Posture Correction for Static Damage

Think of the three “S”s—Sitting, Standing and Sleeping—when making postural adjustments.

Updated July 7, 2021

The word posture tends to evoke the image of a schoolgirl standing perfectly erect with a book on her head. More accurately, static posture refers to the way in which a person holds his or her body or assumes certain positions, such as sitting, standing or sleeping. The cumulative effect of the time spent in certain positions can lead to prolonged static-posture damage to both the musculoskeletal and myofascial systems of the body. Therefore, this effect must be addressed in conjunction with an exercise program to ensure that clients remain pain free and fully functional.

Posture and Sitting

The human body is designed to be upright and weight bearing on two feet, with the hips extended under the spine to support the torso and head. This bipedal position has enabled us to move around for thousands of years and accomplish the various tasks needed for survival. Unfortunately for our body, the Industrial Revolution paved the way for standardization and automation of many tasks. The technological advancements of computers over the past 50 years have taken things further and launched us into a brand-new era that diminishes the need for coordinated multiplanar movements in our daily lives. Instead of standing erect and walking upright, people are spending more and more of their time in seated positions. Extended seated postures have a detrimental effect on various soft-tissue structures and muscles throughout the body.

From a musculoskeletal perspective, prolonged periods of sitting over many years are not good for the body. When a person is seated, the lumbopelvic hip girdle, thoracic spine, shoulder girdle, legs and feet are no longer required to engage in some of their major functions. The hips and spine no longer have to extend, and the feet no longer have to accept the weight of the body.

Instead, the hips remain in flexion, and the chair supports the body’s weight. As a result, the glutes no longer have to work to extend the hips, which soon become dysfunctional (Golding & Golding 2003). Furthermore, the hip flexors and abdominals become chronically shortened and compressed in this bent-hip and rounded-spine position that results from sitting (Wilson 2002). Therefore, when a person is required to stand after a prolonged period of sitting, other muscles that are not designed for the job initiate the movement. This can lead to overuse of certain tissues, potentially causing back, hip, knee and foot pain.

Several upper-body problems can also develop as a result of chronic sitting. When a person is seated in front of a computer or in the driver’s seat of a car, the arms and hands are placed in front of the torso. This forward position of the arms and hands causes the shoulders to round forward and the spine to flex, creating numerous restrictions in the fasciae and muscles of the torso (Freivalds 2004). Additionally, this forward position of the arms and shoulders means that the neck and head must adjust (by tilting the head upward) to keep the eyes aligned with the horizon or object (e.g., the computer screen, television or road). This adjustment of the head position creates an excessive arching of the neck, which over time can lead to imbalances, pain and dysfunction in these areas.

See also: Corrective Exercise for Foot, Ankle, Knee and Back Pain

Standing Posture

A prolonged sitting posture makes it very difficult upon standing to erect the spine and extend the hips. Additionally, since the feet do not have to bear the weight of the body or deal with ground reaction forces when seated, their system of arches becomes weak. Thus, when we must stand, our feet are less able to accept our body weight, and the arches collapse (i.e., overpronation occurs).

When the feet are no longer capable of handling the body’s weight, a person may develop the habit of shifting from side to side in an effort to redistribute the weight and alleviate the discomfort. This continual shifting can cause problematic changes in all the structures of the body.

Footwear is another important factor that can contribute to the development of painful and dysfunctional standing positions. High-heeled shoes tip the body’s center of gravity forward. Hence, when you place your feet into shoes that are not parallel to the floor, the entire body has to shift in order to avoid toppling forward. The knees, for example, may have to remain slightly bent, which can eventually lead to knee pain. The raised-heel position will also raise the back of the pelvis, which can result in excessive arching of the lower back. Consequently, people who stand or walk around in high-heeled shoes for extended periods of time will often experience lower-back pain.

See also: Corrective Exercise Success Story

Sleeping

Chronic muscular imbalances and restrictions created by prolonged seated and standing postures can make it very uncomfortable when it comes to sleeping, particularly for those who lie on their backs. People with an excessive arch in the lower back often have very tight hip flexors (McGill 2002). Therefore, sleeping on the back with legs straight can pull the lumbar spine forward toward the legs. This will make the arch in the lower back even greater, which may cause pain. For this reason, people with such imbalances will likely prefer sleeping on their sides.

However, sleeping this way for prolonged periods can create problems as well. When a person is sleeping on the side, the arms usually drop across the front of the torso as the upper back and shoulders round. Over time, this sleeping position can lead to myofascial restrictions across the chest, front of the shoulders, and abdominals. Upon rising, this type of sleeper may experience pain in the shoulders, neck and/or upper back.

There are also many people who like to sleep on the stomach. Sleeping on the stomach can arch the lower back excessively and twist the neck. If you have clients who prefer to sleep face down, it is extremely important to encourage them to change this habit.

Many soft-tissue changes can occur from standing, sitting and sleeping in chronically misaligned postures. The impact of these prolonged static positions can be far-reaching and will have a direct effect on the success of your clients’ exercise programs. As such, it is important to incorporate corrective exercises and suggest non-exercise-related solutions to minimize the corporeal stress.

The following exercises can be integrated into personal training sessions to alleviate some of the musculoskeletal imbalances and pain caused by extended static postures.

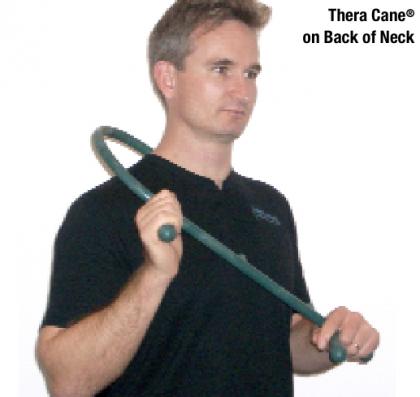

This trigger-point massage technique is used to rejuvenate and regenerate the muscles and fasciae on the back of the neck that can get chronically shortened from arching the neck back and up to look at a computer screen.

Coach clients to apply steady pressure to any sore spots they feel on the back of the neck from the top of the shoulders all the way up to the base of the skull. Perform for 3–5 minutes daily.

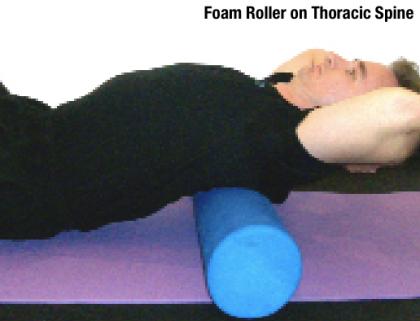

This myofascial release technique is used to reduce muscle tension and fascial restrictions in the soft-tissue structures of the thoracic spine. The roller also acts as a fulcrum to create extension in the thoracic spine.

Coach clients to lie back over the foam roller with a supported head. Teach them to posteriorly tilt (i.e., tuck under) the pelvis to reduce the tendency to arch the lower back. Instruct them to roll from the midback up to the shoulders while remembering to inhale and exhale. Perform for 2–3 minutes daily.

This integrated stretch helps condition the calves, hip flexors, abdominals, thoracic spine and shoulder girdle to extend the hips and hold the torso erect.

Instruct clients to step the right leg through a doorframe and keep the left leg back as they reach up with the left arm to the doorjamb. They should tilt the pelvis posteriorly and keep the left heel on the ground. Clients should feel this stretch in the front of the left hip, abdominals and back of the left calf. Switch to the other arm and leg. Repeat 1–2 times on each side.

This integrated stretching and strengthening exercise stretches the hip flexors and abdominals while strengthening the gluteal muscles and thoracic extensors to extend the hips and hold the spine erect.

Coach clients to step back with the right leg as they swing the right arm up in line with the ear. As they step back, instruct them to engage the right gluteal muscles to push their hips forward. Make sure that they extend the thoracic spine and don’t overarch the lower back. Switch to the other arm and leg. Perform 3–5 repetitions on each side (photos show start and end positions).

There are many non-exercise-related adjustments that can alleviate some of the problems caused by prolonged seated, standing and sleeping postures.

Sitting

- Encourage clients to get out of their chairs several times a day to promote hip/leg and spine extension.

- Suggest they convert their workspace to a standing desk or walk when possible instead of driving.

- Coach clients to change chairs and positions often or alternate sitting on a stability ball with sitting on an office chair.

- Remind clients to check and/or adjust the positioning and alignment of their computer monitors, telephones, steering wheels, chairs, televisions, computer accessories and keyboards.

Standing

- Make clients aware of habits like shifting weight from side to side when standing.

- Educate them about good footwear choices, and encourage them to gradually incorporate footwear changes into their daily lives.

- Make clients aware of their upper-body postures when standing. Crossing the arms, talking on a cell phone, carrying a heavy bag on one shoulder or putting hands in pockets can all create problematic shifts or fascial restrictions in the body.

Sleeping

- Encourage clients to sleep in a supine position on a bed that is firm enough, so that neither the lower back nor thoracic spine sinks into the mattress. If a client feels uncomfortable in this position, recommend placing a wedge or pillow(s) under the knees to posteriorly tilt the pelvis (thereby helping to keep the lumbar spine and pelvis nearer to a neutral position). Coach clients to start off in this position for just a few minutes a night and gradually increase the amount of time they spend this way. As the structures of the lumbar spine begin to adjust, pillow height (with pillow under the knees) can be reduced.

- Coach clients to choose a pillow thickness that puts their eyes in a position that is perpendicular to the ceiling. This will support the back of the neck and head. Ensure that the pillow thickness is not so great that it pushes the head too far forward.

- Encourage side-sleeping clients to place a pillow between the knees to keep the top leg in line with the hip socket. The pillow they use for the head should be thick enough to keep the head in line with the spine.

References

Abelson, B., & Abelson, K.T. 2003. Release Your Pain. Calgary, AB: Rowan Tree Books.

Barnes, J.F. Myofascial release. 1999. In W.I. Hammer (Ed.), Functional Soft Tissue Examination and Treatment by Manual Methods (2nd ed). Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen.

Calvert, R.N. 2002. The History of Massage: An Illustrated Survey From Around the World. Rochester, VT: Healing Arts.

Freivalds, A. 2004. Biomechanics of the Upper Limbs: Mechanics, Modeling and Musculoskeletal Injuries. Boca Raton, FL: CRC.

Golding, L.A., & Golding, S.M. 2003. Fitness Professional’s Guide to Musculoskeletal Anatomy and Human Movement. Monterey, CA: Healthy Learning.

Gray, H. 1995. Gray’s Anatomy. New York: Barnes & Noble Books.

Kendall, F.P., et al. 2005. Muscles: Testing and Function, with Posture and Pain (5th ed.). Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

McGill, S. 2002. Low Back Disorders: Evidence-Based Prevention and Rehabilitation. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Price, J. 2009. A Step-by-Step Guide to the Fundamentals of Corrective Exercise. Educational DVD Series. Space Café Media.

Price, J. 2009. A Step-by-Step Guide to the Fundamentals of Structural Assessment. Educational DVD Series. Space Café Media.

Price, J. 2009. A Step-by-Step Guide to Understanding Muscles and Movement. Educational DVD Series. Space Café Media.

Rolf, I. P. 1989. Rolfing: Reestablishing the Natural Alignment & Structural Integration of the Human Body for Vitality and Well-Being (revised edition). Rochester, VT: Healing Arts.

Whiting, W.C., & Zernicke, R.F. 1998. Biomechanics of Musculoskeletal Injury. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Wilson, A. 2002. Effective Management of Musculoskeletal Injury: A Clinical Ergonomics Approach to Prevention, Treatment and Rehabilitation. London: Churchill Livingstone.

Justin Price, MA

Justin Price, MA, is creator of the BioMechanics Method® Corrective Exercise Specialist (TBMM-CES) program, the fitness industry’s highest-rated CES credential, with trained professionals in 80 countries. He is also the author of several books, including The BioMechanics Method for Corrective Exercise academic textbook, and he was awarded the 2006 IDEA Personal Trainer of the Year. He has served as a subject matter expert for numerous brands and media organizations including ACE, TRX® and BOSU®; the BBC, Discovery Health and MSNBC; Arthritis Today, Men’s Health, Newsweek, Time, WebMD and Tennis; and Los Angeles Times, The New York Times and Wall Street Journal. Learn more about The BioMechanics Method®