Lessons From the Blue Zones

What we can learn from the world’s longest-living people.

Is there a formula for longevity? Researchers are looking for clues in the “blue zones,” locations around the globe where people live measurably longer than in the rest of the world. Dan Buettner, explorer and author of the best-selling book The Blue Zones: Lessons for Living Longer From the People Who’ve Lived the Longest (National Geographic 2008), believes that the blue zones have much to teach us about how to live longer, better lives.

“In these blue zones we found people who reach age 100 at rates 10 times greater than in the United States; where people suffer a fraction of the rate of heart disease and cancer [that] we do; and where people are getting the extra 10 years that we’re missing,” says Buettner. His groundbreaking work on longevity led to his 2005 National Geographic cover story, “Secrets of Living Longer,” which was a finalist that year for the National Magazine Award. He has appeared on CNN, David Letterman, Good Morning America, Primetime Live, Today and Oprah.

Longevity Hot Spots

The four blue zones identified in Buettner’s book are Okinawa, Japan; Sardinia, Italy; the Nicoya Peninsula of Costa Rica; and Loma Linda, California. Working with National Geographic, Buettner and teams of scientists have identified longevity pockets around the globe and traveled there to examine the lifestyle characteristics that may contribute. Buettner’s book details his entertaining experiences and discussions with vibrant and healthy elderly people in the blue zones.

Here’s a brief look at what Buettner and his team of researchers found in the blue zones:

Sardinia. On this Italian island, the typical Sardinian diet contains beans, whole-grain breads, fruits, garden vegetables, goat’s milk, moderate amounts of red wine and, in some parts of the island, mastic oil, which is derived from an evergreen shrub. Sardinians often walk at least 5 miles a day. The culture emphasizes humor and laughter, and places high value on the elderly and family. The rate of centenarians in Sardinia is extraordinary—about 30 times higher than the rate in America. And unlike in other parts of the world, where women more frequently live to 100, men and women in Sardinia reach 100 at a roughly equal rate.

Okinawa. Across this collection of sunny islands, the diet is primarily vegetarian and includes stir-fried vegetables, tofu, miso, sweet potatoes and goya, or “bitter melon.” Older Okinawans typically garden daily, growing mugwort, ginger, turmeric and fresh vegetables and herbs. They are active walkers, maintain strong social circles and emphasize a life purpose or “ikigai.” Okinawans reach the age of 100 at a rate three times higher than Americans, have about one-fifth the rate of heart disease and live about 7 good years longer, says Buettner.

Loma Linda. In this Seventh Day Adventist community, diet and health are closely tied to religion, and Adventists tend to stay active, follow a vegetarian diet, snack on nuts, eat a light dinner, drink plenty of water and maintain healthy body mass indexes. Adventists observe a weekly day of rest and emphasize social support and volunteerism. This is America’s longest-lived culture, where lifespan is about a decade longer than for most Americans.

Nicoya Peninsula. According to blue zones demographers, this community in Costa Rica may have the longest life expectancy in the world. Buettner reports that, per capita, Costa Rica spends only about 15% of what America does on health care, yet its people appear to live longer than anyone else on earth. Centenarians here have a strong sense of purpose, family and community, and most have enjoyed hard physical work throughout their lives. They spend regular time in the sun and eat light dinners and a traditional diet of maize (corn) and beans.

Since writing the book, Buettner has identified a fifth blue zone, the Greek island of Ikaria. Compared with Americans, people there are three times more likely to reach age 90. They have about 20% less cancer, half the rate of cardiovascular disease and almost no dementia.

Nine Common Denominators

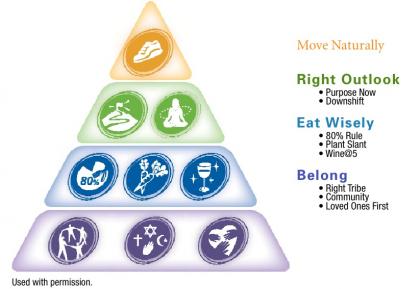

Based on the habits of blue zone populations, Buettner identifies nine lifestyle characteristics that may help you live a longer, healthier life (see Figure 1.)

- Make regular activity intrinsic to your daily routines.

- Have a “Plan de Vida,” i.e., a mission or purpose that gives meaning to your life.

- Take your life out of the fast lane: work less, slow down, rest, take vacations.

- Eat less by following the “80% rule.” (Stop eating when you’re 80% full.)

- Shift your diet to more vegetables and fruits, less protein and fewer processed foods.

- Drink red wine in moderation.

- Create a healthy social network.

- Cultivate spiritual or religious beliefs and participation.

- Make family a priority.

“We see from the blue zones and aging research in general that these behaviors are associated with longer life—and the same things that can help get you to a healthy 90 or 100 can get you there better,” says Buettner. “They don’t just add years; they’re vital, enriching years.”

But don’t quit your job just yet to move to an island of vegetarians and drink more red wine. Buettner emphasizes that his goal isn’t to force unrealistic expectations on people who don’t live in blue zones, but rather to encourage gradual “big-picture” lifestyle changes that will foster healthy habits like daily movement, natural and moderate eating, purpose-driven living and more social connection.

Buettner’s advice for fitness professionals who want to help clients live longer, healthier lives is to encourage behavior changes that go well beyond a workout. “The secret to longevity, as I see it, has less to do about diet—or even exercise—and more to do about the social and physical environment in which you live. People in the blue zones live rewardingly inconvenient lives. They walk to the store, to church and to their friends’ homes. They do their own yard work, hand-knead their own bread dough. In the case of Okinawa, for example, people get up and down off the floor—where they sit, eat and socialize—several dozen times a day. We figured they get over 100 minutes of ‘mindless’ physical activity everyday—and no heath club membership!”

Fitness pros and facilities that encourage social networking and activities shared among friends and families may be on the right track. “We know from the Framingham studies that happiness, smoking and obesity are all ‘contagious’,” notes Buettner. “If your three best friends are obese, there’s more than a 50% chance that you’ll be overweight too. People in the blue zones are either born into or proactively surround themselves with people who practice the right behaviors: people whose idea of fun is gardening, bocce ball or swimming; people who eat meat sparingly, who have faith, who are trusting and trustworthy.

“One of the reasons this is so important is that people in general just don’t stick to doing anything for very long. For example, research indicates that a very small percentage of people adhere to diets for more than 2 years. For anything to really impact your life expectancy positively, you need to do it for most of your life. Friends, unlike diets, are much more likely to be longer-term undertakings.”

Buettner believes the family and social aspects of his research may well be the most important finding. “We’ve become an increasingly isolated society. Fifteen years ago, the average American had three good friends. Now it’s two.” Contrast that with the blue zones centenarians who live in strong families and close-knit communities. Says Buettner, “Instead of [being] mere recipients of care, they contribute to the household and community. They grow gardens to provide vegetables; they continue to cook and clean. They feel motivated to get out of bed in the morning, stay active and live out a purpose.”

Your Personal Blue Zone

Of course, the real question is whether anecdotal evidence from these remote longevity pockets has practical application in a fast-paced modern world of technology, fragmented attention, family discord, economic stress, sedentary living and processed food.

Buettner believes that people can make changes in their environment to create their own “personal blue zone” to promote health and longevity.

His fond experiences with centenarians around the globe have sparked change in his own life. He says he’s cut most of the meat out of his diet, keeps a can of nuts in his office, spends more time with his kids, spends less time with ‘toxic’ people and has gone back to church.

“To a great extent, we each have control over our everyday environment,” says Buettner. “We can make changes that have a big impact. Last year, my partners and I made blue zones–inspired changes to the environment of an entire town, Albert Lea, Minnesota. We made the town more walkable and bikeable, dug public gardens, made it easier for kids to walk to school and created opportunities for people to work together to change their health habits. The results were ‘stunning,’ according to Walter Willet, MD, MPH, PhD, chair of the department of nutrition at the Harvard School of Public Health. Life expectancy for the average participant rose about 3 years and healthcare costs for city workers [were projected to decrease] by 48% [over time].”

This AARP/Blue Zones Vitality Project entailed a townwide makeover of new sidewalks and recreational paths, healthier options on restaurant menus and healthier snacks in schools, and creative ventures such as “walking school buses” to escort kids to school on foot. Newsweek (February 15, 2010) reported that the town’s healthcare claims fell by 32% in a 10-month period.

Buettner and his partners plan to do other projects like the one in Albert Lea. His research with National Geographic into blue zones around the world is also ongoing.

“There’s nothing terribly definitive about any of this,” cautions Robert Kane, MD, director of the Center on Aging and the Minnesota Area Geriatric Education Center at the University of Minnesota, who has worked with Buettner on the Blue Zones project. “There are no controls when you study a group of centenarians. These are not people with obesity, cancer, heart disease—it is not the same population that fitness professionals would typically train today, so it’s important to keep things in perspective. There’s a great deal we don’t know yet about longevity, and if we get any blinding insights, I think they’re going to come from the area of biogenetics.”

However, Kane believes that the blue zones lessons can provide useful insights for healthy living, and he collaborated with Buettner to create the Blue Zones Vitality Compass program, which helps people determine and plan healthy lifestyle changes. “Even though we don’t yet have conclusive data, we know that the messages from the blue zone communities are good ones. We do know that you get the biggest health impact from not smoking, and the next biggest impact is from reasonable diet and exercise. I think the most important lesson to draw from the blue zones is moderation. You don’t have to eat a completely Mediterranean diet or never eat meat again, but eating healthy foods in moderate amounts is a good thing to do. You don’t have to have the fitness level of an athlete—athletes generally don’t live to be centenarians. But moderate, regular exercise is a very good thing. And we know social support is important.”

In reality, for most of us not living in blue zones, our chances of living to 100 are still quite small. Lessons from the blue zones may well be as much about the quality of years as the quantity. Much of the aging process is, after all, a mystery.

“I have a family member who died recently at the age of 102,” muses Kane. “He probably would not have fit into the blue zones longevity model at all—except that he had a positive attitude. Maybe he was just lucky.”

For more information on ongoing Blue Zones research and longevity-related projects and programs, see www.bluezones.com.

References

Christakis, N.A., & Fowler, J.H.., 2007. “The spread of obesity in a large social network over 32 years.” The New England Journal of Medicine, 357 (4), 370–79. Epub: July 25, 2007.

Christensen, K., et al. 1999. A Danish population-based twin study on general health in the elderly.” Journal

of Aging and Health, 11 (1), 49–64.

Willett, W.C., & Underwood, A. 2010. Crimes of the heart. Newsweek (Feb. 15).