Taste Buds and Nutrition

How taste buds work and other determinants of food flavor and enjoyment.

|![]() Earn 1 CEC - Take Quiz

Earn 1 CEC - Take Quiz

Taste buds are as complex as they are underrated. For many who contracted COVID-19 and lost their facility to smell and taste, that much became clear. Though the scientific whys of both short-term and long-term loss of these senses due to the coronavirus have yet to be fully determined, having taste buds out of order proved a profound interruption in these folks’ ability to fully enjoy the many dimensions of food.

It’s one thing to not be able to pick up the amazing perfume of onions and garlic simmering or a chocolate cake baking in the oven, but it’s quite another thing to not be able to taste these flavors.

Savoring food flavors is a skill that develops over a lifetime. It takes practice as well as an open mind. Coaching clients to embrace the tastes and textures of new food and to practice mindful eating can nudge them closer to their nutrition goals with less focus on fad diets, wholesale nutrient cutting and calorie counting.

How can you help? Start by encouraging clients to reorient their mindsets about food and eating. You can guide clients on savoring and enjoying food, learning to like new tastes and textures, and incorporating cultural practices and mindfulness into their eating routines. These approaches will do more than dieting and weight loss to help your clients improve their overall nutrition, health and well-being.

A good place to start is to understand how taste buds pick up flavors and transmit them.

See also: Helping Clients Enjoy the Taste and Culture of Food

Taste Buds: Tools of Taste

The tongue, mouth and nasal cavity speed messages to the brain to help identify tastes, textures and odors. A brain region called the gustatory cortex contains thousands of neurons that respond to individual tastes.

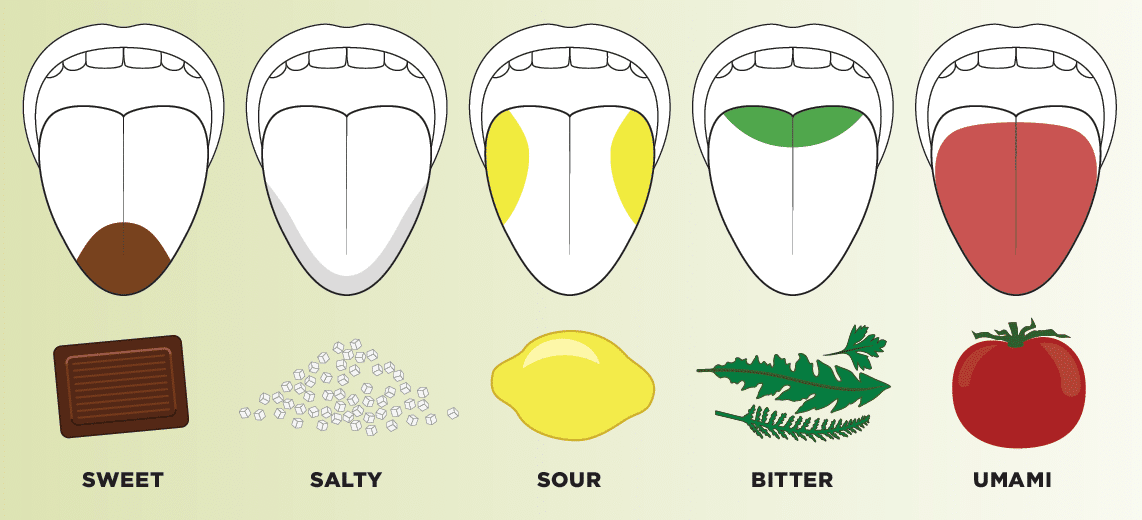

The principal tasting mechanism is the taste bud, a bundle of nerves that sense five kinds of flavors: sweet, sour, bitter, salty and umami (savory). Generally, simple carbohydrates taste sweet, the amino acids glutamate and aspartate taste savory, acids taste sour, and many toxic compounds plus some vegetables taste bitter (Breslin 2013).

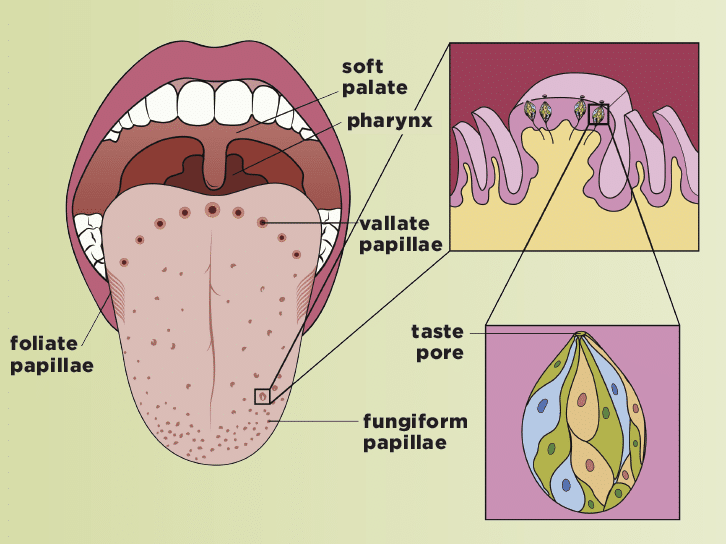

Taste buds detect flavor in three locations: the tongue’s papillae (bumps), the soft palate and the pharynx (see “Components of Taste,” below). Papillae with tasting function come in three types:

- vallate, which form an arc on the rear third of the tongue

- foliate, small slit-like bumps on the sides of the tongue

- fungiform, small bumps on the front two-thirds of the tongue

The vallate and foliate papillae contain hundreds of taste buds, while each fungiform papilla has 10–15 taste buds.

The principal tasting mechanism is the taste bud, a bundle of nerves that sense five kinds of flavors: sweet, sour, bitter, salty and umami (savory).

Taste Buds and Components of Taste

“SUPERTASTERS” VS. “NONTASTERS”

About 20% of people carry a gene that makes them “supertasters.” They have many more taste buds than average on the fungiform papillae, making this group extra-sensitive to bitter tastes, which they often find disgusting.

About 30% of people are nontasters, with far fewer taste buds than average on the fungiform papillae; this group hardly notices bitter tastes (Feeney et al. 2011).

More Factors That Influence Flavor

Texture. Filiform papillae on the front two-thirds of the tongue detect the texture of foods but have no tasting function (Breslin 2013). Most people prefer crispy, crunchy, tender, juicy and firm textures and dislike tough, soggy, crumbly, lumpy, watery and slimy textures.

Aroma. The smell center in the rear of the nasal cavity is so sensitive that it can differentiate hundreds of distinct odors, making it 10,000 times more sensitive than taste. About 350–400 types of odor receptors in the nasal cavity help us sense food smell.

Temperature. Hot and cold affect whether a food tastes good. The same amount of sugar tastes sweeter at higher temperatures, while the opposite is true for salt—the same amount of salt tastes saltier at lower temperatures. Combining cold and hot temperatures or hot and spicy foods in the same dish enhances flavor.

Appearance. Meals and foods that are brightly colored are generally more appealing than dark or bland-colored foods, except for green foods, which may be rejected if associated with bitter vegetables. Also, some foods look tasty, while others look unappetizing.

Updated July 1, 2021

References

Breslin, P.A.S. 2013. An evolutionary perspective on food review and human taste. Current Biology, 23 (9), R409–18.

Feeney, E., et al. 2011. Genetic variation in taste perception: Does it have a role in healthy eating? Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 70 (1), 135–43.

Natalie Digate Muth, MD, MPH, RD

"Natalie Digate Muth, MD, MPH, RDN, FAAP, is a board-certified pediatrician and obesity medicine physician, registered dietitian and health coach. She practices general pediatrics with a focus on healthy family routines, nutrition, physical activity and behavior change in North County, San Diego. She also serves as the senior advisor for healthcare solutions at the American Council on Exercise. Natalie is the author of five books and is committed to helping every child and family thrive. She is a strong advocate for systems and communities that support prevention and wellness across the lifespan, beginning at 9 months of age."