Helping Clients Enjoy the Taste and Culture of Food

Coaching clients to embrace the tastes and textures of new food and to practice mindful eating can help them reach their nutrition goals with less focus on fad diets and calorie counting.

It’s time for Americans to shift their focus from calories, macronutrients and micronutrients to taste, culture and mindfulness. After all, our preoccupation with dieting and health fads has us restricting foods, chasing unsustainable weight loss goals and feeling bad about our nutrition choices—but all we have to show for it is rising rates of overweight, obesity, diabetes and heart disease.

Fitness pros can help to turn things around by encouraging clients to reorient their mindsets about food and eating. You can guide clients on savoring and enjoying food, learning to like new tastes and textures, and incorporating cultural practices and mindfulness into their eating routines. These approaches will do more than dieting and weight loss to help your clients improve their overall nutrition, health and well-being. The key is understanding how flavor works (see “Where Flavor Comes From,” below) and why we’re so intent on eating foods that are not good for us.

Born With a Sweet Tooth

Studies find that perceived taste is the strongest predictor of which foods a person eats (Feeney et al. 2011). Moreover, humans are born with an innate preference for sweet and salty foods.

Statistics bear this out: The average American consumes 73 grams of added sugars per day—that’s 292 calories, much more than the recommended limit of less than 10% of total daily calories (Bowman et al. 2017). We also take in 3,400 milligrams of sodium per day, well above the recommended maximum of 2,300 mg (CDC 2017). And while we consume too many calories and too much sugar and salt, fewer than 10% of us eat the recommended 2–3 cups of vegetables per day.

Simply eating the recommended amounts of vegetables can be one of the best ways to improve nutrition and health (Lee-Kwan et al. 2017). The challenge is that people may have an innate dislike of the bitter tastes they associate with certain vegetables.

Innate taste preferences are rooted in evolution. Our hunter-gatherer ancestors needed to distinguish safe and healthful foods from potential toxins. Sweet foods like berries were generally safe to eat, while bitter plants were more likely to be toxic. Our ancestors also chose foods that satiated them for a long time, as the next meal was never guaranteed. Thus, we have evolved to prefer sweet tastes, avoid bitter ones, and efficiently store fat and calories. While this adaptation was essential in the age of foraging, it’s a liability in our era of easy access to an abundance of food that requires little physical activity to acquire. Meanwhile, advances in science and technology allow manufacturers to produce an almost infinite variety of foods perfectly designed to delight the taste buds, activate reward centers in the brain and induce overconsumption.

Components of Taste

“SUPERTASTERS” VS. “NONTASTERS”

About 20% of people carry a gene that makes them “supertasters.” They have many more taste buds than average on the fungiform papillae, making this group extra-sensitive to bitter tastes, which they often find disgusting.

About 30% of people are nontasters, with far fewer taste buds than average on the fungiform papillae; this group hardly notices bitter tastes (Feeney et al. 2011).

Where Flavor Comes From

Flavor represents the tactile experience of eating. Flavor sensations emanate from the tongue, palate, teeth, nose, eyes and fingers. “The Jelly Bean Experiment,” below, gives a sense of how perception changes our concept of flavor (Owen 2015).

The Tools of Taste

The tongue, mouth and nasal cavity speed messages to the brain to help identify tastes, textures and odors. A brain region called the gustatory cortex contains thousands of neurons that respond to individual tastes.

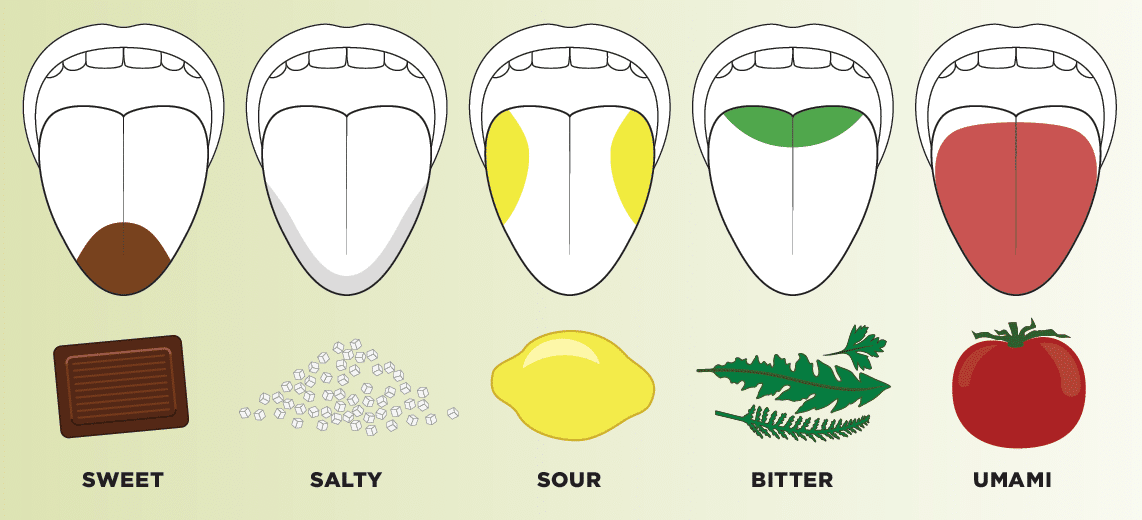

The principal tasting mechanism is the taste bud, a bundle of nerves that sense five kinds of flavors: sweet, sour, bitter, salty and umami (savory). Generally, simple carbohydrates taste sweet, the amino acids glutamate and aspartate taste savory, acids taste sour, and many toxic compounds plus some vegetables taste bitter (Breslin 2013).

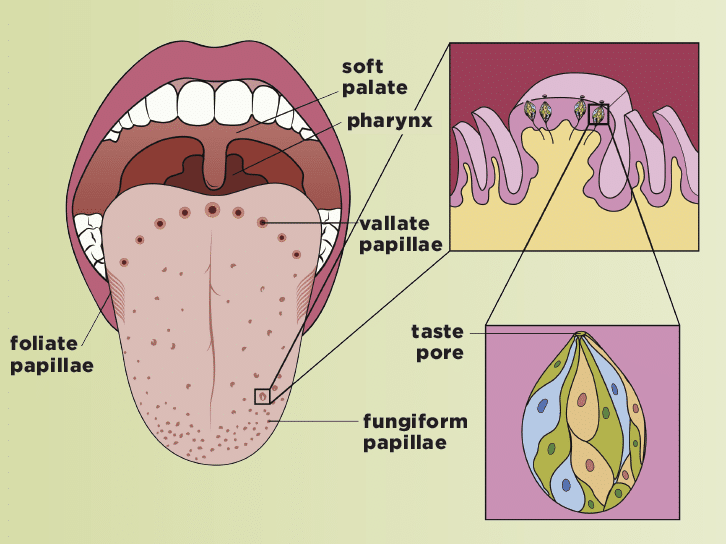

Taste buds detect flavor in three locations: the tongue’s papillae (bumps), the soft palate and the pharynx (see “Components of Taste,” above). Papillae with tasting function come in three types:

- vallate, which form an arc on the rear third of the tongue

- foliate, small slit-like bumps on the sides of the tongue

- fungiform, small bumps on the front two-thirds of the tongue

The vallate and foliate papillae contain hundreds of taste buds, while each fungiform papilla has 10–15 taste buds.

More Factors That Influence Flavor

Texture. Filiform papillae on the front two-thirds of the tongue detect the texture of foods but have no tasting function (Breslin 2013). Most people prefer crispy, crunchy, tender, juicy and firm textures and dislike tough, soggy, crumbly, lumpy, watery and slimy textures.

Aroma. The smell center in the rear of the nasal cavity is so sensitive that it can differentiate hundreds of distinct odors, making it 10,000 times more sensitive than taste. About 350–400 types of odor receptors in the nasal cavity help us sense food smell.

Temperature. Hot and cold affect whether a food tastes good. The same amount of sugar tastes sweeter at higher temperatures, while the opposite is true for salt—the same amount of salt tastes saltier at lower temperatures. Combining cold and hot temperatures or hot and spicy foods in the same dish enhances flavor.

Appearance. Meals and foods that are brightly colored are generally more appealing than dark or bland-colored foods, except for green foods, which may be rejected if associated with bitter vegetables. Also, some foods look tasty, while others look unappetizing.

The Jelly Bean Experiment

This experiment can show clients how their perceptions can change their experience of flavor. It uses three jelly beans that taste the same—a fact kept secret from the participants.

Step 1. Ask clients to plug their nose and close their eyes. Remind them to keep their nose plugged until they have chewed and swallowed the first jelly bean. Ask them to guess the flavor of the jelly bean and write it down. Ask them to rate how much they like the jelly bean flavor on a scale of 1 (hate) to 10 (love).

Step 2. Ask clients to close their eyes but not their nose. Ask them to guess the flavor of the second jelly bean and write it down. Ask them to rate how much they like the jelly bean flavor on a scale of 1–10.

Step 3. Let clients use all of their senses. Have them guess the flavor of the third jelly bean and write it down. Ask them to rate how much they like the jelly bean flavor on a scale of 1–10.

Step 4. Compare the flavor “guess” for each step with the actual jelly bean flavor. Compare how much the clients liked or disliked the flavors they experienced in steps 1–3.

Key points: We get a lot of information about food through senses other than taste. Essentially, the jelly bean has a sweet taste, but it has no flavor if people plug their nose and cannot smell it. We should use all of our senses when eating. Likewise, when we’re preparing foods, we should consider the important role of each of the senses.

An Acquired Taste

While humans may be programmed to prefer sweet and salty foods and naturally dislike bitter and sour foods, our sense of taste can change over time. Babies exposed to a wide variety of healthy foods—first in utero, through amniotic fluid, next through maternal breast milk and then in the first several months of exposure to solid foods—generally come to like a broad diversity of foods. Toddlers have a natural tendency to reject new foods, a form of neophobia (aversion to novelty), but taste buds can learn to enjoy an unfamiliar food after many repeated exposures.

Consider how a young child in India or Thailand eagerly devours curry, while a typical U.S. toddler shuns even the mildest spices. Or think of how stinky tofu is popular across China—the stinkier, the tastier—but few people outside the region are willing to try the food (it tastes sweet, despite its stench).

Thus, food preferences often come down to cultural expectations, modeling and family influence during childhood and to re-engineering taste buds through repeated exposures. Best-selling food author Michael Pollan may have said it best: “Culture, when it comes to food, is of course a fancy word for your mom.”

People also come to prefer foods or tastes they associate with pleasant physical or social environments, while they tend to dislike foods with uncomfortable or negative associations. Familiar foods bring back memories and foster a sense of security. Food is a symbol of hospitality, an opportunity to bond with a friend or family member, and a perfect gift for a special occasion.

In many countries, specific foods and food rituals are tightly connected to national identity and pride. For example, French culture consists of three leisurely and pleasurable meals per day, eaten with family and friends, without snacks in between.

Culture and identity can also be associated with food rituals that are potentially detrimental to health. For example, U.S. Southern food culture includes routine consumption of foods like fried chicken with macaroni and cheese, collard greens with ham hocks, and fried okra. While these types of foods are considered traditional, eating them on a regular basis raises the risk of health problems like hypertension, heart disease, obesity and diabetes.

The solution isn’t to advise people to stop eating foods that are vital to their culture. Instead, we have to problem-solve in ways that honor and retain culture and tradition while also encouraging enjoyment of foods that support good health. This may mean cooking the same foods with less added fat, sugar and salt; savoring food while eating (and thus eating less); and reserving certain foods for special occasions.

If you learn more about clients’ cultural and individual taste preferences, food values and priorities, you will be more able to provide meaningful guidance that respects current preferences while helping the clients learn to savor new food experiences.

Six Ways to Savor Food Experiences

This six-step approach provides strategies for guiding clients to achieve better

health through more wholesome, mindful and adventurous eating.

1. ENCOURAGE CULTURAL FOOD EXPERIENCES

Foods and rituals around mealtimes provide insight into the values and history of a country or culture. Experiencing new ways of preparing foods, adding flavor, and facilitating social connection and pleasure at mealtimes can create positive memories and help train taste buds to appreciate new tastes and textures. You can play a role in encouraging clients to branch out.

You can also demonstrate ways to make food more flavorful without adding a lot of sugar and salt. Clients do not have to travel the world to have these experiences. A cooking class or a recipe that incorporates some of the following vegetable, herb and spice combinations can give a basic meal a cultural flair:

- Indian: garlic, onion, curry powder, cinnamon

- Asian: garlic, scallions, sesame, ginger, soy sauce

- Italian: garlic, basil, parsley, oregano

- Middle Eastern: garlic, onion, mint, cumin, saffron, lemon

- Mexican: cumin, onion, oregano, cilantro

See “Multicultural Marinades,” below, for quick and easy recipes.

2. PRACTICE SAVORING

People leading hectic lives often eat in a rush—mindlessly and without pleasure. Clients will enjoy food more—and eat less—when they slow down and savor the texture, taste, smell, feel and sound of the food. Help them appreciate the value of savoring by guiding them through “The Raisin Meditation,” below.

3. RAISE HUNGER AWARENESS

Help clients improve their ability to use hunger and satiety cues to guide food intake. Encourage them to ask themselves, before eating, “Am I hungry?” If the answer is no, then what prompted their desire to eat—boredom, stress, easy availability of the food, social cues?

If the answer is yes, then how hungry are they—extremely, very, a little bit? The aim is to eat when very hungry (stomach is beginning to growl) and stop when comfortably full, or—as the Japanese often say—Hara hachi bun me, which means, “Eat until you are 80% full.”

4. TRY, TRY AND TRY AGAIN

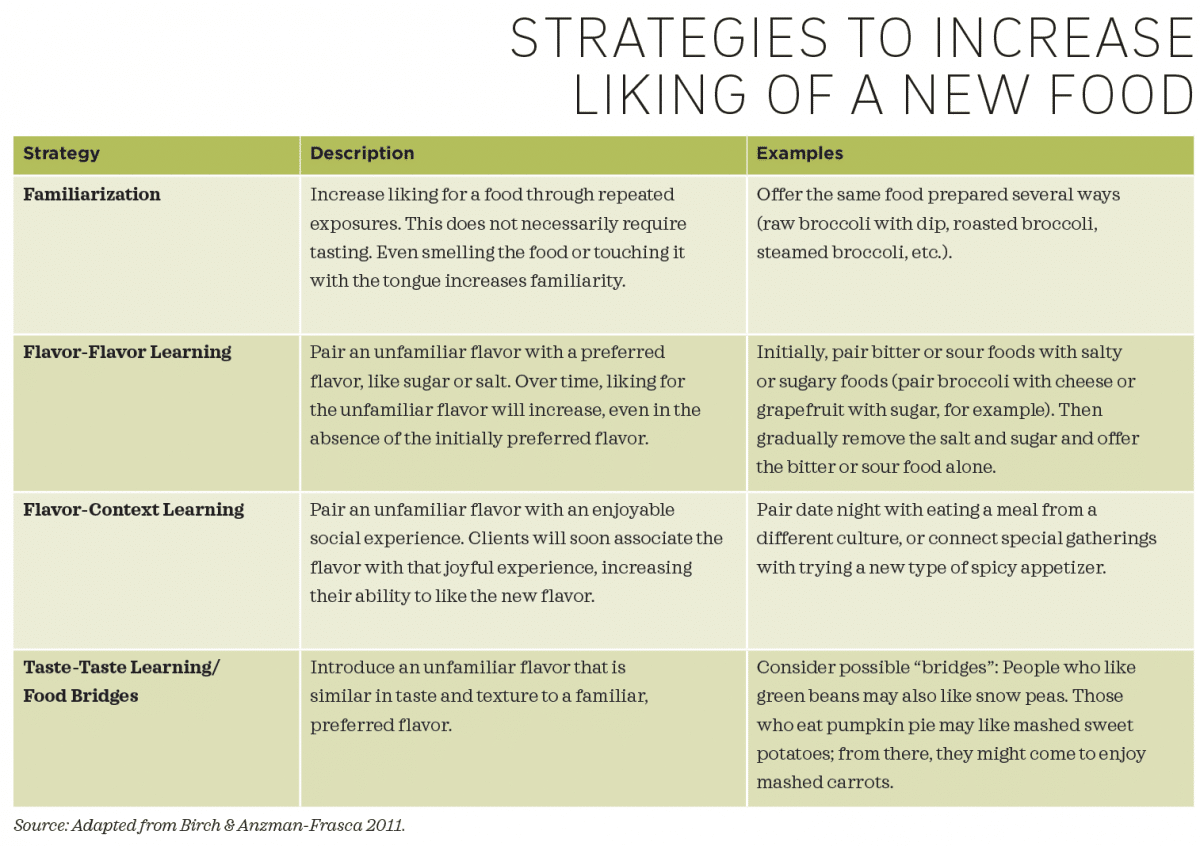

A large body of scientific research shows that people have to try a food a minimum of 8–10 times before they learn to like it, and even more often if they have more rigid preferences (Nekitsing et al. 2018). But with time and repeated exposures, foods once considered off-limits can become tolerable and even preferred. If clients hesitate to try a new, unfamiliar food, you don’t have to pressure them to eat it. Rather, try the research-based strategies described in “Strategies to Increase Liking of a New Food,” below.

5. MAKE UNHEALTHY FAMILIAR FOODS LESS FAMILIAR

Just as we can come to acquire a taste for bitter and sour foods, we can also reduce a craving or taste for sweet and salty foods by decreasing sugar and salt levels in the diet. At first, eating less of these foods triggers more cravings, but ignoring the cravings eventually causes them to recede, and super-sweet or very salty foods stop tasting so good.

6. PRACTICE MINDFUL EATING

Mindfulness includes several key principles, which are practiced together:

- nonjudging: being open-minded to the new and unfamiliar

- patience: slowing down and increasing awareness of the moment and the experience

- beginner’s mindset: approaching each experience as new

- trust: noticing, appreciating and accepting one’s own experience

- nonstriving: savoring the moment and ditching the dieting mindset

- acceptance: noticing and accepting one’s experience, whether positive or not

- letting go: allowing past expectations and attachments to fall away and starting anew

Source: Nelson 2017.

THE RAISIN MEDITATION

The raisin meditation can make eating a more mindful activity for clients by helping them to pay attention to each of their senses when eating a food. Here’s how it works:

- Place one raisin on a table.

- Imagine you have just been dropped on Earth, with no experiences. You’ve never seen nor tasted a raisin. Take a few deep breaths.

- Look at the raisin carefully. Notice its curves, wrinkles, shiny parts and dull parts.

- Pick up the raisin. Feel its weight.

- Roll the raisin between your fingers. Listen to its sound. Feel its stickiness.

- Smell the raisin.

- Notice how you feel about the raisin.

- Place the raisin in your mouth and hold it there. Do not bite down. What do you taste?

- Bite down on the raisin once. What do you notice?

- Slowly chew. What do you experience with each bite?

- Chew the raisin until it is liquid in your mouth before you swallow.

- Swallow the raisin.

- Close your eyes for a few breaths and consider what you just experienced.

Source: Adapted from Nelson 2017.

Transitioning from a focus on calories, nutrients, foods and dieting to a more mindful approach to eating makes clients more likely to improve their health. Moreover, they’ll come to appreciate a wider diversity of foods, tastes and cultures, which in turn yields more enjoyment and a higher quality of life.

Multicultural Marinades

Consider sharing these marinade ideas to help clients on their multicultural food journey.

Mexican Spice Marinade

1 t ground cumin

1 t dried onion

1 t ground oregano

1/2 C fresh cilantro

2 T olive oil

Asian Spice Marinade

1 t ground dried garlic (or 1 T fresh garlic)

2 bunches of scallions, chopped

1 T sesame seeds

1/2 inch of fresh ginger (or 1 t dried ginger)

1/2 C soy sauce

Middle Eastern Spice Marinade

1 t ground dried garlic (or 1 T fresh garlic)

1 t of dried onion

¼ C fresh mint

1 t ground cumin

2 T olive oil

¼ C plain yogurt

pinch of saffron

Italian Spice Marinade

1 t ground dried garlic (or 1 T fresh garlic)

1 t dried basil (or 1/4 C fresh basil, chopped)

1 t dried parsley (or 1/4 C fresh parsley, chopped)

1 t dried oregano

2 T olive oil

Recipe credit: Mary Saph Tanaka.

References

Birch, L.L., & Anzman-Frasca, S. 2011. Learning to prefer the familiar in obesogenic environments. Nestle Nutrition Workshop Series, Pediatric Program, 68, 187–99.

Bowman, S.A., et al. 2017. U.S. Department of Agriculture Food Survey Research Group. Added sugars intake of Americans: What we eat in America, NHANES 2013-2014. Food Surveys Research Group Dietary Data Brief, 18, Accessed Nov. 19, 2018: ars.usda.gov/ARSUserFiles/80400530/pdf/DBrief/18_Added_Sugars_Intake_of_Americans_2013-2014.pdf.

Breslin, P.A.S. 2013. An evolutionary perspective on food review and human taste. Current Biology, 23 (9), R409–18.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2017. Get the facts: Sodium and the Dietary Guidelines. Accessed Dec. 4, 2018: cdc.gov/salt/pdfs/sodium_dietary_guidelines.pdf.

Feeney, E., et al. 2011. Genetic variation in taste perception: Does it have a role in healthy eating? Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 70 (1), 135–43.

Lee-Kwan, S.H., et al. 2017. Disparities in state-specific adult fruit and vegetable consumption—United States, 2015. MMWR, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 66 (45), 1241–47.

Nekitsing, C., et al. 2018. Systematic review and meta-analysis of strategies to increase vegetable consumption in preschool children aged 2–5 years. Appetite, 127, 138–54.

Nelson, J.B. 2017. Mindful eating: The art of presence while you eat. Diabetes Spectrum, 30 (3), 171–74.

Owen, D. 2015. Beyond taste buds: The science of delicious. National Geographic. Accessed Dec. 4, 2018: nationalgeographic.com/magazine/2015/12/food-science-of-taste/.

Natalie Digate Muth, MD, MPH, RD

"Natalie Digate Muth, MD, MPH, RDN, FAAP, is a board-certified pediatrician and obesity medicine physician, registered dietitian and health coach. She practices general pediatrics with a focus on healthy family routines, nutrition, physical activity and behavior change in North County, San Diego. She also serves as the senior advisor for healthcare solutions at the American Council on Exercise. Natalie is the author of five books and is committed to helping every child and family thrive. She is a strong advocate for systems and communities that support prevention and wellness across the lifespan, beginning at 9 months of age."