Spine-Chilling Science: How to Keep Your Back Strong and Supported

Introduction: Why Your Spine Matters

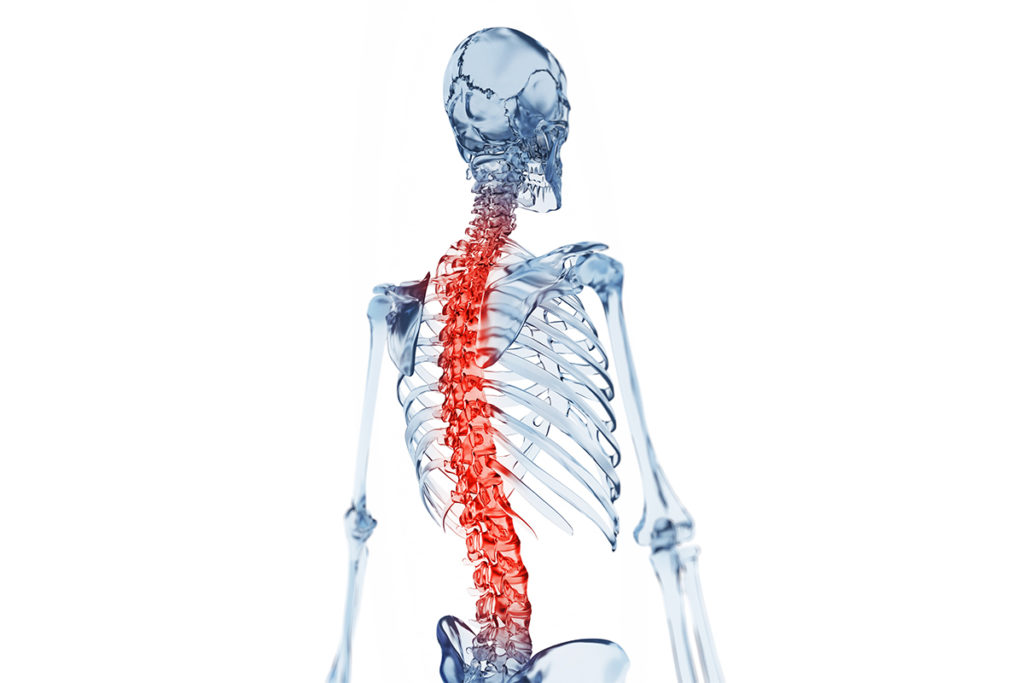

The human spine is often described as the backbone of the body—both literally and figuratively. It supports our posture, enables movement, and protects one of the most important structures in the nervous system: the spinal cord. Despite its strength, the spine is also a source of discomfort for many. Back pain is one of the most common health issues worldwide, affecting people of all ages and lifestyles.

Understanding how the spine works is the first step toward protecting it. With basic knowledge of spinal anatomy and function, everyday actions like sitting at a desk, lifting groceries, or going for a walk can be done in ways that promote long-term spinal health.

For most people, spinal health is not top of mind until something goes wrong. A sudden twinge of pain while bending, a stiff neck after long hours at the computer, or chronic discomfort from years of poor posture can quickly become daily frustrations. Taking time to learn about the spine before problems arise can prevent these issues altogether. Preventive care is always easier and more effective than trying to reverse years of accumulated strain.

Finally, spinal health is not just about avoiding pain. A strong, supported spine enhances quality of life. It allows us to play with our children, travel, participate in hobbies, and stay active as we age. Protecting your spine is an investment in independence and mobility, both now and decades into the future.

Anatomy of the Spine: The Body’s Central Column

The spine is made up of 33 vertebrae, arranged into five regions:

- Cervical spine (neck): 7 vertebrae supporting the head and allowing wide ranges of motion like nodding and rotation.

- Thoracic spine (mid-back): 12 vertebrae connected to the rib cage, providing stability and protection for vital organs.

- Lumbar spine (lower back): 5 large vertebrae designed to bear the body’s weight and enable bending and lifting.

- Sacrum: 5 fused vertebrae that connect the spine to the pelvis.

- Coccyx (tailbone): 4 fused vertebrae at the very base of the spine.

This segmented design balances stability and flexibility. Intervertebral discs, which are cartilage cushions between each vertebra, absorb shock during movement. Together, these structures allow us to bend, twist, and move with both strength and grace (Standring, 2021).

Each spinal region has a natural curve that contributes to balance and shock absorption. The cervical and lumbar regions curve inward (lordosis), while the thoracic and sacral regions curve outward (kyphosis). These curves distribute forces evenly across the spine. When posture or muscular imbalances distort these curves, stress builds up in certain areas, leading to discomfort or long-term degeneration.

The complexity of the spine is part of what makes it both resilient and vulnerable. Its ability to move in multiple planes—flexion, extension, rotation, and lateral bending—makes human movement possible, but repeated poor mechanics or high loads can stress its structures. For everyday readers, simply understanding that the spine has natural curves and works as a system of interconnected parts can be enough to improve daily awareness.

The Spine as Protector: Safeguarding the Spinal Cord

Beyond support and movement, the spine protects the spinal cord, a delicate bundle of nerves that transmits information between the brain and body. This communication pathway controls movement, sensation, and reflexes. Damage to the spinal cord can have life-changing consequences, which highlights why protecting spinal health is so important.

Everyday actions like avoiding sudden twisting with heavy loads, practicing safe lifting mechanics, and wearing seatbelts can make a difference in preserving both spinal integrity and neurological health.

The spinal cord itself is remarkably efficient but also highly sensitive. Even minor compression from a herniated disc can cause tingling, weakness, or pain that radiates into the arms or legs. This is why it’s so important to take small episodes of pain seriously rather than ignoring them. Early intervention—whether through rest, physical therapy, or lifestyle adjustments—can prevent a small issue from becoming a chronic condition.

The protective role of the spine also emphasizes the importance of minimizing trauma. Sports safety equipment, proper footwear, and fall-prevention strategies for older adults all reduce risk. Protecting the spinal cord is not only about athletic performance or posture—it’s about safeguarding the central highway of communication that allows the entire body to function properly.

Muscles That Support the Spine

The spine does not work alone. Muscles provide crucial reinforcement, particularly:

- Core muscles: The abdominals and deep stabilizers brace the spine.

- Gluteal muscles: Strong glutes stabilize the pelvis, which influences spinal alignment.

- Back muscles: The erector spinae and multifidus help maintain posture and control spinal movement.

When these muscles are weak or imbalanced, the spine is more vulnerable to pain and injury. That is why strengthening the core, hips, and back is a cornerstone of spinal health.

For example, when the core muscles are underactive, the lumbar spine often bears more load than it should. Similarly, weak glutes can cause the pelvis to tilt forward, placing strain on the lower back. Strength training exercises like planks, bridges, bird dogs, and squats all help reinforce these key stabilizers.

In addition to strength, endurance matters. Posture requires low-level muscle activation for extended periods, not just bursts of strength. Building muscular endurance through activities like walking, Pilates, or yoga helps maintain spinal support throughout daily life. A strong, well-conditioned support system gives the spine the backup it needs to handle both everyday tasks and physical challenges.

Common Spine-Related Issues in Daily Life

Poor posture, sedentary habits, and repetitive motions all contribute to spinal stress. Slouching at a desk, carrying heavy bags on one shoulder, or looking down at a phone for hours can lead to discomfort over time. Lower back pain is particularly widespread, and while it often resolves with conservative measures, chronic back issues can significantly limit quality of life.

Lifestyle choices also matter. Smoking, obesity, and lack of exercise increase the risk of degenerative spinal conditions. Conversely, staying active, maintaining a healthy weight, and practicing good ergonomics can help protect spinal health.

Technology has introduced new challenges, such as “text neck,” caused by constantly looking down at phones or laptops. This posture puts added pressure on the cervical spine. Over time, the imbalance can lead to headaches, shoulder pain, and even nerve irritation. Awareness and correction—such as raising devices to eye level and taking posture breaks—can make a big difference.

Spinal issues also differ across life stages. Children and teens may develop scoliosis or posture-related imbalances from heavy backpacks. Adults often struggle with lower back pain related to sedentary jobs. Older adults may face osteoporosis or spinal stenosis. Recognizing these patterns can help individuals address problems proactively at each stage of life.

Practical Tips for Everyday Spinal Health

- Practice good posture: Keep shoulders back, ears aligned with shoulders, and weight evenly distributed.

- Set up ergonomics: Use chairs that support the natural curve of the spine and adjust screens to eye level.

- Move often: Avoid sitting for more than 30–60 minutes at a time; stand up and stretch regularly.

- Lift smart: Bend at the hips and knees, keep objects close to the body, and avoid twisting while lifting.

- Strengthen consistently: Core training, walking, and resistance exercise all build spinal support.

These simple strategies may seem basic, but they are highly effective. Consistency is the key—making posture checks, short breaks, and proper lifting habits part of your daily routine.

Another practical tool is stretching. Gentle daily stretches for the hamstrings, hip flexors, and thoracic spine can relieve tension that pulls on the spine. Pairing stretching with core strengthening ensures that flexibility and stability balance each other. Small lifestyle adjustments compound over time, creating big changes in spinal health.

Even simple daily choices like wearing supportive shoes or sleeping on a medium-firm mattress can have a significant impact. Spinal health is not just about exercise—it is about creating an environment that allows the spine to function at its best.

The Role of Exercise in Spinal Health

Exercise is one of the most effective tools for maintaining a healthy spine. Walking promotes circulation and gentle spinal motion. Strength training builds the muscles that stabilize and protect the spine. Flexibility and mobility work, such as yoga or dynamic stretching, reduce stiffness and improve posture.

Even short daily routines can create long-term benefits. A few minutes of core strengthening, glute activation, or back mobility drills can reduce the risk of injury and improve daily comfort.

Importantly, exercise should be progressive and balanced. Focusing only on one area—such as crunches for the abdominals—without considering the entire kinetic chain can create imbalances. A well-rounded program includes movements for strength, mobility, endurance, and stability.

For individuals who are new to exercise or dealing with pain, low-impact options such as swimming or Pilates can provide spinal benefits without excessive strain. Over time, building a varied exercise routine helps maintain spinal resilience, supporting both daily function and long-term health.

Invest in Your Spine

Your spine is more than a structure—it is your body’s foundation. By learning about spinal anatomy, practicing healthy posture, strengthening supportive muscles, and prioritizing smart daily habits, you can protect your back for years to come.

Taking care of your spine is an investment in mobility, independence, and quality of life.

Think of spinal care as a lifelong project. Small steps taken today—like adjusting posture, staying active, and strengthening your core—pay off in the form of reduced pain, better movement, and sustained energy. The spine supports every action we take; it deserves equal support in return.

References

Cheng, M., Tian, Y., Ye, Q., Li, J., Xie, L., & Ding, F. (2025). Evaluating the effectiveness of six exercise interventions for low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 26, Article 433. BioMed Central

González-Gálvez, N., et al. (2024). Effects of stretching or strengthening exercise on spinal and lumbopelvic posture: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Sports Medicine – Open. SpringerOpen

“Benefits and harms of exercise therapy and physical activity for low back pain.” (2025). ScienceDirect. (Umbrella review of 70 systematic reviews) ScienceDirect

“Preventing and managing degenerative lumbar spine disorders.” (2025). BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. (AI-based decision support systems in LBP care) BioMed Central

“Therapeutic exercise following lumbar spine surgery: a narrative review.” (2025). NASS Open Access. NASS Open Access

“Exercise therapy can improve trunk performance and sitting balance in spinal cord injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis.” (2025). Neurological Sciences. SpringerLink

“Spinal cord injuries: pathophysiology, molecular mechanisms, and omics approaches.” (2025). International Journal of Molecular Sciences. MDPI

“Traumatic spinal cord injury: a review of the current state of art.” (2025). NASS Open Access. NASS Open Access

“Frontiers | Clinical efficacy of exercise therapy for lumbar disc herniation.” (2025). Frontiers in Medicine. Frontiers

“Are we doing enough? Lifestyle interventions for enhancing spine health.” (2024). ScienceDirect / review article on exercise, strength, flexibility, and risk reduction of back injuries. ScienceDirect