The Power of Exercise for the Autism Community

Discover how to adapt your best practices to help this underserved population find success.

Between the pandemic and the smart home gym revolution, personal trainers have seen many of their clients “virtually” disappear. While the market for personal training has clearly shrunk, there is a community that was never considered part of the market in the first place: those with autism.

Autism spectrum disorder is the fastest-growing developmental disability in the world, with recent data reporting one in 44 children diagnosed in the United States (CDC 2022; Christensen et al. 2016; Elsabbagh et al. 2012). To successfully exercise, people on the spectrum benefit from one-to-one instruction, motivation and a customized exercise routine. Personal training is a perfect fit for the way this community learns.

Research shows that for the autism community, exercise goes beyond the health-related benefits and can improve focus, on-task behavior and language development, as well as reduce maladaptive or stereotypical behaviors (Allison, Basile & MacDonald 1991; Elliott et al. 1994; Lang et al. 2010; Nicholson et al. 2010; O’Connor & French 2000; Ruggeri et al. 2020; Schmitz Olin et al. 2017; Tse, Liu & Lee 2021).

Fitness professionals have an opportunity to rise to the occasion and use their passion of teaching exercise to make a life-changing difference for those with autism.

Unique Characteristics of These Clients

There are three factors that make training a person with autism different than training neurotypical clients: 1) parents are typically involved, even with some adolescents and adults; 2) this community learns differently; and 3) many have been turned off from exercise or haven’t done it at all. It is critical to be educated and equipped when working with those with autism. Developing an exercise plan for an autistic individual that is 90% correct will most likely result in 100% failure.

There are proven tools and protocols that have built success in the classroom for those with autism, but these strategies rarely make it to the gym. To obtain success in exercise program design, fitness professionals must understand autism, educate themselves on using evidence-based practices for training this population, and create realistic goals for their new clients (Wong et al. 2015). When done properly, a foundation will be built, and quite possibly the person will become a client for life.

See also: Exercise and the Autism Population

Positive Impacts of Exercise on the Autism Community

Exercise interventions have shown to lead to a 37% improvement in symptoms of autism, specifically behavioral and academic improvement.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a developmental disability that can cause significant social, communication and behavioral challenges (CDC 2022). What many people do not know is that exercise is one of 27 evidence-based practices (EBPs) that can help achieve learning or developmental skills and goals for those with ASD. “Exercise is a strategy that involves an increase in physical exertion as a means of reducing problem behaviors or increasing appropriate behavior while increasing physical fitness and motor skills” (Wong et al. 2015).

A meta-analysis of 16 studies suggested that, on average, exercise interventions led to a 37% improvement in symptoms of autism, specifically behavioral and academic improvement (Sowa & Meulenbroek 2012). However, you cannot just put a person on the spectrum into an exercise session and expect those results. Exercise is often used in conjunction with other EBPs, such as verbal prompting and reinforcement and visual supports. Unfortunately, rather than receiving specialized exercise instruction in the schools, this population tends to be underserved.

Why Kids With Autism Need Our Help

Due to exercise’s impact on academics, many would assume that children are receiving exercise through physical education, but this isn’t always the case. Even though the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) and Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) support participation in school-based PE, many students with autism do not receive appropriate PE services nor access the full benefits from PE (IDEA 2019; ED 2015).

A population-based study indicates that U.S. adolescents with learning and behavioral developmental disabilities are 60% more likely to become obese. Although the study did not address PE’s role in obesity, the U.S. Government Accountability Office identified key PE challenges for students with disabilities, which include a lack of clarity regarding schools’ responsibility in PE, limited teacher preparation and budget constraints (GAO 2010). These key challenges could be contributing factors to the likelihood of those with disabilities becoming obese.

Evidence-Based Practices for Teaching

Autism is a spectrum disorder, meaning the characteristics of ASD, along with levels of support required, will vary from client to client (APA 2013). Successfully engaging a person with autism into any new activity—especially exercise—will take patience, flexibility and the use of evidence-based teaching practices. By nature, personal training already involves many of these best practices.

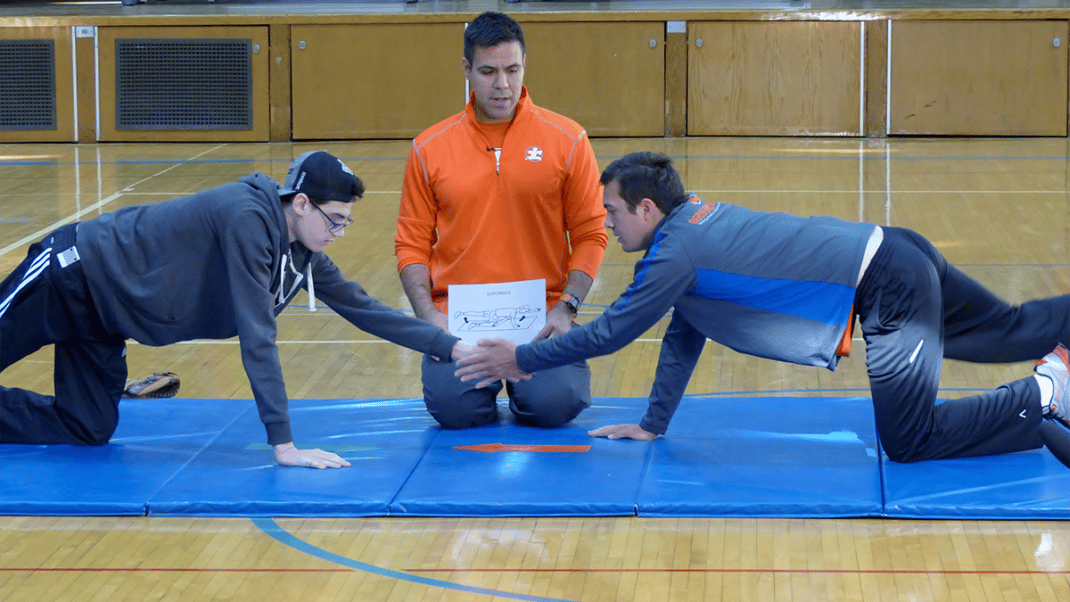

For example, when training a neurotypical client to do a bench press, in addition to verbally explaining it, you likely demonstrate how the exercise is correctly performed. If this is your approach, that demonstration is actually an evidence-based practice known as modeling. The research shows that modeling is often combined with other evidence-based strategies (Wong et al. 2015).

A proven practice used to teach those with autism are visual supports (e.g., photos or illustrations). Visual supports help bring structure, routine and sequence that many children with autism require to carry out their daily activities (Rao & Gagie 2006). Visual supports, when implemented correctly, allow students with autism the freedom to engage in life, regardless of impairment (Hodgdon 2007).

Visual supports and many other evidence-based practices are successfully used in special education classrooms to teach reading, writing and life skills. Using these same strategies to teach exercise will be familiar and effective for this population. See “Sample Session: 10 Minutes to Exercise Success,” right, for ideas on using visual support cards, motivational cuing, modeling and other EBPs to the greatest advantage.

See also: Training People With Disabilities

Inspiring (All) the World to Fitness

Parents of children with autism are looking for opportunities that will enhance their child’s quality of life and, at the same time, their interaction with others in the community. Personal trainers can open the door to inclusion and help those with autism reach their full potential.

Becoming an Autism Ready® Exercise Professional

Many people with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), if not most, benefit from visual supports. They can be especially helpful in a crowded or distracting gym. The pictures teach and show what is expected. As the saying goes, “A picture is worth a thousand words.” When working with those with autism, it really is!

Create Structure

Establishing structure and routine can be a powerful reinforcement for autistic individuals. Develop structure by staying consistent with exercises, scheduling and timing. Visual supports also help to establish structure.

Get Certified

The American College of Sports Medicine partnered with autism fitness industry expert Exercise Connection to create the Autism Exercise Specialist Certificate®. Supported by research, this was ACSM’s #1 Specialty CEC Course in 2021. Learn more on the Exercise Connection website at exerciseconnection.com/autism-exercise-specialist-certificate/.

Download the App

Embedded with six evidence-based teaching practices and supported in seven research studies, an app called Exercise Buddy leverages technology to empower those with autism to exercise in the gym, at community fitness centers and at home. It can be used by fitness professionals to create custom workouts and assess performance. Find it on the App Store or Google Play.

Sample Session: 10 Minutes to Exercise Success

When you embark on this mission, your goal is to get your new autistic clients through the first session in an enjoyable way. If you get them through the first session and wanting to come back, you’ve won!

When starting, you need to be like the tortoise, not the hare. A 2017 research study concluded that 10 minutes of low- to moderate-intensity exercise produces significant reductions in stereotypical behavior in those with ASD for the 60 minutes that follow the workout (Schmitz Olin et al. 2017). Ten minutes is an achievable starting goal for both you and your new client. Yes, they may physically be with you for a 45- or 60-minute session, but there is transition time between exercises or sets. And just like you spend time building the relationship with your neurotypical clients, you must do the same here.

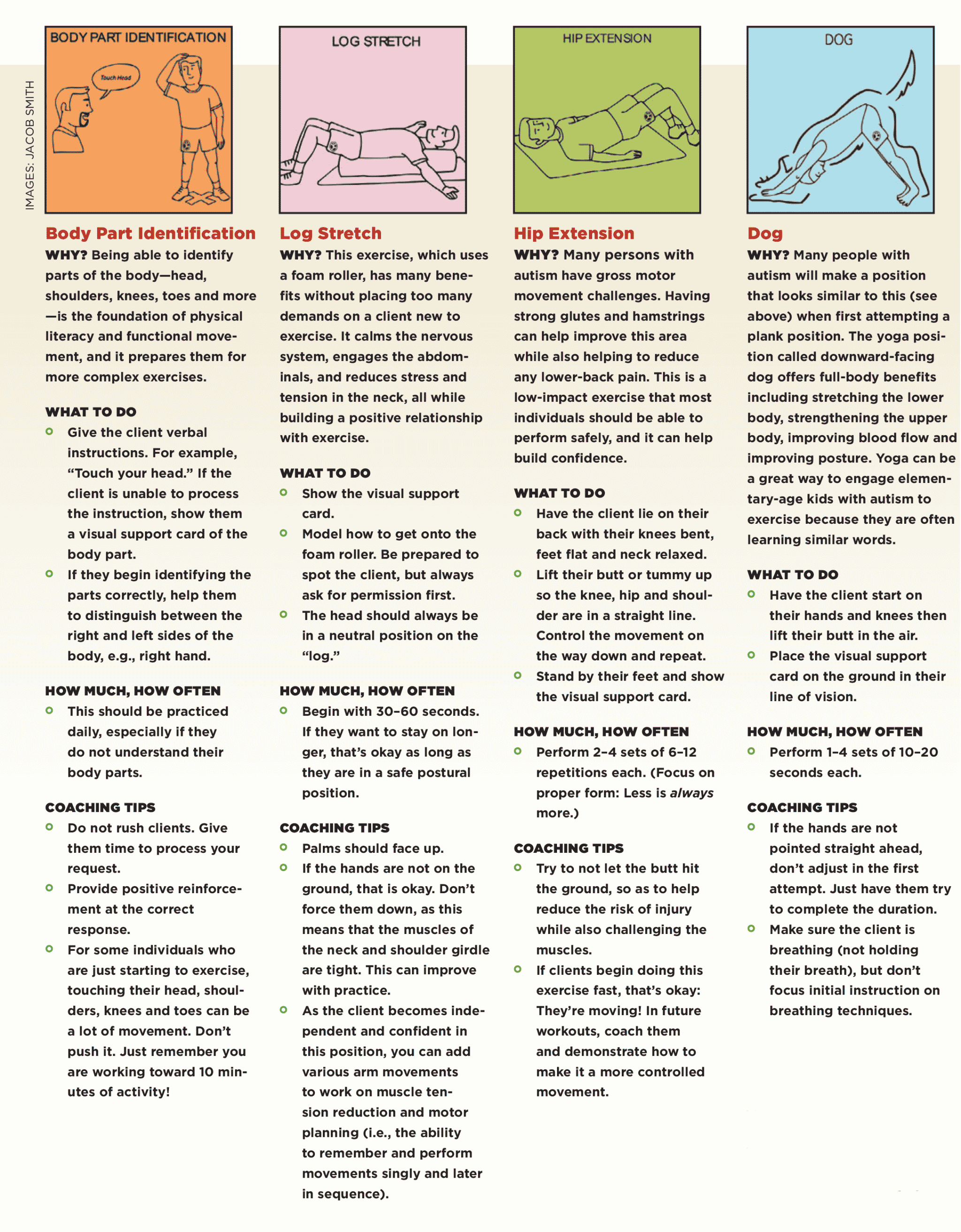

To get started, here are four exercises that those with ASD of diverse age groups, needs and abilities have used to make the exercise connection, along with examples of visual card supports and cues that involve modeling, motivation and other evidence-based practices shown to work well with this population.

References

Allison, D.B., Basile, V.C., & MacDonald, R.B. 1991. Brief report: Comparative effects of antecedent exercise and lorazepam on the aggressive behavior of an autistic man. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 21 (1), 89–94.

APA (American Psychiatric Association). 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2022. Autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Accessed May 7, 2022: cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/index.html.

Christensen, D.L., et al. 2016. Prevalence and characteristics of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 sites, United States, 2012. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report: Surveillance Summaries, 65 (3), 1–23.

ED (U.S. Department of Education). 2015. Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA). Accessed May 7, 2022: ed.gov/essa?src=rn.

Elliott, R.O., et al. 1994. Vigorous, aerobic exercise versus general motor training activities: Effects on maladaptive and stereotypic behaviors of adults with both autism and mental retardation. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 24 (5), 565–76.

Elsabbagh, M., et al. 2012. Global prevalence of autism and other pervasive developmental disorders. Autism Research, 5 (3), 160–79.

GAO. 2010. Students with disabilities: More information and guidance could improve opportunities in physical education and athletics. Accessed May 7, 2022: gao.gov/products/gao-10-519.

Hodgdon, L.A. 2007. Visual Strategies for Improving Communication: Practical Supports for School and Home, (1st ed.). Ventura, CA: Academic Internet Publishers.

IDEA (Individuals with Disabilities Education Act). 2019. Section 1400. Accessed June 8, 2022: sites.ed.gov/idea/statute-chapter-33/subchapter-i/1400.

Lang, R., et al. 2010. Physical exercise and individuals with autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 4 (4), 565–76.

Nicholson, H., et al. 2010. The effects of antecedent physical activity on the academic engagement of children with autism spectrum disorder. Psychology in the Schools, 48 (2), 198–213.

O’Connor, J., & French, R. 2000. Use of physical activity to improve behavior of children with autism: Two for one benefits. Palaestra, 22–27.

Rao, S.M., & Gagie, B. 2006. Learning through seeing and doing: Visual supports for children with autism. TEACHING Exceptional Children, 38 (6), 26–33.

Ruggeri, A., et al. 2020. The effect of motor and physical activity intervention on motor outcomes of children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Autism, 24 (3), 544–68.

Schmitz Olin, S., et al. 2017. The effects of exercise dose on stereotypical behavior in children with autism. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 49 (5), 983–90.

Sowa, M., & Meulenbroek, R. 2012. Effects of physical exercise on autism spectrum disorders: A meta-analysis. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6 (1), 46–57.

Tse, A.C.Y., Liu, V.H.L., & Lee, P.H. 2021. Investigating the matching relationship between physical exercise. and stereotypic behavior in children with autism. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 53 (4), 770–75.

Wong, C., et al. 2015. Evidence-based practices for children, youth, and young adults with autism spectrum disorder: A comprehensive review. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45 (7), 1951–66.

David Geslak

David Geslak is a published author, writes autism and exercise research articles, and has a TV show, “Coach Dave,” on the Autism Channel. In collaboration with the National Center on Health, Physical Activity and Disability (NCHPAD), he created an autism exercise video series that now has more than 500,000 views. He graduated from the University of Iowa with a degree in health promotion and is a certified exercise physiologist from the American College of Sports Medicine and a Certified Strength and Conditioning Specialist from the National Strength and Conditioning Association.