Water Workouts Make a Splash

Is water walking as effective as land walking for better health? Yes!

| Earn 1 CEC - Take Quiz

Why Water Workouts?

Why are water workouts worth diving into? Science has established that low cardiorespiratory fitness is an independent predictor for cardiovascular disease and all causes of mortality (Haynes et al. 2020). Haynes and colleagues cite research indicating that a 1 MET improvement in aerobic capacity has been shown to result in a 15% decrease in mortality from cardiovascular disease. (1 MET = 3.5 milliliters of oxygen consumed per kilogram of body weight per minute.) For certain populations, such as older adults, however, you may need to adjust land exercises that improve aerobic capacity to avoid musculoskeletal injury. Haynes et al. propose that, to be optimal for older adults, exercise recommendations must focus on maximizing benefits while minimizing risks.

Enter water-based workouts. Water-based exercise programs are a good option for older populations and those with elevated injury risk. That’s because of the lower gravitational forces and reduced impact on the skeletal system. Nonetheless, there’s very little long-term data on how cardiorespiratory fitness and body composition are affected by water walking versus land walking (at the same relative intensity).

Australian research teams Haynes et al. and Naylor et al. (2020) investigated this topic in a single study. Their findings are published in two publications.

Haynes, A., et al. 2020. Land-walking vs. water-walking interventions in older adults: Effects on aerobic fitness. Journal of Sport and Health Science, doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2019.11.005.

Naylor, L.H., et al. 2020. Land- versus water-walking interventions in older adults: Effects on body composition. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 23, 164–70.

Study Overview

The researchers recruited 72 older men and women volunteers (average age = 62). Participants were assigned to 6 months of water walking, land walking or no additional activity (the control group). Investigators tested maximal aerobic capacity and body composition change as the main outcome variables, and they measured these at the beginning of the study and after the 24-week intervention. They hypothesized that water walking and land walking would improve aerobic fitness and body composition similarly and would be more beneficial than no intervention.

Study Thesis

In water walking, the lower limbs work against the resistance of water. That’s important because balance and fall prevention are often concerns for exercising men and women as they age. The water workout environment minimizes the risk of falls and possible joint injury. Therefore, if water walking is as efficacious for health as land walking is, then walking in water is a safe option for many older participants—and those at risk of falls—to consider.

Participants

Inclusion criteria for participants were that they were

- ≥ 50 years old and relatively inactive (< 60 minutes of purposeful physical activity per week);

- nonsmokers (for > 12 months prior to the study);

- light drinkers (alcohol intake less than 280 grams per week); and

- had no injuries, illnesses or diseases (i.e., cardiovascular disease, diabetes, stroke or heart attack) that would forbid study participation.

The women in the study were all postmenopausal.

Those meeting these criteria underwent a university physical exam to meet other target criteria, including

- a body mass index < 40;

- resting blood pressure of < 160 millimeters of mercury systolic and < 100 mm Hg diastolic;

- fasting blood cholesterol < 7 millimoles per liter; and

- urea and creatinine levels that ruled out the presence of abnormal kidney function.

See also: The Latest in Water Fitness: Research Update

Water Workout Exercise Intervention

Researchers randomly assigned participants to a water walking, land walking or inactive control group. There were three supervised exercise sessions per week for the water walking and land walking. The water walking took place in chest-deep (reaching xiphoid process) water at a university pool (20 meters wide x 30 meters long) heated to 28–30 degrees Celsius (82–86 degrees Fahrenheit). The land walking took place on flat, paved ground and grass terrain outdoors, in and around the university grounds.

Exercise intensity, based on the VO2max pre-test, was initially 15 minutes at 40%–45% of heart rate reserve (HRR) and progressed to 50 minutes at 55%–65% HRR over the course of the study. Session 2 of each week was an interval workout with 1-minute work intervals at that week’s specified intensity alternating with 30 seconds of rest.

Over the 24 weeks, the interval workout changed to 2-minute work intervals (at the week’s specified intensity) alternating with 2-minute recovery intervals. Trainers monitored heart rates continuously and recorded them every 5 minutes. They adjusted walking speed to match the intensities of the water walking and land walking. All sessions included a light aerobic, dynamic range-of-motion warmup and concluded with a cooldown. The team instructed the control group participants not to change their pre-study physical activity during the study.

Testing

The study used a graded maximal-effort treadmill test, conducted in 3-minute increments, with 12-lead ECG monitoring to assess maximal aerobic capacity at the start and after the 24-week intervention. The team took waist and hip measurements to determine BMI and used dual X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) to ascertain body segment and whole-body fat and lean tissue values, as well as android (abdominal) and gynoid (hip) regional fat areas.

Results and Discussion

The water-walking group showed a significant improvement in lower-limb lean mass.

Of the 72 original participants, one withdrew from the study during the 6-month period. Thus, researcher conducted data analysis on 71 volunteers. One interesting extra measure the researchers took was to collect post-study data on the main variables at 48 weeks. Between week 24 and week 48, participants had no required contact with the researchers. Participants were free to exercise or not exercise, as they chose.

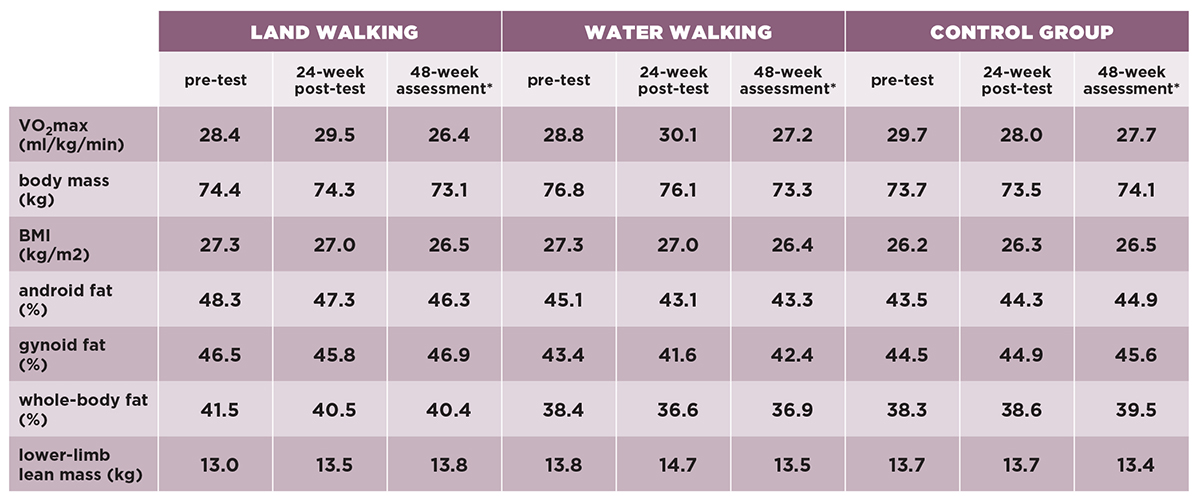

Data for the main outcome variables at pre-test and at 24 and 48 weeks is shown in “Aerobic Performance and Body Composition Results,” below.

The VO2max values significantly increased in the land-walking and water-walking groups as compared with the control group. Maximal aerobic capacity improved equally in both exercise groups. Also, researchers saw a critical, statistically significant difference in body composition in the percentage of android fat.

The two walking groups made a significant (and equal) decrease in android fat as compared with the control group. Android adiposity, also called visceral fat, is characterized by intra-abdominal fat. This fat pattern is associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, type 2 diabetes and insulin resistance (Okosun, Seale & Lyn 2015). Researchers did not observe other differences in body mass, BMI or body fat.

Interestingly, the water-walking group showed a significant improvement in lower-limb lean mass (muscle) as compared with the control group. Researchers did not observed this in the comparisons of the land-walking group to the control group. Haynes et al. propose that water walking may offer a combination of aerobic and resistance exercise.

See also: Mindful Exercise in the Pool

Water Workouts: Take-Home Messages

This is perhaps the longest, most well-designed training study ever conducted on water walking. It shows that the cardiorespiratory and body composition benefits of this type of exercise are equal to those of land walking at the same intensity.

Importantly, both walking groups progressed to moderate-intensity steady state and interval-training workouts during the 6-month study. And both walking groups saw a significant (and positive) decrease in visceral fat, the fat pattern associated with major diseases (i.e., cardiovascular disease, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, type 2 diabetes and insulin resistance).

Naylor et al. highlight that aging is associated with a decrease in muscle mass and an increase in fat mass. However, with water walking showed an increase in lower-limb muscle mass and a decrease in abdominal body fat. Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry was most beneficial for determining precisely where body composition changes were taking place. The 48-week data, based on participants self-selecting whether to continue the exercise program on their own after 24 weeks, indicated that compliance may have been dipping.

These findings suggest how important fitness pros can be in motivating older clients to maintain their exercise programs. It provides an effective option that minimizes some of the risks of land-based interventions. The evidence is powerful: Water workouts really do provide an effective “splash.”

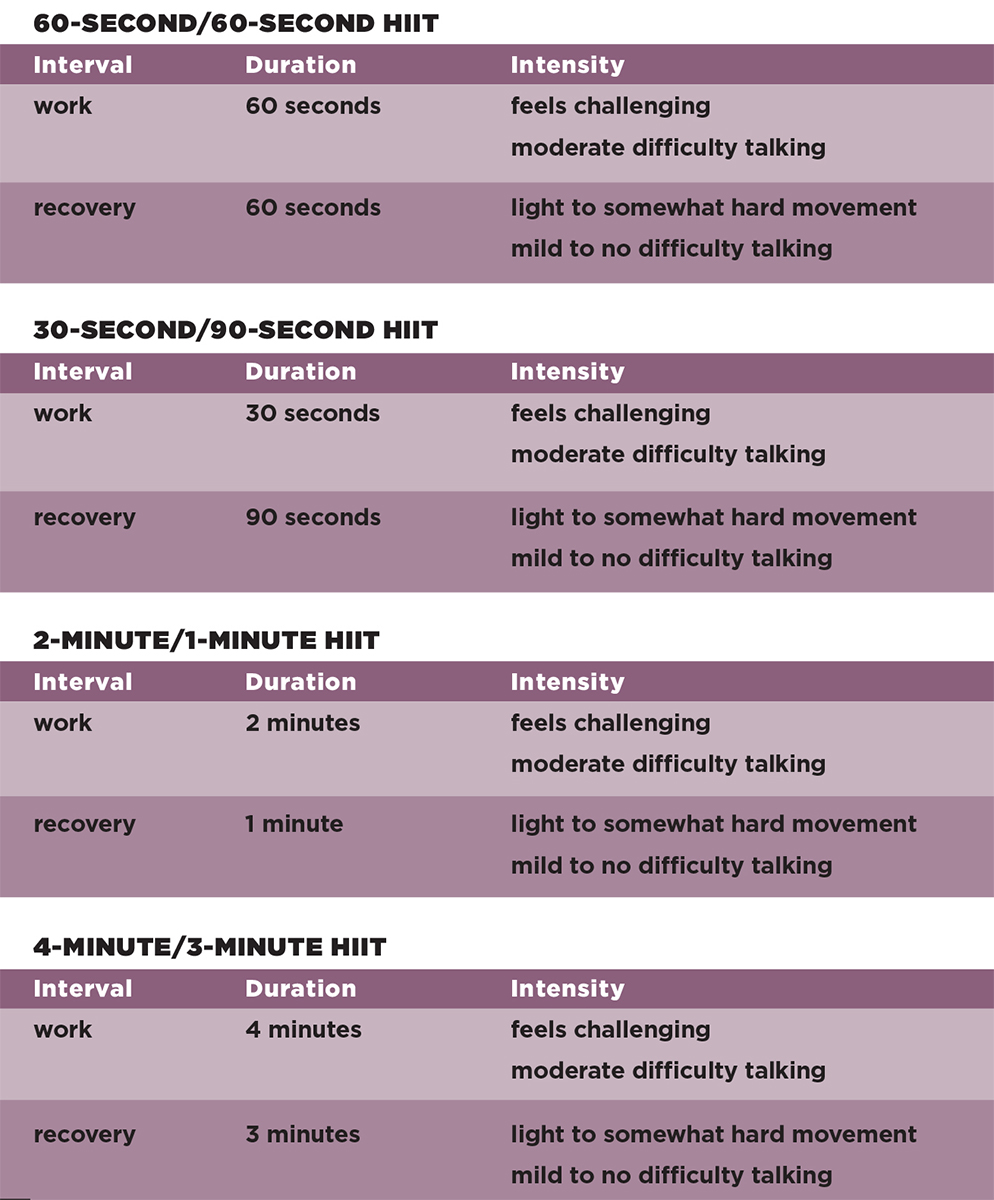

Water-Walking and Land-Walking HIIT

In addition to the two HIIT workouts described in this research, here are four additional walking HIIT workouts. The title of each program indicates its work-recovery ratio in seconds or minutes. Fitness pros should design a workout that is appropriate in length for the client’s fitness level and health. Subjective intensity monitoring is shown. Each workout should include a warmup and a cooldown.

Source: Kravitz, L. 2018. HIIT Your Limit. NY: Apollo Publishers.

Aerobic Performance and Body Composition Results

Sources: Haynes et al. 2020, Naylor et al. 2020.

*Between the 24-week post-test and the 48-week assessment, participants exercised on their own, as they wished. There were no official interactions with the researchers during that period.

References

Okosun, I.S., Seale, J.P., & Lyn, R. 2015. Commingling effect of gynoid and android fat patterns on cardiometabolic dysregulation in normal weight American adults. Nutrition & Diabetes 5, e155.

Len Kravitz, PhD

Len Kravitz, PhD is a professor and program coordinator of exercise science at the University of New Mexico where he recently received the Presidential Award of Distinction and the Outstanding Teacher of the Year award. In addition to being a 2016 inductee into the National Fitness Hall of Fame, Dr. Kravitz was awarded the Fitness Educator of the Year by the American Council on Exercise. Just recently, ACSM honored him with writing the 'Paper of the Year' for the ACSM Health and Fitness Journal.