How to Help Golfers Improve Scores, Boost Performance, and Prevent Injuries

The key is to understand biomechanics of body rotation.

Professional golfers and amateur enthusiasts alike want to avoid injuries and improve their game. Fortunately, both goals are inherently linked: Staying injury-free enables golfers to train at a high level and to practice and compete regularly, which ultimately lets them hone their skills and elevate their performance.

Golf Biomechanics Basics

To help your golfing clients avoid injury and boost their level of play, you need to understand how two key myofascial systems—the posterior oblique system and the anterior oblique system—affect the golf swing. Here’s a quick look:

Posterior Oblique System

The posterior oblique system consists of muscles, fascia and connective tissue that run diagonally across the back of the torso and hips. Its primary muscles are the gluteus maximus and latissimus dorsi (see top left picture on page 26). Although the glutes and lats are on the torso and hips, the functional effect of the posterior oblique system extends much farther, owing to the attachment of the gluteus maximus (via the iliotibial band) below the knee and the attachment of the latissimus dorsi to the top of the arm (i.e., the humerus) (Golding & Golding 2003).

This contralateral, or cross-body, myofascial system enables a golfer to create power and force to hit the ball farther while reducing stress and averting potential injury to bony structures in the knees, hips, lower back, shoulders and arms (Chek 1994; Myers 2008).

The major function of the posterior oblique system is to assist with rotational movements. For example, when a right-handed player takes a backswing, the shoulders, arms, pelvis and torso rotate clockwise (when viewed from above) to activate this system (see top right picture on page 26) (Chasan 2002).

As these upper-body structures move into the backswing, the right foot holds firm to stabilize the lower body. However, to enable the torso to effectively rotate clockwise during the backswing, the right hip must be able to freely rotate internally in the hip socket. This mobility of the hip joint ensures that the feet remain fairly stable, creating a balanced platform while the torso rotates powerfully to achieve a full backswing (Chasan 2002).

Internal rotation of the hip/leg also enables the gluteus maximus to lengthen under tension like a stretched rubber band. The stored tension is then released to create a forceful strike at the ball during contact (Price & Bratcher 2010). Similarly, the latissimus dorsi is loaded with potential energy during a backswing when the arm moves up and away from the torso as it rotates. During the follow-through, the latissimus dorsi releases this energy (i.e., the muscle contracts) to produce power as the arm is pulled down toward the left-hand side of the body.

These rotational movements of the hip and spine ensure that the muscles of the posterior oblique system work effectively to minimize stress to joints, reducing potential for injury. The muscles also help to build coiled strength for an effective and efficient golf swing (Chasan 2002). Furthermore, they reduce injury risk after the ball is struck: The left gluteus maximus muscle and right latissimus dorsi muscle work together to decelerate the club head and slow down the counterclockwise rotation of the spine and shoulders during follow-through (Price & Bratcher 2010).

Anterior Oblique Movements

Golf swings also rely on the anterior oblique system’s adductor muscles and contralateral external obliques (Chek 1992). Like the muscles of the posterior oblique system, these tissues work in a cross-body fashion during a golf swing. The

anterior oblique system attaches to the upper and lower leg (adductors) and travels upward and diagonally across the pelvis and torso, where it attaches to the rib cage (internal obliques) on the opposite side (Myers 2008)

When a right-handed golfer takes a backswing, the left hip/leg externally rotates as the pelvis, spine and shoulders rotate clockwise (when viewed from above). As the pelvis and torso move away from the left leg, the left adductor group of muscles and right external oblique muscles lengthen under tension (see below, right). The tautness that this creates in the myofascial system reduces potential for injury to the hips, sacroiliac joint, spine, rib cage and shoulder girdle during the backswing. Releasing this tension produces a forceful downward rotation to let the golfer hit the ball farther (Bradley 2013). Once the ball is struck, the right adductors and left external obliques (on the other side of the body) lengthen to decelerate overall stress to the skeleton.

Understanding how the posterior and anterior oblique systems function, and how they directly affect the body, can help you design corrective exercise strategies to reduce the risk of injury. It will also enable you to create performance enhancement programs that exploit these two powerful systems to build strength and power in a golfer’s swing.

Optimal functioning of the posterior oblique system requires the hip/leg to internally rotate correctly while the torso rotates effectively. Peak performance of the anterior oblique system, by contrast, depends on external rotation of the hip/leg as the torso rotates. Thus, it is imperative to assess the rotational capabilities of the hip/leg and torso when working with golfers—or with any client who plays a sport that requires rotation of the hip/leg and trunk (i.e., making groundstrokes in tennis, hitting a baseball, throwing a discus, putting a shot, throwing a Frisbee disc, etc.) (Chasan 2002).

Instruct your client to lie on the floor on a mat. To assess the degree of internal rotation, ask the client to position his or her legs about 18 inches to 2 feet apart and try turning both legs inward (see above). Both legs should be able to turn in about 30–40 degrees (Cook 2010). To assess the degree of external rotation, instruct your client to turn the feet/legs outward, and note whether they can turn approximately 40–50 degrees (Petty & Moore 2002).

Instruct your client to lie on his or her back, knees bent and lifted up over the stomach, with a foam roller between the knees. (The roller minimizes discomfort for clients with lower-back issues.) Coach the client to drop the knees to the left side of the body, keeping hands and arms flat on the floor. If the right shoulder comes off the floor when the knees drop to the left, then the client lacks the ability to rotate the torso effectively to the right (i.e., clockwise). Alternatively, if the left shoulder comes off the floor as the knees drop to the right, then the client lacks the ability to rotate to the left (i.e., counterclockwise). A lack of rotation in either direction affects performance of the anterior and posterior oblique systems.

Damon Goddard, founder of AMPD Golf Fitness, has been training top–ranked PGA and LPGA golfers, like former world No. 1 player Jordan Spieth, for over 10 years. He emphasizes that his clients’ main goal is injury prevention, followed closely by performance enhancement.

Goddard uses specific assessments to analyze movement efficiency and uncover faulty biomechanics in order to guide corrective exercise protocols. He emphasizes that rotational athletes need to focus on efficiency of movement to minimize the risk of common golf injuries to the lower back, hips and shoulders.

Goddard also reminds us that to achieve better results with our clients, we must be prepared to invest a high level of commitment in their programs. “Our efforts will directly contribute to building trust with our athletes and encourage a subsequent high level of accountability from them—a sure–fire recipe for success.”

Warm up the soft tissues of your client’s anterior and posterior oblique systems by using a foam roller or massage ball (like a tennis ball) on all the major muscles around the shoulder girdle and in the legs, hips, buttocks and (front and back) torso (ACE 2010; Rolf 1989; Price 2013).

Next, introduce gentle stretching exercises to mobilize the hips, pelvis, spine, rib cage and shoulder girdle before progressing to the more dynamic exercises outlined below; they are designed specifically to stimulate and strengthen the anterior and posterior oblique systems.

Lunge With Rotation

This exercise strengthens the posterior oblique system by increasing internal rotation of the hip/leg and boosting torso rotation.

Lunge forward with your left leg, keeping your spine erect and shoulders level. As you lunge forward, reach down and gently pull your left knee toward the midline of your body while swinging your left arm behind you. As you rotate your torso, keep your left foot firmly in contact with the ground (see below). As you stand up out of the lunge, rotate your torso and arms back to center.

Progression, when a client becomes more confident: Swing the left arm behind you at shoulder height as you rotate (as though following through with a golf swing). Repeat these two movements back and forth as one continuous exercise, completing 10–15 repetitions on each side of the body. Do 2–3 sets.

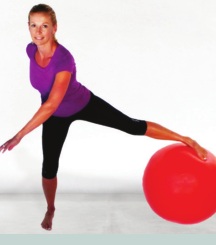

Swiss Ball Side Lunge

This exercise strengthens the anterior oblique system by increasing external rotation of the hip/leg and boosting torso rotation. Note that transferring weight onto the standing leg during this exercise also strengthens the posterior oblique system.

Place your left foot on a gym ball as you balance yourself with your right leg. Roll the gym ball out to your left side with your left foot as you perform a single-leg squat with your right leg. As you squat, rotate your arms over your right leg as though you were taking a backswing in golf. Try to keep your right knee toward the midline as you perform this movement.

Placing more weight on your left leg (on top of the ball) stresses the anterior oblique system during this movement, while putting more weight on your right leg strengthens the posterior oblique system. Perform 10–15 repetitions on each side. Do 2–3 sets.

Lying Torso Rotations

This exercise is specifically designed to increase torso rotation to strengthen the posterior and anterior oblique systems.

Lie on your back with your knees bent and positioned on the left-hand side of your body at hip height. Reach your right arm up toward the ceiling and breathe out as you drop your right arm toward the right-hand side of your body and the floor, squeezing your knees together to prevent your hips/legs from moving. Return to the starting position and perform 10–12 repetitions on each side. Do 2–3 sets.

Note: If you feel uncomfortable performing this exercise, place a foam roller or pillow between your knees to make it easier until your body has adapted to the new movement.

Many golfers find it easier to adjust their foot position to help with their backswing and/or follow-through (Woods 2001). This is usually because another part of their kinetic chain—higher up (in the hips or spine)—cannot rotate. For example, a right-handed player might compensate by turning his right foot out slightly because he cannot internally rotate his right hip during the backswing.

Manipulating the stance like this may be an effective short-term strategy for reducing injury risk during a golf swing. However, the ultimate goal should be to achieve optimal movement mechanics so that correct foot position is not compromised.

All sports that require power to forcefully hit a ball or throw an object require rotation of the major structures of the body. Understanding how to assess clients’ rotational capabilities and other movement imbalances (and knowing the soft-tissue structures involved) will help you design successful corrective exercise strategies for athletes of any skill level.

References

ACE (American Council on Exercise). 2010. ACE Personal Trainer Manual (4th ed.). San Diego: American Council on Exercise.

Bradley, N. 2013. 7 Laws of the Golf Swing. New York: Abrams.

Chasan, N. 2002. Total Conditioning for Golfers. Bellevue: Sports Reaction Productions.

Chek, P. 1992. Scientific Core Conditioning. La Jolla, CA: Paul Chek Seminars.

Chek., P. 1994. Scientific Back Training. La Jolla, CA: Paul Chek Seminars.

Cook, G. Movement. 2010. Aptos, CA: On Target Publications.

Golding, L.A., & Golding, S.M. 2003. Fitness Professional’s Guide to Musculoskeletal Anatomy and Human Movement. Monterey, CA: Healthy Learning.

Myers, T.W. 2008. Anatomy Trains: Myofascial Meridians for Manual and Movement Therapists. (2nd ed.). New York: Churchill Livingstone.

Petty, N., & Moore, A.P. 2002. Neuromusculoskeletal Examination and Assessment: A Handbook for Therapists. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone.

Price, J. 2013. The Amazing Tennis Ball Back Pain Cure. San Diego: The BioMechanics Press.

Price, J., & Bratcher, M. 2010. The BioMechanics Method Corrective Exercise Educational Program. San Diego: The BioMechanics Press.

Rolf, I.P. 1989. Rolfing: Reestablishing the Natural Alignment and Structural Integration of the Human Body for Vitality and Well–Being (revised edition). Rochester, VT: Healing Arts Press.

Woods, T. 2001. How I Play Golf. London: Little, Brown.

Justin Price, MA

Justin Price, MA, is creator of the BioMechanics Method® Corrective Exercise Specialist (TBMM-CES) program, the fitness industry’s highest-rated CES credential, with trained professionals in 80 countries. He is also the author of several books, including The BioMechanics Method for Corrective Exercise academic textbook, and he was awarded the 2006 IDEA Personal Trainer of the Year. He has served as a subject matter expert for numerous brands and media organizations including ACE, TRX® and BOSU®; the BBC, Discovery Health and MSNBC; Arthritis Today, Men’s Health, Newsweek, Time, WebMD and Tennis; and Los Angeles Times, The New York Times and Wall Street Journal. Learn more about The BioMechanics Method®