacademies.org/hmd/Reports/2013/Educating-the-Student-Body-Taking-Physical-Activity-and-Physical-Education-to-School.aspx.

Jose, K.A., et al. 2011. Childhood and adolescent predictors of leisure time physical activity during the transition from adolescence to adulthood: A population-based cohort study. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 15 (1), 53.

Kann, L., et al. 2016. Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2015. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Surveillance Summaries, 65 (6), 1–174.

Lee, B.Y., et al. 2017. Modeling the economic and health impact of increasing children’s physical activity in the United States. Health Affairs, 36 (5), 902–8.

Li, K., et al. 2016. Changes in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity among older adolescents. Pediatrics, 138 (4).

Lipnowski, S., et al. 2012. Healthy active living: Physical activity guidelines for children and adolescents. Paediatrics & Child Health, 17 (4), 209–12.

Lissak, G. 2018. Adverse physiological and psychological effects of screen time on children and adolescents: Literature review and case study. Environmental Research, 164, 149–57.

PAGAC (Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee). 2018. 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Scientific Report. Washington, D.C.: US Department of Health and Human Services.

SHAPE (Society of Health and Physical Educators). 2016. 2016 Shape of the Nation. Accessed June 18, 2018: shapeamerica.org/uploads/pdfs/son/Shape-of-the-Nation-2016_web.pdf.

Sirico, F., et al. 2018. Effects of physical exercise on adiponectin, leptin, and inflammatory markers in childhood obesity: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Childhood Obesity, 14 (4), 207–17.

Smith, L., et al. 2015. Association between participation in outdoor play and sport at 10 years old with physical activity in adulthood. Preventive Medicine, 74, 31–35.

Sun, H., et al. 2017. Correlates of long-term physical activity adherence in women. Journal of Sport and Health Science, 6 (4), 434–42.

Telama, R., et al. 2005. Physical activity in childhood to adulthood: A 21-year tracking study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 28 (3), 267–63.

Twenge, J.M., Martin, G.N., & Campbell, W.K. 2018. Decreases in psychological well-being among American adolescents after 2012 and links to screen time during the rise of smartphone technology. Accessed June 18, 2018: psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Femo0000403.

Wilkie, H.J., et al. 2018. Correlates of intensity-specific physical activity in children aged 9–11 years: A multilevel analysis of UK data from the International Study of Childhood Obesity, Lifestyle and the Environment. BMJ Open, 8 (2).

Natalie Digate Muth, MD, MPH, RD

"Natalie Digate Muth, MD, MPH, RDN, FAAP, is a board-certified pediatrician and obesity medicine physician, registered dietitian and health coach. She practices general pediatrics with a focus on healthy family routines, nutrition, physical activity and behavior change in North County, San Diego. She also serves as the senior advisor for healthcare solutions at the American Council on Exercise. Natalie is the author of five books and is committed to helping every child and family thrive. She is a strong advocate for systems and communities that support prevention and wellness across the lifespan, beginning at 9 months of age."