Understanding the Glycemic Index

This method of ranking different foods by blood glucose response may help battle obesity and serious diseases.

Long the subject of controversy among nutrition experts, the glycemic index (GI) has been making news lately in the consumer press. The subject of several recent studies, this numerical method of classifying foods appears to be gaining favor as a tool in the fight against obesity and certain life-threatening medical conditions.

Although more research is needed, many nutrition experts have come to recognize that the GI is a reliable way to help consumers make healthier food choices. As this method gains more attention, your own clients may ask you questions about the GI. Reading this article could help you formulate answers to those questions.

The Background

Developed 20 years ago by researchers at the University of Toronto, the GI was created to help diabetics make good food selections in order to manage their chronic condition. In developing the GI, the researchers questioned the conventional wisdom at the time that all carbohydrates produce the same effect on blood sugar levels. Although earlier studies had cast doubt on this “wisdom,” it continued to be the cornerstone of ongoing diabetes education (Brand-Miller et al. 1996).

To further diabetes education, the researchers devised the glycemic index, which ranks different foods based on their immediate effects on blood sugar, or how quickly or slowly different types of carbohydrate affect blood sugar levels compared to other foods. Glycemic index is also the term applied to the individual GI value of a given food. The lower a food’s GI, the slower an individual’s blood glucose response is to that food. The purpose of the GI rankings is to help people focus on those foods that produce a slow, steady rise in blood sugar, resulting in stable blood glucose levels. This, in turn, affects energy and hunger levels in a positive way, keeping energy up and hunger at bay. (Conversely, sharp highs and crashing lows in blood glucose levels can cause energy levels to drop and hunger to increase, causing people to overeat.)

Foods with low GIs can produce greater satiety (the sensation of feeling full), which is crucial for weight control. Low-GI foods can also lead to improved insulin sensitivity and lower blood lipid concentrations, both associated with reduced risk of cardiovascular disease and improved diabetes management.

Measuring a Food’s GI

Put simply, the GI compares equal amounts of available carbohydrate in different types of foods. A strict testing protocol is used to determine the GI of any particular food. First, a subject’s blood glucose response to 50 grams (g) of available carbohydrate in the “test food” is measured and plotted on a graph. This value is compared to the same subject’s blood glucose response to 50 g of available carbohydrate in pure glucose or white bread (known as the “reference food”); this second value is indexed, or plotted, on the same graph. The data from the two emerging lines on the graph are then calculated using a computer program. Next, this same procedure is conducted on eight to 10 additional subjects and on several different days, and the average GI for the test food is calculated based on all the data collected.

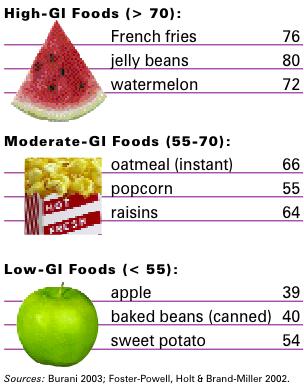

The GI is scored on a numeric scale of 1 to 100. Low-GI foods have scores below 55; moderate-GI foods have scores of 55 to 70; and high-GI foods have scores above 70.

Putting Things Into Perspective

It’s important to realize that many factors can influence a food’s GI. In fact, the same food can have a higher or lower GI score depending on its ripeness (e.g., the riper a banana, the higher its GI) or how it is cooked.

Here is a partial list of the factors that can affect the GI of any food:

- physical and chemical characteristics

- rate of carbohydrate digestion

- type of flour (if any) contained in the product

- moisture content

- cooking time and method

- degree of ripeness

- other ingredients or processing methods used by food manufacturers

The Role of Glycemic Load

The GI is just one tool to help clients make sound food choices. Some nutrition experts say that because people eat meals, not singular foods, the glycemic load (GL) should be considered in conjunction with the GI.

Although the terms are similar, the two tools differ as follows: The GL reflects the amount of available carbohydrate in a typical serving size of a particular food. The GI measures a fixed amount (50 g) of available carbohydrate in that food—usually far more than most people would eat in one sitting. For example, the glycemic load of one slice of bread would be more representative of a typical serving size than the bread’s glycemic index, which would be based on 3 1/2 slices in order to measure 50 g of available carbohydrate.

A food’s GL is arrived at by multiplying the amount of available carbohydrate in a typical serving size by the food’s GI and dividing the result by 100. For example, for oil-popped popcorn (a moderate-GI food), a typical serving size is 2.6 cups, or 1 ounce; the amount of available carbohydrate is 16 g; and the GI is 55 (Pennington 1998). The GL for this food is therefore

16 × 55 ÷ 100, which equals 8.8, or 9.

GI & Disease Management

Obesity, diabetes and cardiovascular disease (CVD) are three conditions in which GI may play a significant, positive role in both treatment and prevention. Positive associations have also been shown between GI and certain types of cancer, specifically colon and breast cancer, although more studies are needed in this area.

Here’s a look at some recent findings on how GI relates to obesity, diabetes and CVD.

Many experts believe that staving off hunger is critical to weight management. Often, dieters reach for low-fat or fat-free processed foods with high GIs. However, such foods—by producing a high glycemic response—increase insulin levels and hunger.

Replacing these foods with low-fat, low-GI foods will produce a low glycemic response, which minimizes insulin secretion, helps maintain insulin sensitivity and promotes higher satiety. Additionally, eating a diet rich in low-GI foods decreases the desire for processed foods, which tend to have minimal nutritional value but lots of calories.

Low-GI foods, such as whole grains, legumes and most fruits and vegetables, are naturally low in fat and contain complex carbohydrates and significant amounts of fiber. High-fiber foods contribute to feelings of fullness and satisfaction and can therefore help clients adhere to a healthy eating plan. Although human studies to date have shown mixed results regarding the relationship between low-GI foods and weight loss, clients who use the GI as a guide for carbohydrate selection may see some benefit in this area.

Whether diabetes can be prevented by following a low-GI diet is another area of controversy. Researchers have long theorized that a long-term high intake of carbohydrates increases the risk of type 2 diabetes, owing to either insulin resistance or pancreatic exhaustion (Willett, Manson & Liu 2002). Although not conclusive, the findings of other studies suggest that diets composed mainly of high-GI/GL, low-fiber foods can increase the risk of type 2 diabetes (Jenkins et al. 2002).

Where the scientific evidence is more convincing is in the effect that GI has on the treatment and management of diabetes. Selecting low-GI foods and spacing carbohydrate choices throughout the day in different meals and snacks have been shown to help control blood sugar levels (Jenkins et al. 2002).

Traditionally, dietary intervention for CVD has been a low-fat, high-carbohydrate diet. An overall reduction in total fat normally elicits a reduction in saturated fat, which is essential for managing CVD. However, upping consumption of carbohydrate foods, particularly those with high GIs, may have a negative effect on blood lipids by increasing total cholesterol, LDL (“bad”) cholesterol and triglycerides and decreasing HDL (“good”) cholesterol.

Recent research has shown that substituting low-GI foods for high-GI items, while still maintaining a low-fat, high-carbohydrate diet, has a positive effect on lipid profiles (Pelkman 2001).

Putting the GI Into Practice

Understanding all the implications of the GI can be a challenge, one that is outside the scope of practice for fitness professionals. But, in order to answer client questions, be aware of the following real-world applications of this important nutrition tool:

- The GI was not designed to reduce the total amount of carbohydrates people consume in their diet, but instead to help individuals choose the types of carbohydrates that evoke a slower insulin response.

- People should focus more on GI food categories, rather than on the specific value of any one particular food.

Select foods from the low and moderate

categories more often than from the high category.

- Remember that foods are typically eaten in combination with other foods. Toppings, spreads, dressings, sauces and other foods can all influence the effect of carbohydrate on blood glucose, as can food ripeness, cooking time/method and other factors.

- Replacing one high-GI food with one low-GI food at each meal or snack is a simple way to reduce glycemic response. (And it is more realistic than totally abstaining from any one food.)

- Stress to clients that small amounts of high-GI foods can be part of a well-balanced diet. But remind them that the higher the GI is, the smaller the portion should be!

- High-GI foods may be helpful immediately after a hard workout, to replenish glycogen stores. Conversely, clients would be better off eating low-GI foods before exercising, to enhance a steady energy release.

- The GI should not be used in isolation. Equally important to a healthy diet are a food’s GL, the amount of calories/fiber/

micronutrients consumed and meal timing. These are all areas in which a registered dietitian can provide expert and individualized guidance.

Instead of focusing too much on the GI of any one particular food, clients would do well to select foods from the low and moderate categories more often than from the high category. Note that values shown are rated on a numeric scale of 1 to 100.

www.glycemicindex.com: Offers a GI database, along with information on the GI testing procedure.

www.mendosa.com: Lists the GIs for many common foods.

www.diabetes.ca/Section_About/glycemic.asp: Offers an in-depth look at the GI, from the Canadian Diabetes Association.

References

Brand-Miller, J., et al. 1996. The Glucose Revolution. New York: Marlowe & Company.

Foster-Powell, K., Holt, S.H.A., & Brand-Miller, J.C. 2002. International table of glycemic index and glycemic load values: 2002. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 76 (1), 5-56.

Jenkins, D.J.A., et al. 2002. Glycemic index: Overview of implications in health and disease. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 76 (Suppl.), 266S-73S.

Pelkman, C.L. 2001. Effects of the glycemic index of foods on serum concentration of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and triglycerides. Current Atherosclerosis Reports, 3 (6), 456-61.

Pennington, J.A.T. 1998. Bowes & Church’s Food Values of Portions Commonly Used. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Willett, W., Manson, J., & Liu, S. 2002. Glycemic index, glycemic load and risk of type 2 diabetes. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 76 (Suppl.), 274S-80S.