The Ultimate Guide to Resistance Training Techniques

10 advanced resistance training techniques that deliver results!

| Earn 1 CEC - Take Quiz

Resistance training (RT) and resistance training techniques are associated with a myriad of sports, physical, psychological and overall health benefits. Wackerhage et al. (2019) highlight that regular performance of RT improves muscle mass, strength and function and can have direct effects on the primary prevention of a number of chronic diseases.

Despite these impressive benefits, the evidence indicates that, from 2011 to 2017, between 69.7% and 70.9% of adults in the U.S. did not meet the muscle strengthening guidelines from the World Health Organization’s 2010 Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health. WHO recommends involving major muscle groups in muscle-strengthening activities on 2 or more days a week (Bennie et al. 2020).

Accordingly, there is a pressing need for new and innovative resistance training techniques that deliver effective results from programs. This article will highlight 10 advanced resistance training techniques that improve muscular fitness, strength and mass—and hopefully re-engage new and veteran clients!

1. Longer Eccentric Contractions

What Is It?

For any given exercise, repetitions are often described in three separate phases: eccentric, concentric and isometric contractions. The eccentric phase (muscle lengthening under load) receives a significant amount of attention in the literature because these contractions are associated with exercise-induced muscle damage, mechanical tension and metabolic stress, all of which have been associated with a hypertrophic adaptation (Krzysztofik et al. 2019; Kojic et al. 2021).

Thus, to provide a novel stimulus for clients, fitness pros can readily prolong the eccentric phase of each repetition by instructing the lifter to lower the weight slowly (e.g., 4 seconds instead of 1).

The Science

To assess the effect of eccentric duration, Kojic et al. assigned 20 untrained RT volunteers (9 female, 11 male, average age 24) to one of two groups: fast-eccentric (1 second) or slow-eccentric (4 seconds) contractions. Both groups performed an elbow flexion exercise (EZBar preacher curl) 2 days per week for 7 weeks. Volume (3–4 sets), load (60%–70% of 1-RM), effort (momentary muscle failure), and concentric-contraction duration (1 second) were matched.

Results indicated that both groups significantly increased their biceps brachii muscle thickness with no differences between groups. Both groups increased their 1-RM maximal strength from their baseline value, but data revealed that the slow-eccentric group had a larger average increase (+6 kilograms) than the fast-eccentric group (+3.3 kg).

Sample Programming

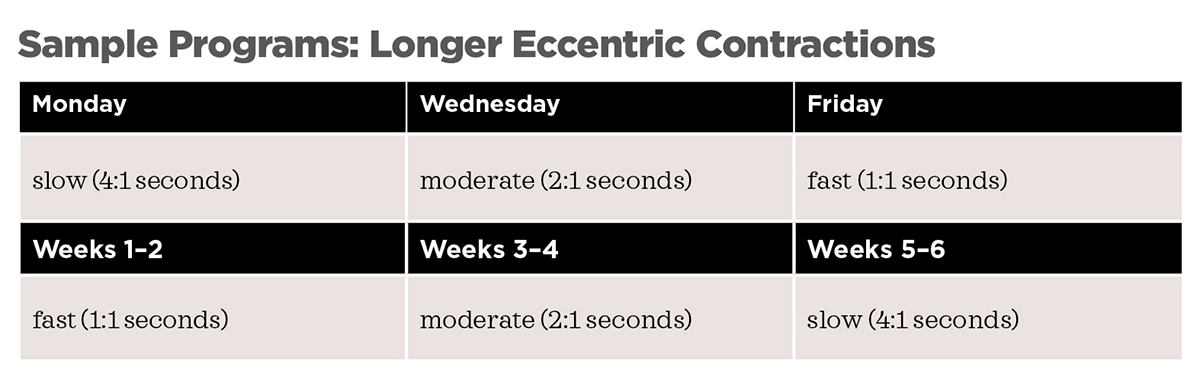

The study by Kojic and colleagues demonstrated that 1:1 (1-second eccentric contraction time: 1-second concentric contraction time) and 4:1 (4-second eccentric contraction time: 1-second concentric contraction time) tempos are both effective for hypertrophy and strength. We recommend fitness pros use both training styles. A well-rounded program may include an intermediate repetition tempo such as 2:1 (2-second eccentric time; 1-second concentric contraction time).

See the sample programs, below, for two examples you can use for any exercise in which eccentric contractions are varied daily or weekly.

2. Slow/Tonic Contractions

What Is It?

Slow/tonic contractions are a unique application of slower-repetition tempos that require a muscle to be under constant tension during a set. To perform slow/tonic contractions, lower the weight for 3 seconds and then raise the weight for 3 seconds, repeating all repetitions in this manner continuously during a set.

The Science

To assess the effect of slow/tonic contractions, Tanimoto et al. (2008) randomly assigned 36 non-RT men (average age 19) to one of three conditions: slow/tonic (3:3 seconds [3-second eccentric contraction; 3-second concentric contraction, repeat]); normal (1:1:1 seconds [1-second eccentric contraction: 1-second concentric contraction; 1-second rest, repeat]); or a nontraining control group.

Participants in the slow/tonic group trained with 55%–60% of 1-RM; volunteers in the normal group trained with 80%–90% of 1-RM. Exercise intensities on the slow/tonic and normal training groups were adjusted to an 8-RM intensity. Consequently, the slow/tonic training group developed a similar intensity to the normal speed group at an adjusted lower intensity, due to the slow movement tempo.

Both groups performed total-body lifting 2 days per week for 13 weeks and performed three sets of eight repetitions for every exercise (squat, chest press, latissimus dorsi pulldown, abdominal curl and back extension). Data revealed that both groups significantly and similarly increased their muscle thickness, total-body lean mass and total-body muscular strength.

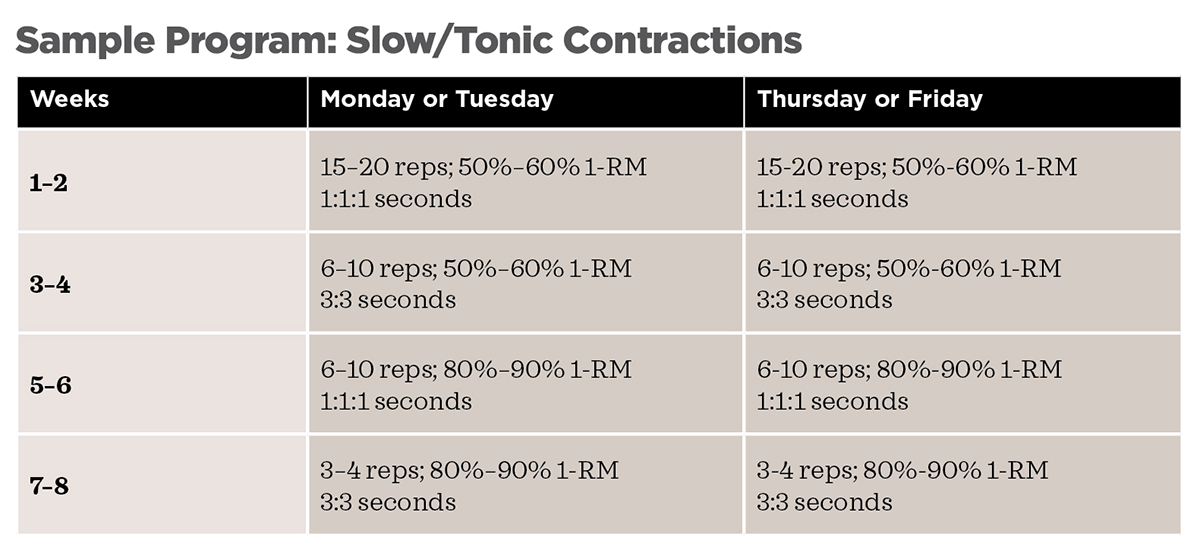

Sample Programming

The Tanimoto et al. study suggests that slow/tonic and normal tempo training are equally effective for hypertrophy and strength. For practical application, we recommend that fitness pros use a variety of intensities and repetition tempos that include hybrids of the programs used in this research. For effective programming, have clients perform total-body lifting 2 days per week and select individualized exercises for each client (see the sample program, below).

See also: 5 Resistance Training Workouts That Improve VO2max

3. Partial Range-of-Motion Training

Individuals may be limited in their ability to lift a given weight through the full ROM due to a sticking point, and partials may enable them to overcome this limitation.

What Is It?

Partial range-of-motion training, also known as “partials” by exercise enthusiasts, focuses on training the middle range of motion (ROM) of an exercise. It’s thought to elicit significant muscular tension by allowing a lifter to perform RT at a higher load compared to lifting with the full ROM (Schoenfeld & Grgic 2020).

Partial ROM training contributes to intramuscular mechanical compression, increased time under tension, enhanced glycolytic energy system involvement and the production of lactate, all of which may lead to increases in muscular strength and hypertrophy (Goto et al. 2019).

The Science

In a recent study, Goto and colleagues assigned 44 resistance-trained men to perform three sets of lying elbow extensions with either full or partial elbow joint range of motion at their 8-RM for 3 days a week for 8 weeks. The partial range-of-motion group performed elbow range of motion from 45 to 90 degrees, and the full range-of-motion group performed elbow range of motion from 0 to 120 degrees.

Study results showed that both groups significantly improved in the cross-sectional area of the triceps brachii and isometric strength of the elbow extensors. Interestingly, the cross-sectional area of the triceps muscle was increased significantly more after the partial range-of-motion training-—up 48.7% (114.5%), as compared with the full range-of-motion training-—up 28.2% (110.9%). These findings suggest that partials may positively aid in developing muscular hypertrophy.

Sample Programming

Partials and full ROM training do not need to be mutually exclusive. Individuals may be limited in their ability to lift a given weight through the full ROM due to a sticking point, and partials may enable them to overcome this limitation. Some researchers have suggested it is conceivable that combining partials with full ROM exercises may promote synergistic effects on muscle growth (Schoenfeld & Grgic 2020). Fitness pros are encouraged to incorporate partials into a client’s regular full ROM training.

Four examples of using partial ROM training during a set of body weight split squats:

- The client descends into full depth and performs half-repetitions to failure from full depth to half depth.

- From the starting position, the client performs half-reps to failure by only descending to half depth for each repetition.

- Have client perform full + half reps, where each full-depth split squat is followed by a half-depth split squat until fatigue occurs.

- Perform a sequence of partial reps at different depths by descending to ¼, ½, ¾ and full depth until fatigue occurs.

Applying partial ROM training to four consecutive sets of pushups:

- Perform pushups by de-scending to ¼, ½, ¾ and full depth until fatigue occurs.

- Repetitions to failure at the bottom-half ROM.

- Reps to failure at the top-half ROM.

- Starting from the bottom of the pushup, perform a bottom-half ROM rep followed by a full-ROM rep until failure is achieved.

4. Reverse Pyramid & 5. Linear Pyramid Training

What Is It?

Linear and reverse pyramid training are unique resistance training techniques that allow lifters to accrue high training volume while using a variety of intensities within the same session. Linear pyramid training involves increasing intensities as sets progress (light to heavy), while sets are performed in the opposite manner (heavy to light) during reverse pyramid training.

The Science

To compare the effect of pyramid training, Razmjou et al. (2010) recruited 34 untrained female participants (average age 18) and randomly assigned them to 6 weeks of linear or reverse pyramid training. Total-body lifting took place 3 days per week, and both groups performed the same six exercises: latissimus dorsi pulldown, knee extension, knee flexion, leg press, triceps extension and biceps curl.

For each exercise, both groups performed three sets of 10 repetitions at the following intensities: 50% of 10-RM, 75% of 10-RM and 100% of 10-RM (which was the only set performed to failure). The only difference between groups was the order in which sets were done, as the linear pyramid group went in the order of 50%-75%-100% of 10-RM and the reverse pyramid group went 100%-75%-50% of 10-RM, for each exercise.

Results indicated that both groups significantly increased their muscular strength for all six exercises, and the only difference between groups was detected for the biceps curl, for which the reverse pyramid group had a larger increase (+13 kilograms versus +10 kg).

Sample Programming

The study by Razmjou and colleagues demonstrates that both pyramid resistance training techniques are effective for increasing strength, and fitness pros are encouraged to use both when designing their RT programs for clients. For instance, clients may prefer linear pyramid training because the early sets serve as an extended warmup before attempting sets with heavier loads. Other clients may prefer reverse pyramid training because they would like to perform their heaviest set first and are lifting with lighter loads as the session progresses and fatigue accrues. We recommend that fitness pros apply reverse pyramid and linear pyramid protocols with a variety of loads (see the sample program, below).

See also: High-Intensity Functional Resistance Training for Older Adults

6. Cluster-Set Training

What Is It?

Introduced in 1987 by Roll and Omer at Tulane University, cluster sets are unique resistance training techniques where lifters take a short rest interval within the set of any given exercise (Davies et al. 2021). For example, when performing a cluster set with an 8-RM, the lifter would perform the first four repetitions, rest for 20–30 seconds, and then perform the final four repetitions.

In contrast, when performing traditional RT with an 8-RM, the lifter would perform 8 consecutive repetitions without any rest during the set. Cluster sets are advantageous because they minimize fatigue incurred during a set of RT and provide a lower perceived exertion to the lifter (Davies et al. 2021).

The Science

Davies and colleagues recently completed a meta-analysis and systematic review that compared the effects of chronic (>3 weeks) cluster-set training to traditional set training. They found that both training styles produced similar improvements for all measured outcomes: muscular strength, power output, movement velocity, muscle hypertrophy and endurance.

Importantly, the analysis showed that there are potential differences between types of cluster-set training. For example, cluster sets of >10 seconds of inter-repetition rest, or 30–45 seconds of rest between sets may be more beneficial for the development of strength and power phases of training. Cluster sets with limited rest, such as 15 seconds of rest between sets with higher repetitions, enable greater training volumes for probable muscular endurance applications. Additionally, study results indicate that the same muscular adaptations can be achieved while fatigue is minimized, making cluster-set configurations less stressful, which will be advantageous to many clients.

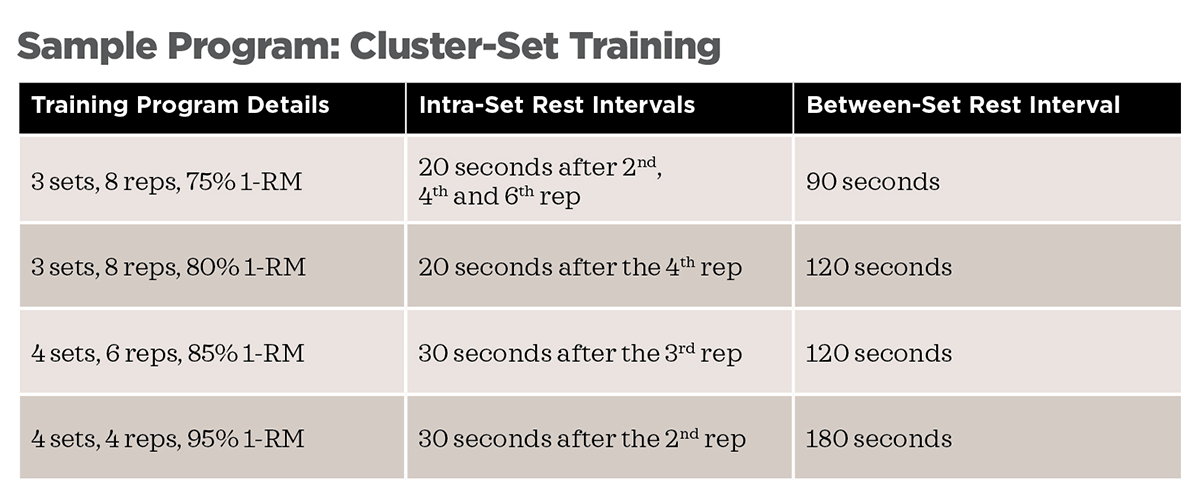

Sample Programming

We recommend that fitness pros use cluster-set training when their clients train with high volume and intensity. Specifically, the additional rest during these cluster sets will allow the lifter to perform more repetitions with higher intent, focus and velocity, which will positively affect their power and strength. Also, because cluster sets minimize fatigue and discomfort during training sessions, we recommend using cluster-set training for lesser-trained clients, as this might help them adhere better to their RT program (see the sample program, below).

7. Varying the Exercises

What Is It?

In a fixed-exercise program, a lifter would perform the same exercise for the same muscle group during training sessions (e.g., barbell deadlift would be the primary hinge exercise). However, during a varied-exercise program, the lifter would perform a variety of exercises for the same muscle group for various training sessions (e.g., rotating a barbell deadlift, trap-bar deadlift and dumbbell Romanian deadlift in training sessions). The latter allows clients to explore a variety of movement patterns and exercises.

The Science

Baz-Valle et al. (2019) assigned 19 RT-trained men (average age 23) to 8 weeks of RT while using a fixed- or rotated-exercise program. Every training variable was matched between groups including intensity (6- to 12-RM), volume (three sets per exercise), frequency (4 days per week, upper/lower split), rest intervals (120 seconds) and effort (muscle failure). Exercise selection was the only variable that differed between groups, as the fixed-exercise program involved performing the same exercises every day, while subjects in the rotated-exercise program had their exercises randomly selected via a phone app.

Data revealed that both groups significantly and similarly increased in the vastus lateralis and rectus femoris muscle thickness as well as their maximal upper- and lower-body strength. Conversely, measures of perceived motivation increased only for the varied-exercise group—they enjoyed their program more.

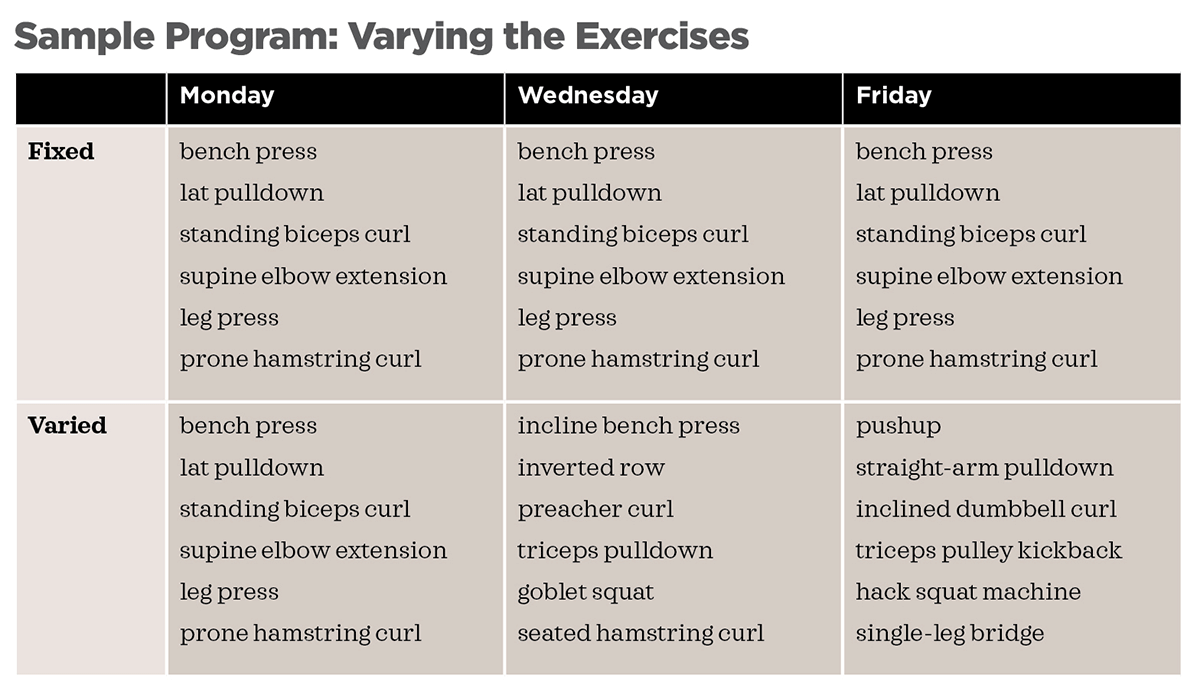

Sample Programming

To promote enjoyment, motivation and adherence, it seems important to introduce variety into a program with resistance training techniques. The manner in which Baz-Valle et al. provided variety was extreme (random selection from a phone app), and we encourage fitness pros to be more mindful with their exercise selection. We recommend introducing a variety of exercises for a muscle group/movement pattern and to cycle through them as time goes by. It may also be beneficial to provide your client with a list of 2–4 exercises for a given muscle group/movement pattern and allow them to select which exercise they would like to perform that day (see the sample program, below).

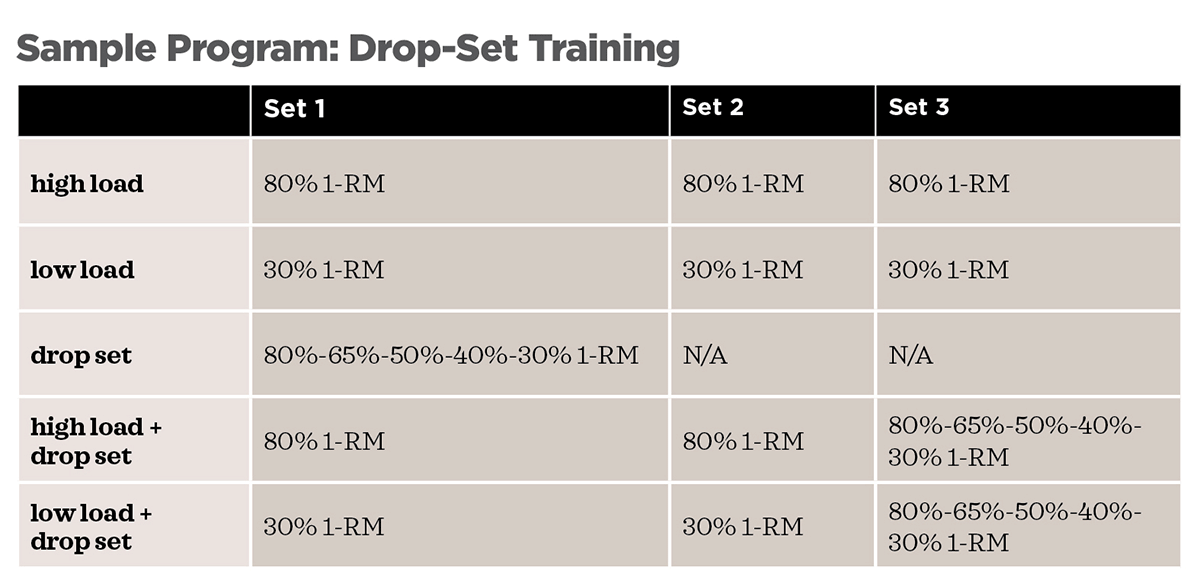

8. Drop-Set Training

What Is It?

To complete a drop set, a lifter performs an initial set to failure with a moderate-to-high external load, such as 70%–80% of 1-RM. Upon reaching failure, the external load is reduced by 20%–25% and the lifter immediately (after minimal rest, 5–10 seconds) performs a subsequent set to muscular failure (Schoenfeld & Grgic 2018).

Schoenfeld & Grgic explain that these resistance training techniques may enhance muscle growth by three contributing factors: greater metabolic stress, muscle ischemia (low oxygen to working muscle) and motor unit (single nerve and muscle fibers innervated by the nerve) fatigue. Although it is not strictly defined, most RT professionals suggest performing at least two to three drops during drop-set training bouts.

The Science

Working with nine untrained male volunteers, Ozaki et al. (2017) investigated the effects of a single high-load set (80% of 1-RM) with additional drop sets descending to a low load (30% of 1-RM) without recovery intervals on muscle strength, endurance and size.

In a very interesting re-search design, each arm was randomly assigned to one of the following three conditions: three sets of high-load resistance exercise (HL, 80% of 1-RM); three sets of low-load resistance exercise (LL, 30% of 1-RM), or a single high-load drop set with additional drop sets descending to a low load. The recovery intervals between sets were 3 minutes in the HL condition and 90 seconds in the LL condition. In the single high-load drop- set condition, participants performed a single high-load set (80% of 1-RM) and then four drop sets at 65%, 50%, 40% and 30% of 1-RM without recovery intervals between sets. It should be noted that participants performed all dumbbell biceps curl sets to concentric failure, 2–3 days a week for 8 weeks.

Data revealed that the elbow flexor muscle cross-sectional area increased similarly in all three conditions. However, the maximum isometric and 1-RM strength of the elbowflexors increased from pre to post only in the HL and single drop-set conditions. Contrariwise, muscular endurance, as measured by maximum repetitions at 30% of 1-RM, increased only in the LL and the single drop-set conditions.

The researchers concluded that with untrained males, a single drop-set training program can simultaneously increase the cross-sectional area of the target muscle and increase muscle endurance and strength in less time as compared to typical RT protocol.

Sample Programming

The use of drop sets is particularly interesting because it requires minimal training time, which allows exercise enthusiasts to accrue high levels of training volume without enduring unnecessarily long sessions. We encourage fitness pros to consider exercise selection when designing drop-set bouts (see the sample program, below). In particular, it will be more effective and safer to perform drop sets on machine-based exercises, especially those that have weight stacks.

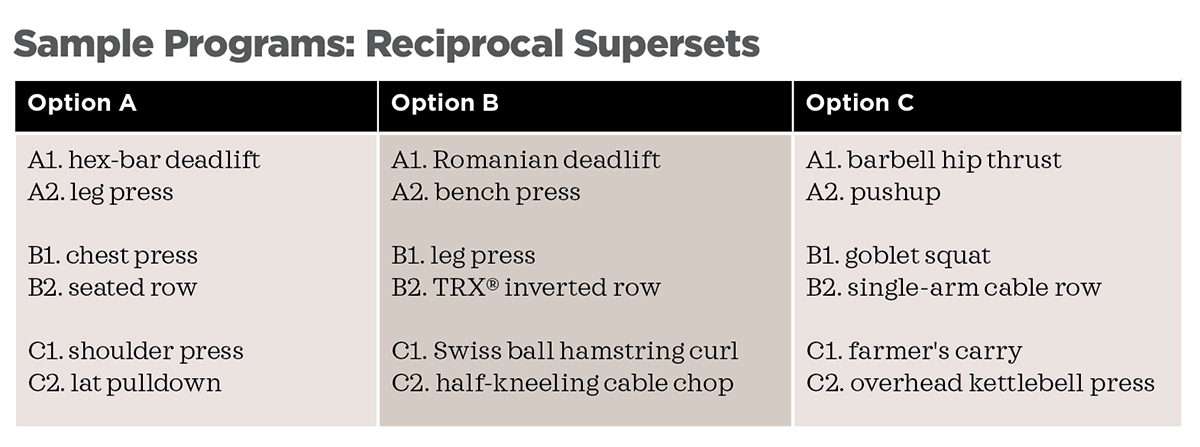

9. Reciprocal Supersets

What Is It?

Reciprocal supersets, also known as paired or agonist-antagonist sets, consist of performing two consecutive exercises of opposing muscle groups with minimal rest between them. The rest interval is provided after the superset.

For an upper-body example, a lifter might execute 10–15 reps of a “push” movement (e.g., bench press) immediately followed by 10–15 reps of a “pull” movement (e.g., seated row), and then take a 90-second rest. Due to the brief periods of rest between exercises of opposing muscle groups, total training time is reduced, which makes reciprocal super-set training one of the best time-efficient resistance training techniques to elicit muscular adaptations.

The Science

Recently, Realzola et al. (2021) compared the effect of reciprocal superset versus traditional-set training on metabolic stress and cardiovascular strain in 18 resistance-trained females and males (average age 23). For their study, the hexagonal bar deadlift was paired with leg press, chest press was paired with seated row, and overhead dumbbell press was paired with latissimus dorsi pulldown. Participants completed four sets of 12–15 repetitions for each exercise (each superset consisted of 24–30 reps). The rest between each pair was minimal, and 90- to 120-second rest intervals took place after each superset.

Compared with traditional-set training, reciprocal supersets led to higher heart rate, oxygen uptake, EPOC (excess postexercise oxygen consumption, or the exercise afterburn), RPE and blood lactate, while training time was much shorter (26.7 minutes versus 45.6 minutes).

Sample Programming

Reciprocal supersets are time-efficient resistance training techniques to perform high RT volume without spending hours in the gym. We encourage fitness pros to perform true agonist-antagonist supersets (Option A in the sample programs, above). or to mix and match upper- and lower-body supersets. Following the options shown in the sample program, perform paired exercises (A1 and A2) with minimal rest, in between and then rest for 90–120 seconds. Repeat A1 and A2 for 3–4 rounds before moving on to the next superset (B1 and B2).

See also: Tapering for Resistance Training: Less Is More!

10. Pre-Exhaustion Training

What Is It?

Pre-exhaustion training involves performing a single-joint exercise (e.g., leg extension) to near fatigue prior to completing a multijoint exercise that includes the same muscle (e.g., leg press). This timesaving style of training is generally implemented by combining two or more consecutive exercises that stress the same muscle group with minimal to no rest between exercises (≤10 seconds). It is thought that by eliciting fatigue before the multijoint exercise, there is an increase in neural drive and consequently muscle activation during the multijoint exercise. Over time, sets performed with higher neural drive and muscular activation may maximize strength and hypertrophic outcomes (Trindade et al. 2019).

The Science

In a recent study, Trindade and colleagues assigned 31 healthy men to one of three groups: traditional exercise, pre-exhaus-tion training or nonexercise (control). The traditional group performed the 45-degree leg press at three sets to failure at 75% of 1-RM with 1 minute rest between sets on 2 days a week for 9 weeks. The pre-exhaustion group completed a set of leg extensions at 20% of 1-RM to failure immediately (≤10 seconds) before the leg press. The researchers observed no significant difference between these two groups regarding changes in muscular strength or hypertrophy.

Sample Programming

The research by Trindade et al. demonstrates that pre-exhaustion and traditional resistance training techniques are equally effective, and we recommend that fitness pros use both in their programs. Pre-exhaustion training can provide a unique stimulus for a lifter who feels like they have reached a training plateau or for a client who has a specific training goal, such as increased hypertrophy of biceps or deltoids.

There are several applications of pre-exhaustion training (see the sample program, below). First, a lifter can fatigue the target muscle with a single-joint exercise (e.g., knee extension) before using the same muscle during a multijoint exercise (e.g., leg press). Next, a client can fatigue a synergist muscle with a single-joint exercise (e.g., triceps extension) to place more demand/stress on a prime mover during a subsequent multijoint exercise (e.g., chest press). Last, a lifter can perform a multi-joint exercise (e.g., seated row) before a single-joint exercise (e.g., biceps curl) where the target muscle is pre-exhausted during the first exercise and then isolated in the second exercise.

Final Thoughts on Resistance Training Techniques

As we progress into this next chapter of COVID-19 opportunities, fitness pros now have 10 advanced, evidence-based resistance training techniques to incorporate with client programs. Perhaps now is also the time to affirm and proclaim our unified lifting philosophical slogan, “with every repetition, we all get stronger and healthier.”

References

Baz-Valle, E., et al. 2019. The effects of exercise variation in muscle thickness, maximal strength and motivation in resistance trained men. PLOS ONE, 14 (12), e0226989.

Bennie, J.A., et al. 2020. Trends in muscle-strengthening exercise among nationally representative samples of United States adults between 2011 and 2017. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 17, 512–18.

Davies, T.B., et al. 2021. Chronic effects of altering resistance training set configurations using cluster sets: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Medicine, 51, 707–36.

Goto, M., et al. 2019. Partial range of motion exercise is effective for facilitating muscle hypertrophy and function through sustained intramuscular hypoxia in young trained men. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 33 (5), 1286–94.

Kojic, F., et al. 2021. Effects of resistance training on hypertrophy, strength and tensiomyography parameters of elbow flexors: Role of eccentric phase duration. Biology of Sport, 38 (4), 587–94.

Krzysztofik, M., et al. 2019. Maximizing muscle hypertrophy: A systematic review of advanced resistance training techniques and methods. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16 (4897).

Ozaki, H., et al. 2017. Effects of drop sets with resistance training on increases in muscle CSA, strength, and endurance: A pilot study. Journal of Sports Sciences, 36 (6), 681–96.

Razmjou, S., et al. 2010. The effects of Delorme and Oxford techniques on serum cell injury indices and growth factor in untrained women. World Journal of Sport Sciences, 3 (1), 44–52.

Realzola, R.A., et al. 2021. Metabolic profile of reciprocal supersets in young, recreationally active women and men. The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, Accessed Dec. 31, 2021: doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000003920.

Schoenfeld, B., & Grgic, J. 2018. Can drop set training enhance muscle growth? Strength and Conditioning Journal, 40 (6), 95–98.

Schoenfeld, B.J., & Grgic, J. 2020. Effects of range of motion on muscle development during resistance training interventions: A systematic review. SAGE Open Medicine, 8, 1–8.

Tanimoto, M., et al. 2008. Effects of whole-body low-intensity resistance training with slow movement and tonic force generation on muscular size and strength in young men. The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 22 (6), 1926–38.

Trindade, T.B., et al. 2019. Effects of pre-exhaustion versus traditional resistance training on training volume, maximal strength, and quadriceps hypertrophy. Frontiers in Physiology, 10 (1424).

Wackerhage, H., et al. 2019. Stimuli and sensors that initiate skeletal muscle hypertrophy following resistance exercise. Journal of Applied Physiology, 126, 30–43.

Len Kravitz, PhD

Len Kravitz, PhD is a professor and program coordinator of exercise science at the University of New Mexico where he recently received the Presidential Award of Distinction and the Outstanding Teacher of the Year award. In addition to being a 2016 inductee into the National Fitness Hall of Fame, Dr. Kravitz was awarded the Fitness Educator of the Year by the American Council on Exercise. Just recently, ACSM honored him with writing the 'Paper of the Year' for the ACSM Health and Fitness Journal.

Zachary Mang, PhD

Zachary Mang, PhD, is a postdoctoral research associate for the wellness program at the Los Alamos National Lab where he specializes in strength and conditioning for structural firefighters. His research interests include resistance training for hypertrophy, oxidative adaptations to resistance training, and the use of resistance training as a frontline defense to prevent chronic disease.

Jeremy Ducharme

Jeremy Ducharme, is a doctoral student in the exercise science program at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque, where he works as a teaching and research assistant. His research interests include exercise amongst older adults, and specifically assessing maximal oxygen consumption and adaptations from resistance training in this population.