10 Super Nutrients You’ve Never Heard Of

Be prepared when your clients start asking questions about the promising health benefits of these potent plant compounds.

It is probably safe to say that the terms rutin, hydroxytyrosol and limonene are not currently household words in America. However, news outlets will likely soon be reporting on emerging research that touts the health benefits of these and other plant-based “super nutrients.”

These nutrition powerhouses appear to have many beneficial effects on human health, including heightening immune

response and preventing heart disease and certain cancers (Ullah & Kahn 2008). Because these compounds are readily available from plant foods, they can be easily incorporated into the diet.

This column will look at a group of plant-based super nutrients, commonly referred to as phytonutrients or phytochemicals.

Pondering Polyphenols

Many phytonutrients are classified as polyphenols (Ullah & Kahn 2008). These compounds have been identified in plant foods such as fruits, vegetables, grains, nuts and seeds. Depending on their source and function, polyphenols may be further broken down into subcategories known as bioflavonoids, curcuminoids, anthocyanidins, terpenes and lignans.

Bioflavonoids are pigments that are widely distributed in plants and are responsible for the vibrant colors of many fruits, vegetables and flowers. These compounds seem to function as protective agents against molds, ultraviolet radiation, disease and insects. More and more often, they are being recognized for their powerful antioxidant activity in human cells (Ullah & Kahn 2008).

Also responsible for pigments, curcuminoids are bright yellow polyphenols found in spices, whereas anthocyanidins contribute to the brilliant red and blue coloration of many berries and other fruits, such as plums and grapes.

Terpenes form the building blocks of the essential oils within flowers and herbs used in alternative medicine and aromatherapy. Lignans are plant compounds that appear to promote or block the effects of human estrogen in the body, which may someday play a role in the prevention and treatment of female reproductive cancers.

Health Benefits of Phytonutrients

Evidence that phytonutrients play a protective role in human health is emerging from a variety of laboratory and population studies (U.S. Department of Agriculture [USDA] 2005).

In terms of human growth and development, these nutrients’ essential functions have not yet been identified (unlike those of vitamins and minerals), and clinical deficiencies are still unknown. However, current research suggests that phytonutrients may decrease the risk of developing chronic diseases, particularly cancer and heart disease (Williamson & Holst 2008). Although virtually all phytonutrients function as antioxidants and/or anti-inflammatory agents, each may affect a different aspect of our health.

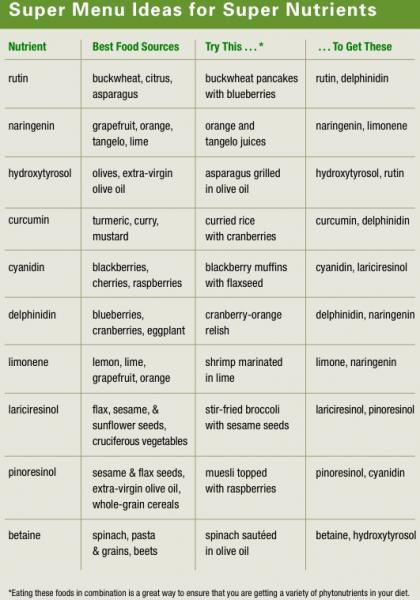

Here is a look at the food sources (see the sidebar “Super Menu Ideas for Super Nutrients”) and benefits of 10 of these super nutrients that you will soon be hearing about in the mainstream press.

Rutin

Rutin, a bioflavonoid with potent anti-inflammatory properties, is primarily found in buckwheat and is also present in varying amounts in asparagus, citrus fruit and tea. Because it has been shown to prevent bruising and swelling and appears to strengthen blood capillaries, rutin shows promise in the prevention and treatment of venous leg disease. Rutin may also block the production of histamine, the substance responsible for allergic reactions in the body. The beneficial effects of rutin appear to be strengthened when it is consumed with foods that are high in vitamin C (Chin & Garrison 2008).

Naringenin

Naringenin is a bioflavonoid found mostly in the juice of grapefruit, oranges and other citrus fruits. Laboratory studies have shown that it blocks damage to DNA in cells, may help regulate blood sugar levels and appears to block glucose production by the liver (Nahmias et al. 2008; Purushotham, Tian & Belury 2009).

Hydroxytyrosol

Hydroxytyrosol is a polyphenol found primarily in olive oil, and also in red and white wine. Animal studies have shown that hydroxytyrosol improves blood lipids, prevents the growth of atherosclerotic plaque and reduces damage to tissue caused by cigarette smoke (Covas et al. 2006). A multicenter clinical trial investigating the effects of olive oil on blood lipids found that consumption of extra-virgin olive oil was linked to higher levels of HDL cholesterol and lower levels of LDL cholesterol (Covas et al. 2006). Hydroxytyrosol may also protect against breast cancer. Although it is difficult to quantify the amounts of hydroxytyrosol in different types of olive oil, the virgin and extra-virgin varieties generally contain much higher levels than refined oils.

Curcumin

Curcumin is a curcuminoid polyphenol found in the spice turmeric, a member of the ginger family often used in Asian and Middle Eastern curries. It is also a food coloring that is added to yellow mustard and a variety of other prepared foods. Curcumin is a strong antioxidant that

reduces inflammation, regulates blood clotting and prevents the growth of

bacteria and fungi. Curcumin may prevent growth of certain bacteria associated with gastric ulcers and cancer (Bengmark, Mesa & Gil 2009). The compound also shows some promise as a preventive agent in the development of Alzheimer’s disease and in preventing tissue rejection after kidney transplantation (Mishra & Palanivelu 2008).

Cyanidin

Cyanidin is an anthocyanidin found in red and blue berries, such as blackberries, cherries, blueberries, cranberries and raspberries; it is also found in plums, grapes and red onions. Animal studies have shown that cyanidin prevents and slows the growth of cancerous skin and lung tumors, and may also protect against cellular damage caused by cerebral, cardiac and liver ischemia (Stoner 2009; USDA 2007). Recent studies have shown that cyanidin may be protective against oral and colon cancer (Stoner 2009; USDA 2007).

Delphinidin

Delphinidin is another powerful anthocyanidin that may prevent the growth of blood vessels that feed cancerous cells, thereby blocking the growth of tumors. Delphinidin is found mainly in blueberries, cranberries, eggplant, grapes and red wine. Because cyanidin and delphinidin are both present in high concentrations in berries, it is difficult to assess their individual effects on health. Therefore, clinical trials are now underway to study the effects of berry consumption on different types of cancers (Stoner 2009; USDA 2007).

Limonene

Limonene is a terpene polyphenol found in the oils of citrus fruits, such as oranges, lemons, limes and grapefruit. Because of its pleasant aroma and low toxicity, limonene is widely

used as a flavor and fragrance enhancer in foods and beverages. Limonene has been shown to prevent and dissolve gallstones and to relieve heartburn and reflux disorder (Sun 2007). First-stage clinical trials have shown that limonene can also slow the progression of breast and colon cancer, relieve the side effects of chemotherapy and prevent the growth of skin cancer (Sun 2007).

Lariciresinol

Lariciresinol is a lignan polyphenol found in a variety of nuts and seeds (e.g., flax, sesame, cashew, sunflower); cruciferous vegetables (e.g., broccoli and cauliflower); tomatoes; and carrots. Lariciresinol is the most common of the lignans found in foods. Epidemiologic studies have shown that high dietary intakes of lariciresinol may protect against breast, ovarian and endometrial cancer (Milder et al. 2005).

Pinoresinol

Pinoresinol is another lignan commonly found in sesame and flax seeds, whole-grain cereals and olive oil. Studies have shown that it has effective anticarcinogenic properties and may be a strong contributor to the low incidence of colon and breast cancer in populations consuming the Mediterranean diet (Milder et al. 2005). Both lariciresinol and pinoresinol seem to reduce the risk of breast and reproductive-tract cancers by blocking the effects of estrogen in the body.

Betaine

Because it is also found in animal foods, betaine is not usually classified as a phytonutrient. However, its health-enhancing effects are similar to those of other plant-based nutrients. Betaine is a derivative of the essential nutrient choline (part of the vitamin B complex) and is found primarily in grains, beets and spinach (and also in red meat). Betaine is essential for many critical physiological functions in the body, including cell reproduction and the breakdown of fats. It has also been shown to reduce high blood levels of the amino acid homocysteine, a known risk factor for heart disease (Cho et al. 2006).

A Word About Supplements

Some of the phytonutrients discussed in this article are now sold in supplement form. However, most health experts

recommend that individuals obtain

phytonutrients through food sources rather than supplements. Many nutrients function synergistically in foods,

exerting different effects this way than when consumed as individual supplements. Phytonutrients extracted from foods and consumed as supplements may have greatly reduced biological

activity or have antagonistic effects in the body. Moreover, although generally considered nontoxic, intake of these substances may be unsafe if consumed in excess by young children, people who have chronic medical conditions and women who are pregnant or breast-feeding.

Because interactions between drugs and many phytonutrients are poorly understood, caution should be used when using supplements in conjunction with prescription medication. For example,

dietary naringenin has been found to interact with certain drugs, such as calcium channel blockers, which is why intake of grapefruit juice is often restricted in individuals taking these medications.

In addition, excessive consumption of some super nutrients may be harmful to vulnerable individuals who combine phytochemical-rich food sources and supplements. For example, Indian mulberries, commonly known as noni, are particularly rich in rutin. Potassium levels are extremely high in noni juice, and drinking large amounts of it may be damaging to individuals with kidney disease.

How to Optimize Phytonutrient Intake

There is little doubt that consuming phytonutrients from a balanced variety of plant foods is desirable for most individuals. The question arises: What intake levels of these super nutrients are optimal for health?

Although their dietary sources have been identified, it has been difficult to quantify the precise amounts of these super nutrients in foods. In general, the phytonutrient content of fruits and vegetables is extremely variable; it depends on climate, soil type, growing conditions and degree of processing. In addition, the bioavailabity of many phytochemicals is not well understood.

As a result, it is hard to define the optimal intake levels for these plant nutrients. In light of this, some experts recommend taking the “Five-A-Day” approach (i.e., eating a variety of five fruits and vegetables daily) as a practical guideline for obtaining adequate amounts of phytonutrients in our diets (Williamson & Holst 2008).

In addition to following the Five-A-Day plan, here are some other easy ways to increase levels of super nutrients in your daily meals:

- Choose fruits and vegetables with deep blue, red and purple colors.

- Eat fruits and vegetables in a variety of forms (raw, fresh and cooked) to aid nutrient absorption.

- Use extra-virgin olive oil in food preparation as often as possible.

- Consider both quantity and quality when choosing fruits and vegetables. A handful of fresh blueberries offers more super nutrient value than a cup of applesauce.

- Add flax and sesame seeds to yogurt, breakfast cereals and salads.

For a list of menu ideas that will increase your phytonutrient consumption, see the sidebar “Super Menu Ideas for Super Nutrients.

References

.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0212-16112

009000300003&lng=en&nrm=iso; retrieved Sept. 8, 2009.

Chin, C.K., & Garrison, S.A. 2008. Functional elements from asparagus for human health. XI International Asparagus Symposium, International Society for Horticultural Science 776. www.actahort.org/books/

776/776_27.htm; retrieved July 18, 2009.

Cho, E., et al. 2006. Dietary choline and betaine assessed by food-frequency questionnaire in relation to plasma total homocysteine concentration in the Framingham Offspring Study. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 83, 905–11.

Covas, M., et al. 2006. The effect of polyphenols in olive oil on heart disease risk factors: A randomized trial. Annals of Internal Medicine, 145 (5), 333–41.

Milder, I.E.J., et al. 2005. Lignan contents of Dutch plant foods: A database including lariciresinol, pinoresinol, secoisolariciresinol, and matairesinol. British Journal of Nutrition, 93, 393–402.

Mishra, S., & Palanivelu, K. 2008. The effect of curcumin (turmeric) on Alzheimer’s disease: An overview. Annals

of Indian Academy Neurology, 11 (1),13–19. www

.annalsofian.org/article.asp?issn=09722327;year=2008;volume=11; issue=1;spage=13;epage=19;aulast=Mishra; retrieved Sept. 8, 2009.

Nahmias, Y., et al. 2008. Apolipoprotein B-dependant hepatitis C virus secretion is inhibited by the grapefruit flavonoid naringenin. Hepatology, 47 (5), 1437–45.

Purushotham, A, Tian, M., & Belury M.A. 2009. The citrus fruit flavonoid naringenin suppresses hepatic glucose production from Fao hepatoma cells. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research, 53 (2), 300–307.

Stoner, G.D. 2009. Foodstuffs for preventing cancer: The preclinical and clinical development of berries. Cancer Prevention Research, 2 (3), 187–94.

Sun, J. 2007. D-Limonene: Safety and clinical applications. Alternative Medicine Review, 12 (3), 259–64.

Ullah, M.F., & Kahn, W. 2008. Food as medicine: Potential therapeutic tendencies of plant derived polyphenolic compounds. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, 9, 187–96.

U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), Agricultural Research Service. 2005. About us. PL FAQs. Phytonutrient FAQs. www.ars.usda.gov/Aboutus/docs.htm?docid=4142; retrieved July 18, 2009.

USDA, Agricultural Research Service. 2007. Database for the flavonoid content of selected foods. Release 2.1. USDA national nutrient database for standard reference. Release 2.1. www.ars.usda.gov/Services/docs.htm?docid=6231; retrieved July 18, 2009.

Williamson, G., & Holst, B. 2008. Dietary reference intake (DRI) value for dietary polyphenols: Are we heading in the right direction? British Journal of Nutrition, 99 (Suppl. 3), S55–S58.