The 4 Most Common Running Injuries and How to Address Them

Every personal trainer has clients who enjoy running. They can become notably upset when an injury prevents them from engaging in their beloved pastime. Running is a popular and accessible exercise that millions of people like doing; in the United States alone, there are almost 40 million regular participants (Messier et al. 2008). While running is an effective way to maintain health, lose weight, enhance performance and ward off disease, it's also associated with a high risk of injury, with almost half of all runners reporting an injury at least once a year (Messier et al. 2008).

Most running injuries affect the lower body, with up to 79% occurring in the lower extremities (Van Gent et al. 2007). The four lower-body injuries runners experience most often are plantar fasciitis, Achilles tendinitis, patellofemoral syndrome ("runner's knee") and iliotibial (IT) band syndrome (Hespanhol et al. 2011). These common injuries result from musculoskeletal and movement imbalances compounded by overuse—especially in runners who clock more than 20 miles per week (Messier et al. 2008).

In your role as a fitness professional, you will work with many clients who develop—or want to avoid—running injuries. Clients will often share with you concerns about an injury diagnosis they've received from a licensed medical professional. While it is not within your scope of practice to confirm or diagnose medical conditions, it is important to have a basic understanding of common running injuries, because it helps you communicate effectively with clients about their diagnoses. Master your role in addressing the musculoskeletal and movement imbalances underlying clients' problems by educating yourself about the most common injuries and how to use corrective-exercise techniques to address them.

Basic Biomechanics

The musculoskeletal system experiences a lot of stress and strain during running. Gravity exerts tremendous downward pressure on both the skeleton and the soft-tissue structures. Once the foot strikes the ground, impact (ground reaction forces) creates an equal amount of force that transfers back up through the system. Fortunately, the human body has many important structures and clever techniques for dissipating these forces (Ayyappa 1997).

When we run (or perform any full-body, dynamic movement), the body moves in all three planes of motion (i.e., side to side, in rotation, and forward and backward). Side-to-side movements enable us to take alternating steps from left to right, helping to propel us forward or backward. As we move our legs forward or back, we also swing our arms forward and back, which creates rotation in the torso, thus enabling the spine, hips and legs to move. This movement combination helps us temporarily overcome gravity in order to complete an activity. However, these movements also help us absorb shock—those ground reaction forces—by allowing the body to move in the direction of impact, which is opposite to the direction of the pull of gravity. An effective way to comprehend how the musculoskeletal system manages these equal but opposing forces is to bring to mind the famous crash-test dummy commercials in which the dummy recoils as the vehicle hits the wall.

In addition to movement, the body has other strategies for dealing with gravity and ground reaction forces. Soft-tissue structures (especially our muscles) dissipate energy as impact travels back up the body (Ayyappa 1997). When a person is running, for example, certain muscles contract to swing the leg forward. As the foot strikes the ground and the body has to deal with impact, the muscles of the foot, ankle and leg lengthen under tension—like a trampoline skin stretching under tension when you jump on it. The muscle tension helps the body absorb shock and creates energy for subsequent movements (in the same way the stretched skin of the trampoline helps you jump higher).

If muscles are not healthy, flexible and strong, they are less effective at transferring weight and absorbing shock—much like an old trampoline skin. As a result, other soft tissues in the body—such as fascia, tendons and ligaments—must work harder. Over time, these structures become overworked, stressed and strained, leading to injury, pain and further dysfunction. That is why common overuse injuries manifest in connective tissue (see the sidebar "The Four Most Common Running Injuries" for more).

Similarly, if muscles aren't working correctly the joints can become inflamed or lack range of motion. Movements then become restricted and the body becomes less effective at dissipating gravity, absorbing shock and creating energy for movement. This often manifests as inflammation and joint problems. If you want to help clients gain or retain the ability to run without pain, and you want to help them minimize their potential for injury, then it is crucial to understand how muscular limitations—and associated skeletal and movement imbalances—cause running injuries (Price & Bratcher 2010).

Which Muscles/Movements Are Most Important For Running?

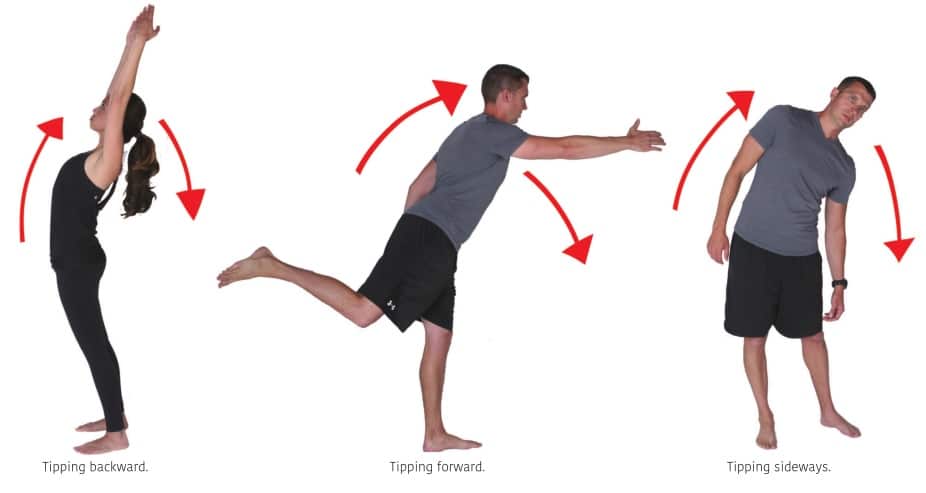

Some movements that occur while running require more eff ort than others, which can increase muscle fatigue and cause subsequent connective tissue and joint damage. Leaning forward or backward is an easy movement to initiate, because gravity helps to pull you in either direction. Resisting this downward pull is more difficult, though. It requires a lot of effort from muscles that help to keep you erect: the erectors and hamstrings, which work posteriorly to slow you down as you lean forward; and the abdominals and hip flexors, which lengthen to slow you down as you lean backward. Similarly, tipping to one side is easy because once you initiate the sideways bend, gravity pulls you in that direction. However, sideways movement is also difficult to resist, as it requires a lot of strength from the obliques, quadratus lumborum, erectors and abductors to prevent you from falling over (Myers 2008).

Rotating the body on a vertical axis is different. Rotation requires more muscular strength to start, because gravity doesn't help initiate the movement. Once rotational movements begin, however, they're easier to maintain because they're driven by momentum and unfettered by gravity. In addition, many of the largest muscles in the body are designed to help control rotation, because they wrap around the body (e.g., latissimus dorsi, obliques, glutes, etc.). Thus, when the body rotates well, movement stress is minimized because these large, powerful muscles transfer weight and absorb shock. Moreover, these big muscles also store energy by lengthening under tension (like a stretched bungee cord) when the body rotates. When released, this tension helps counter the rotation, making it easier to run faster and more efficiently. For example, when you turn your torso to the left , your obliques lengthen/stretch under tension to slow down stress to your spine and torso. Release of this tension then helps you turn to the right (Price 2010).

Effective rotational movements, therefore, are the key to avoiding running injuries because these are the movements least affected by gravity and impact. To understand the importance of the body being able to rotate when running, think of a spinning top. Once the top is turning, it can spin for a long time, as it is being driven by momentum. However, if the top starts wobbling and teeter-tottering from side to side (and forward and backward), it slows down quickly as gravity pulls it over and it comes to an abrupt stop. Therefore, the easiest way to dissipate stress throughout the body when running—and to minimize the risk for injury—is to ensure that the major joint structures in the body can rotate and the muscles that facilitate rotation are strong, healthy and flexible (see the sidebar "Rotational Movement Assessments" for more).

The Finish Line

Although running with correct mechanics improves health and function, musculoskeletal and movement imbalances—if left unchecked—can make the activity a painful and frustrating experience. When you learn how to properly assess and correct clients' limitations, you decrease the potential for pain and you increase your reputation as the "go-to" fitness professional for addressing sports-related injuries.