Finding Contentment With Your Body and Your Yoga

The real purpose of practicing asanas is to learn about ourselves, not to achieve perfection.

For most of us, being content with what we have, who we are, what we do and what we look like is very challenging. We are flooded with images of people who are better-looking, have more wealth or are better at doing something than we are. And it will always be that way. We can’t control how beautiful, successful or talented others are. What we can do is avoid comparison—and practice contentment with who we are. For those of us who study yoga, that includes contentment with our asana practice and with our physical limitations.

Lao Tzu, the great sage who wrote the Tao Te Ching, calls contentment “the greatest treasure.” Patanjali Maharishi, author of The Yoga Sutras, a collection of 200 sutras on the teachings of yoga, lists contentment (“santosha”) as one of the qualities we should aspire to attain. In Sutra 2.32, Patanjali says, “By contentment, supreme joy is gained.” Being content means being as we are without looking to external things for our happiness.

The Trouble With Discontentment

How often do we catch ourselves complaining about how we look or feel or how poorly we think we’re doing in our yoga practice? How often are we frustrated when our bodies won’t bend the way we think they should? Let’s be honest: How chronic is our need to be different from the way we are?

In hatha yoga, we have a wonderful opportunity to practice contentment. However, many people use yoga as a way to compete with others or to drive themselves to achieve their ideas of perfection. Open a yoga magazine or any book on yoga, and you’ll see perfect bodies pictured in perfect yoga asanas, or positions. I often ask my students, “Why do you think these people were chosen to be photographed?” The answer is simple: They were good at it! It is a shame that even in the practice of yoga, rooted in the yamas (restraints or don’ts) and niyamas (observances or dos), we are still held to the often unattainable goal of achieving perfect form.

Of course we like to be good students and we don’t want to be lazy, but comparing ourselves negatively with others and obsessing about what we think is wrong with us is not good practice—it simply reinforces our discontent. The true purpose of doing asanas is to learn about ourselves and understand the very real physical reasons for our own individual expressions of poses. Ultimately, as we learn to be content with our bodies we can become more aware of our spiritual nature and our reason for being here: to serve.

Respecting Our Limitations

The sciences of human anatomy, biomechanics and neurophysiology have given us multiple reasons why it is impossible for everyone to achieve the same positions in yoga. A number of these reasons are genetic! For example, some people are naturally thin or are born with lots of joint play. Such qualities come from having specific parents, not from years of yoga.

What if you were born with a femoral head that did not allow for much contact surface in the acetabulum (the rounded cavity of the pelvis that receives the head of the femur to form the hip joint)? A pose like lotus, or padmasana, could be physically impossible for you to accomplish without destroying your hip or associated knee joint. Without this information, you might practice and practice to achieve that position—but succeed only in lessening your given range of motion by going against your normal function.

In yoga, our abilities to achieve certain poses are limited by many factors other than physical traits received at birth. In response to overuse, injury, stress or trauma (either physical or emotional), the body tightens up to avoid entering ranges it cannot control. We must respect this, as our nervous system knows everything that is going on within us at any moment. The body does not make mistakes. All we can do is be content with whatever range we have today. Many injuries are brought about when we decide to go against our bodies and push just a little harder than they can go. If a position we are working with is not one we practice in our life, we can expect our ability to be limited.

Muscles are supposed to retain a certain amount of stiffness to maintain joint integrity. Also, they are always under some tension. Muscles adjust their length based on need, to deal with the forces placed on our joints. Many athletes participate in activities that require repetitive joint motions under a specific force. Their tissues adapt to this stimulus, adjusting in length and stiffness to do what is demanded of them most of the time. We cannot expect avid runners or cyclists to be especially flexible in yoga terms. For the activities they have chosen, why would they need to be?

Also, as we get older many influences—including heredity, environment, culture, diet, exercise, leisure activities and past illnesses—affect how we age. Our cells begin to die faster than they are replaced. Connective tissue gradually stiffens. Organs, blood vessels and airways become more rigid. Changes in the muscle tissue, combined with normal aging changes in the nervous system, cause muscles to have less tone and less ability to contract. They may become rigid with age and lose tone, even with regular exercise. Since we are all aging, we can certainly benefit from practicing contentment with natural changes that take place, while working every day to be healthy.

David Swenson, one of my teachers, says, “The real yoga, you can’t even see.”

Think of two students attempting bow pose, or danurasana. This pose is done in a prone position, with both knees in flexion and both hips in extension. The pose requires trunk extension, scapular retraction and depression, and glenohumeral extension so you can grab the feet and ankles while looking upwards.

Now imagine the two students practicing side by side in a class. Both find that they can’t grab the feet in bow pose. One student quickly throws one arm back to grab the right foot and then repeats the action with the left foot. His breath is labored and his face is flushed, but he is “in the pose.” The other student, who has also noticed that he cannot reach his feet today, decides to rest his arms by his side and work to maintain a position of extension in the shoulders, trunk and hips with his knees in flexion. Technically, he is not “in the pose,” but he is the student who is really doing yoga. He is observing his range and where his body is today, and he is allowing himself to modify the pose. He is learning about patience, acceptance and contentment.

T.K.V. Desikachar, developer of Viniyoga, which tailors the practice to each student’s unique condition, says, “If we want to make this principle of asana practice a reality, we have to accept ourselves just as we are. If we have a stiff back, we have to acknowledge this fact.” Desikachar also reminds us, “If we do not succeed in maintaining a gentle, even, quiet sound (breath), then we have gone beyond our limits in the practice.”

Loving Ourselves As We Are

Can we learn to fall in love with who we are? This includes our lives, our bodies, and our dharma, or purpose. Practicing with contentment teaches us that we really do have everything we need right here, right now. When we are constantly focused on what we don’t have, we only get more of what we don’t have! If most of our thoughts center on not being thin enough, not being strong enough, not being attractive or rich enough, we will continue to experience lack in our lives. Shifting into a vibration of thankfulness changes that.

Let’s learn to recognize and honor our limitations, rather than push past them. Let’s remind ourselves—at the start of our practice and during it—that what is currently happening is perfect, even if we are not as strong as we were yesterday. Then let’s feel proud of our accomplishments and be thankful for all of the wonderful things that we have.

Look around you and see what you have to be content with right here in this moment. Focus on that and watch your stress levels drop and your mood start to lift.

As teachers, we go to asana clinics and learn adjusting techniques that can supposedly be applied to everyone. However, what if the real reason a student is unable to achieve an “ideal” posture is that her central nervous system has decided to limit motion to protect an area of the body? What if there is a bone spur on a shoulder, for example, and achieving full shoulder flexion in downward-facing dog, or adho mukha savasana, is not the ideal position for that person? Since we cannot see inside of joints to tell if there is a meniscal or labral tear, cartilage disruption or scar tissue in the way, do we have the right to push people further? In fact, do we ever ask ourselves, “Why is going further important?”

I have gone to so many yoga workshops where a student was chosen to demonstrate a pose for everyone else to watch. I’ve always thought, “That is great for him or her, but how does watching this person help me with my hip/knee/shoulder, etc?” How does watching someone perform something better than us teach us how to be content with ourselves? Why do we want more all the time? Isn’t what we have enough?

On September 11, 2001, in New York City, Sri K. Pattabhi Jois led his ashtanga class. Rather than focus on what people had lost and how much sorrow and fear would follow, he simply said, “Samastitihi (Sa-maas-tee-tee-hee),”—which means “Clean the slate,” “Come to this moment” or “Come to the front of your mat,”—and started to inspire his students with his gift of teaching yoga.

Are you offering your gift? Are you able to set aside dissatisfaction, see that you have all you need in this moment and ask the question “How may I serve?”

References

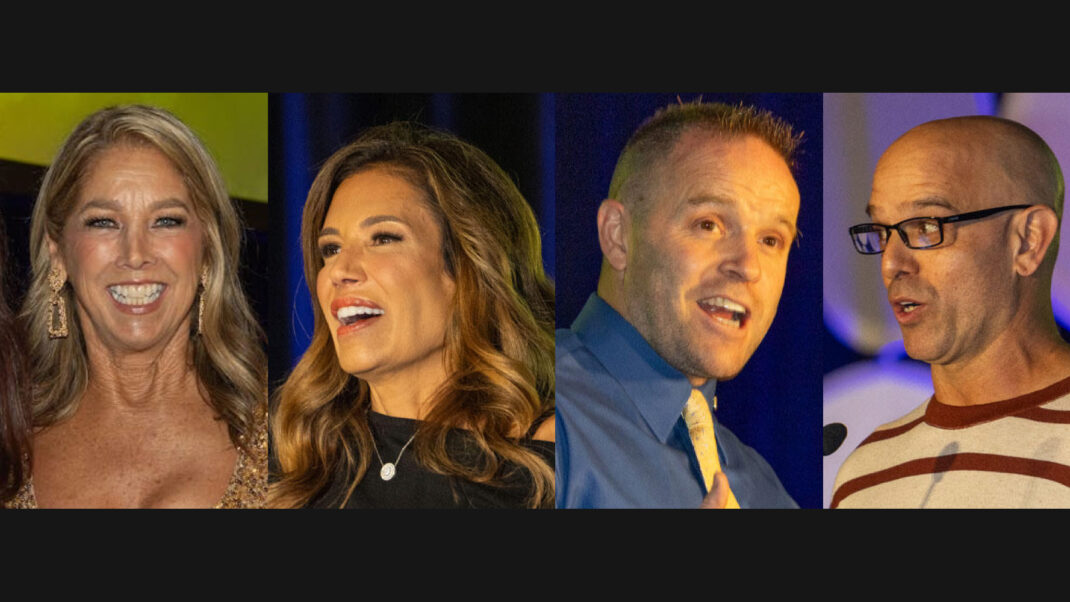

Lauren Eirk

Lauren Eirk is an RTS┬« mastery-level Resistance Training Specialist┬«, a member of the RTS teaching faculty, a Muscle Activation TechniquesÔäó certified specialist, and a certified yoga instructor. She is the creator of the nationally-recognized education program, Yoga Integrated ScienceÔäó (Yoga I.S.┬«).

Certifications: ACE, AEA, AFAA