Fed Up: Who’s Ensuring America’s Food Safety?

Why there aren't enough cooks in the kitchen keeping our food supply safe.

There seems to be a new food scare every

day. Headlines blare: Multistate

outbreaks of Salmonella

associated with raw tomatoes! Chili sauce linked to botulism cases! Local

stores recall beef patties in fast-food restaurants!

Food-borne pathogens cause about 76 million illnesses among

unsuspecting Americans each year, leading to 325,000 hospitalizations and 5,000

deaths (Mead et al. 1999). Extensive outbreaks are exposing huge flaws in the

U.S. food safety check-and-balance system. Recent high-profile cases illustrate

the nation’s vulnerabilities in areas ranging from how our produce becomes

infested with E. coli

and other contaminants to the risk posed by foods imported from other countries

or tainted by terrorists.

A combination of outdated laws, questionable oversight and

potentially deadly consequences has made food safety a hot-button issue. Even

one of the agencies responsible for food safety recently issued a report saying

it could no longer perform its mandate owing to woefully inadequate resources.

So what is a consumer to do to avoid food-borne illness when

purchasing, preparing or eating food at restaurants or at home? One way is to

stay informed about the dangers and know how to minimize the risks for you and

your family.

America’s Food Safety Risk

In the United

States, the weighty job of food safety oversight is split mostly among three

agencies: the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), which regulates meat

products; the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which oversees produce and

seafood; and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which

monitors and controls outbreaks of food-borne illnesses.

However, many other agencies play some role in food safety:

according to the National Academy of Sciences, “at least a dozen federal agencies

implementing more than 35 statutes make up the federal part of the food safety

system” (Institute of Medicine and National Research Council 1998). Food safety

threats stem from abroad and from home, further straining the government’s

regulatory and oversight capabilities.

The Import Safety Net

The U.S. imports $2 trillion worth of

goods each year (Merle 2007). The FDA, tasked with overseeing the importation

of seafood, fruits and vegetables, inspects only about 1% of incoming shipments

(Merle 2007). Total imports from China, a country well known for its toxic food

products, were expected to reach $341 billion in 2007, up almost 25% from 2006

(Merle 2007). That means a lot of potentially tainted food is now entering the

U.S. food supply.

When the FDA perceives a risk to be particularly high, it issues

an “import alert,” meaning every food shipment is supposed to be held until it passes a laboratory

test. For example, the FDA issued such an alert about Chinese seafood because

of the high risk of contamination from banned drugs and chemicals.

Unfortunately, the Associated Press discovered that 1 in 4 shipments of the

suspect seafood got to grocery store shelves and dinner plates without having

been tested (Pritchard 2007). This shows that even when the risk is high,

gaping holes exist in the nation’s safety net.

Consider the vulnerability of produce imports. Consumer demand

for year-round access to fruits and vegetables has contributed to increased

importation of these items. Research from the Center for Science in the Public

Interest (CSPI) indicates that about 13% of food-borne illness outbreaks and

21% of food-borne illnesses result from contaminated produce, such as lettuce,

salads, melons, sprouts and tomatoes (DeWaal 2007b). While some of the contamination

comes from domestic produce, fruit and vegetable imports from areas with

substandard hygiene practices have sickened thousands of Americans—notably,

those who ate Cyclospora-contaminated

raspberries grown in Guatemala or strawberries infested with hepatitis A from

Mexico.

The Risk at Home

Not all food

safety risks stem from foreign countries. Last year, a Consumer Reports study found that 83% of fresh, whole broiler chickens

purchased throughout the U.S. were contaminated with Campylobacter or Salmonella (Consumer Reports 2007). That was up from 49% in 2003. It didn’t matter if

the chickens were organic or raised without antibiotics; in fact, those

chickens were actually more likely to harbor Salmonella.

USDA inspectors are supposed to check animal carcasses at each

plant and reject those with visible fecal matter, defects or any signs of

illness. Meat and poultry are supposed to be inspected daily. But still, too

much infected meat gets through these safety checks (Consumer Reports 2007).

Despite numerous recent domestic-produce “outbreaks,” the

industry is still mostly unregulated. In the wake of 14 outbreaks linked to

lettuce and tomatoes in 2004, the FDA sent a letter to firms that grow, pack or

ship the implicated products and asked them to “review their current

operations.” After yet another lettuce outbreak, the FDA targeted its letters

to California lettuce growers “recommending” actions to ensure safety (DeWaal

2007b). Clearly, the FDA lacks the authority (and now admits it lacks the

resources) to mandate changes. Thus, as long as recalls are voluntary,

companies are allowed to continue selling suspect produce.

The CSPI has urged the FDA to adopt mandatory restrictions to

improve produce safety. Suggested restrictions include the following:

- manure control to prevent contamination of

crops - regular assessment of water quality at

food-processing plants - strict hygiene practices

- mandatory sanitation procedures

- clear marking of packaging so the sources of

fruits and vegetables can be easily traced in an outbreak (DeWaal 2007b)

A sparse budget limits the FDA’s ability to enforce such

suggestions. Inspections by the agency have declined 81% since 1972; the number

of field staff has decreased 12% since 2003; and inspections are down 47% since

2003 (DeWaal 2007a). Processed-food facilities may see an FDA inspector only

once every 5-10 years. And it’s really no wonder considering the agency’s scant

resources.

In 2006 the FDA experienced a funding shortfall of $135 million,

equivalent to about a 24% budget cut (DeWaal 2007a). While the agency oversees

about 80% of the food supply, it gets about 20% of the funding for food safety.

And it’s not projected to get better: the 2008 budget allows for only $10.6

million in new food safety dollars for the FDA, whereas the USDA, which

oversees about 20% of the food supply, is allocated $104 million for food

safety (DeWaal 2007a). Drastic changes in FDA food surveillance in 2008 seem

highly unlikely.

The Risk of Terrorism

Beyond the

threat of unintentional contamination, the U.S. faces the risk of food terrorism.

According to the World Health Organi┬¡zation (WHO), “the malicious contamination

of food for terrorist purposes is a real and current threat” (WHO 2002).

Acknowledging that risk, in 2003 the FDA evaluated the nation’s vulnerability

to a terrorist act against our food supply. According to the agency’s report,

U.S. troops had discovered hundreds of pages of U.S. agricultural documents

translated into Arabic when searching caves in Afghanistan. The FDA concluded

that there was a high likelihood the U.S. would face an act of agroterrorism

(FDA 2003).

A separate study by the RAND National Defense Research Institute

noted the following U.S. vulnerabilities:

- highly crowded breeding and rearing conditions

for livestock, which heightens the potential that an epidemic could spread and

which limits ability to recognize unusual behavior in an individual animal - overuse and misuse of antibiotics, which

increases livestock susceptibility to disease - insufficient farm and food-related security and

surveillance - inefficient reporting of disease by livestock

producers - lack of veterinarians trained to recognize and

treat unusual livestock diseases (RAND 2003)

The RAND study authors recommended several measures to decrease

the impact of an agroterrorism attack, including modification of vulnerable

food and agriculture practices; education and training; monitoring programs to

track disease; intelligence measures; public awareness and outreach programs;

stockpiling of vaccines and pharmaceuticals; and early-containment procedures

(RAND 2003).

No matter whether the risk comes from outside or inside the

United States, the WHO suggests that measures for managing both intentional and

unintentional outbreaks of food-borne illness be the same: sensible precautions

and strong surveillance and response capacities (WHO 2002).

Current Food Safety Laws

The U.S government recognizes that

changes are necessary to improve food safety. It recently created a panel to

review import safety and called for federal agencies to do a better job of

coordinating oversight and sharing information. Although the government

recommended an increased focus on identifying risky imports, it fell short of

suggesting any of the sweeping changes currently under debate in Congress.

Looking forward, the pending Safe Food Act of 2007 is a House

initiative that would establish a Food Safety Administra­tion to administer and

enforce food safety laws. The Act would require the administration to take

these steps:

- Implement a national food safety program with

particular focus on the hazards associated with inherent risks and processing

of particular foods. - Establish standards for food processing and

food establishments. - Establish a certification system for foreign

governments. - Create requirements for tracing animals from

point of origin to retail sale. - Maintain an active surveillance system.

- Establish a system to monitor contaminants in

food. - Rank and analyze hazards in the food supply.

- Establish a national food safety public

education campaign. - Conduct research pertaining to food safety

(GovTrack.us 2007a).

Unfortunately, the Safe Food Act has been held up in the

Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition and Forestry since February 15, 2007. The

Senate introduced a somewhat similar bill in September 2007, in an effort to

ensure produce safety. At press time, the Senate’s bill has been referred to

the Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition and Forestry (GovTrack.us 2007b).

According to Marion Nestle, PhD, MPH, professor of nutrition,

public health and food studies at New York University and author of Safe Food (University of

California Press 2003), it is unlikely that any of the recommended changes will

be passed anytime soon. “Government safety rules are mired in laws passed in

1906 long before current hazards came into existence. Every time some

government agency tries to update the laws, the industry screams bloody murder

and nothing much gets done,” Nestle told Slow Food USA (Slow Food LA 2004).

Meanwhile, in just 2 months last year (early September to the end

of October), the federal government issued more than 20 food recalls. Several

products contained unlabeled ingredients such as nuts, milk and

eggs—potentially fatal mistakes for the millions of Americans with food

allergies. The other recalls resulted from random testing that revealed a list

of common foods harboring contaminants, such as baking-chocolate squares with Salmonella; tofu and raw

cream infected with Listeria;

Mexican cheese high in Salmonella

and Staphylococcus;

salad and ground beef laced with E.

coli 0157; and canned meat infected with the botulism toxin

(www.recalls.gov). For a look at some of the “riskiest” foods, see the sidebar “Most

Commonly Contaminated Foods.”

Consequences of Contamination

The health consequences from exposure to

contaminated food range from pesky inconveniences like indigestion to serious

injury or death. Special populations most at risk include pregnant women;

infants and young children; older adults; and people with compromised immune

systems.

Salmonella,

Campylobacter and Shigella

are the most likely contaminants, according to the FoodNet surveillance system,

which tracks food-borne illness in 10 states (CDC 2007). Most infections are

self-limiting and resolve without need for antibiotics or treatment other than

aggressive replacement of fluids lost through vomiting and diarrhea. However, E. coli 0157 poses a

particularly severe risk to children, who may contract a serious condition

called hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) following exposure to the pathogen. When

HUS develops, red blood cells are destroyed, kidney function worsens and

platelet count drops substantially. Blood transfusions and kidney dialysis are

often required. HUS can be life-threatening and is usually treated in an

intensive care unit. With intensive care, the death rate for HUS is 3%-5% (CDC

2007).

For more information on food contaminants, their symptoms and how

they are usually treated, see the sidebar “Common Food-Borne Illnesses.”

Alternative Methods to Keep Food Safe

While it is tempting to blame the

government for its failure to protect the food supply, there are other

deserving targets. Time after time, bureaucracy, turf wars, politics and

funding prove to be major barriers to timely food safety reform. Alternative

safety methods, such as food irradiation, are promising but have been slow to

gain public acceptance.

Food

irradiation is the process of using high-energy rays to

destroy organisms with the intent to preserve the nutritional value, taste and

texture of the food product (it should be noted that these characteristics are

altered to varying degrees depending on the amount of irradiation and the type

of food). Importantly, no radioactivity is involved during food irradiation, and

all the evidence suggests that the process is entirely safe. In fact, the CDC

predicts that if irradiation were used on half of the meat and poultry consumed

in the U.S., there would be 900,000 fewer cases of food-borne illness and 352

fewer deaths (Osterholm & Norgan 2004).

Numerous government agencies, scientific and health-related

organizations (national and international) and food-processing groups support

the safety of irradiated food. Researchers who have studied consumers’ reasons

for being wary of irradiated food theorize that the reluctance to embrace the

technology is caused by the dubious terminology (i.e., it sounds scary, as if it’s linked to

radiation), a lack of understanding and a lack of knowledge (Osterholm &

Norgan 2004).

Opportunities for large-scale implementation of food irradiation

are emerging, but until the average consumer feels comfortable with the

technology, experts say that few irradiated foods will be available on store

shelves.

How to Keep Your

Food Safe

While no consumer can fully protect his

or her family from exposure to food-borne illness, several simple precautions

can reduce the risk. From choosing wisely at the grocery store to safely

preparing and storing your food, there are ways to exert some control in safeguarding

against food-borne contamination.

Here are some tips for you and your clients to keep in mind when

selecting foods:

- Check produce for bruises, and feel and smell

for ripeness. Sometimes bruises and other imperfections are signs of a brewing

infection. - Look for a “sell-by date” for breads and baked

goods, a “use-by date” on some packaged foods, an “expiration date” on yeast

and baking powder or a “pack date” on canned and some packaged foods. Most

foods that have passed the sell-by date can be safely consumed up to a few days

after the marked date. However, foods with a marked expiration or use-by date

should be consumed by the stamped date to minimize risk of food-borne illness

and to ensure optimum quality. Play it safe by choosing products with the

latest dates. The pack date is useful only if you know how long a particular

food remains fresh. Generally, canned foods are good for a year after the pack

date, whereas frozen foods are best used within a few months of the pack date. - Ensure that packaged goods are not torn and

cans are not dented, cracked or bulging. Dented cans provide a breeding ground

for botulism. Bulging cans indicate the food is probably already fully infected

with the organism. - Keep fish and poultry apart from other purchases

by wrapping them separately in plastic bags. While fish, poultry and meat

products will later be cooked to a safe temperature to kill bacteria, other

uncooked contaminated purchases can harbor the infection. - Choose refrigerated and frozen foods last, right before checking

out. Make sure all perishable items are refrigerated within 2 hours of

purchase. Freezing or cold temperatures stop or greatly reduce the growth rate

of micro-organisms. However, once products start to warm, bacteria rapidly

multiply.

Consumers may also want to pay special note to where products were processed

and packaged. Generally, foods from countries with lenient food safety

requirements—such as China and many developing countries—pose increased risk.

The 2002 Farm Bill would have required that all beef, lamb, pork, fish,

shellfish, perishable agricultural commodities and peanuts show country of origin on their

labels. Unfortunately, President Bush has delayed implementation of this

requirement for all these commodities except for fish and shellfish until at

least September 2008 (USDA 2007).

Proper Food Preparation & Storage

In a section

devoted to food safety, Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2005 (USDHHS and USDA 2005) offers several simple tips on handling, preparing and storing food safely to reduce exposure to food-borne illnesses. Although it is possible that a contaminated food can enter the

marketplace, adhering to these recommendations makes it less likely that microbes will have the opportunity to cause an infection.

- Wash hands often with warm water and soap for

at least 20 seconds. This is the single most important defense against

microbial infection. - Clean hands and food contact surfaces

thoroughly. - Wash fruits and vegetables before eating or

cooking them. Do not wash

meat or poultry, as washing can spread infection. - Separate raw, cooked and ready-to-eat foods

while shopping, preparing and/or storing foods. - Cook foods to a safe temperature to kill

micro-organisms (bacteria grow most rapidly between 40 and 140 degrees

Fahrenheit, or between 4.4 and 60 degrees Celsius). - If you are pregnant, do not eat deli meats and

frankfurters unless they have been reheated to steaming

hot, to avoid the risk of listeria. - Refrigerate perishable food within 2 hours of

purchase and defrost foods properly (i.e., in the refrigerator, not on the

table counter). Eat refrigerated leftovers within 3-4 days. - Avoid raw (unpasteurized) milk or any products

made from unpasteurized milk; raw or partially cooked eggs or foods containing raw

eggs; raw or undercooked meat and poultry; unpasteurized juice; and raw

sprouts. This is especially important for infants and young children, pregnant

women, older adults and those with compromised immune systems. These groups are

also advised to avoid raw or undercooked fish or shellfish.

Wrapping It All Up

Food safety in

the United States appears to be mired in a web of politics and a battle for

federal funding. Despite a growing number of food-borne illness outbreaks, few

large-scale policy changes have been implemented to reduce the risks to our

food supply.

As a consumer, you ultimately have the responsibility to minimize

your own food safety risk at home and to demand that the federal government do

everything it can to ensure food safety within and across our borders.

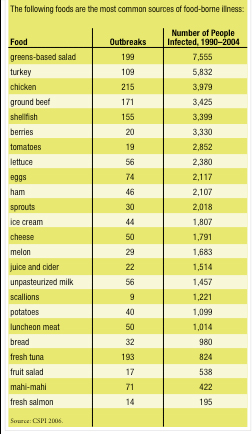

SIDEBAR: Most Commonly Contaminated Foods

SIDEBAR: Common Food-Borne Illnesses

SIDEBAR: Additional Resources

- Center for Science in the Public Interest, www.cspinet.org. A nonprofit health advocacy organization focusing on food safety, nutrition and alcohol issues. Maintains a database of food recalls and food safety information.

- FDA and USDA Recall Information, www.recalls.gov. Gives the latest on recalled foods.

- Fight Bac! www.fightbac.org. Provides information and resources that can help consumers make smart choices to decrease risk of food-borne illness.

- Food & Water Watch, www.foodandwaterwatch.org. A grassroots environmental health organization working to improve food safety through public and policymaker education, lobbying, media and Internet activism.

- FoodNet Surveillance System of the CDC, FDA and USDA, www.cdc.gov/enterics/. Produces an annual report on the incidence of food-borne illnesses in 10 states.

- Foodsafety.gov, www.foodsafety.gov. Provides the latest headlines, recalls, safety information, alerts and advice related to food safety.

- Medline Plus, Food Safety, www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/foodsafety.html#cat59. Offers links to websites with credible information on various food safety topics.

- Safe Food by Marion Nestle, PhD, MPH (University of California Press 2003). Presents an interesting look at the politics behind food safety in the U.S.

Natalie Digate Muth, MPH, RD, is a

registered dietitian and an ACE-, ACSM-, and NSCA-certified fitness

professional. She is currently pursuing a medical doctor degree at the

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She is also an ACE master trainer.

References

Center for Science in the Public Interest (CSPI). 2006.

Fear of fresh: How to avoid food borne illness from fruits & vegetables. Nutrition Action Healthletter, 33

(10), 1-6.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2007.

FoodNet surveillance. www.cdc.gov/foodnet/surveillance.htm; retrieved Nov. 1,

2007.

Consumer

Reports. 2007. Dirty birds: Even premium chickens harbor dangerous

bacteria. www.consumerreports.org/cro/food/food-safety/chicken-safety-1-07/overview/0107_chick_ov.htm;

retrieved Nov. 1, 2007.

DeWaal, C.S. 2007a. CSPI testimony on the safety of

imported foods and ingredients.

www.cspinet.org/foodsafety/Import_FDA_050807.pdf; retrieved Nov. 1, 2007.

DeWaal, C.S. 2007b. Ensuring safe produce. Public hearing

on safety of fresh produce, April 13, 2007.

www.cspinet.org/foodsafety/FDA_Hearing_0407.swf; retrieved Nov. 1, 2007.

GovTrack.us. 2007a. S.654: Safe Food Act of 2007.

www.govtrack.us/congress/bill.xpd?bill=s110-654; retrieved Nov. 1, 2007.

GovTrack.us. 2007b. S. 2077: A bill to establish a

program to assure the safety of fresh produce intended for human consumption,

and for other purposes. www.govtrack.us/congress/bill.xpd?bill=s110-2077; retrieved

Nov. 1, 2007.

Institute of Medicine and National Research Council.

1998. Ensuring Safe Food: From

Production to Consumption. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Mead, P.S., et al. 1999. Food-related illness and death

in the United States. Emerging

Infectious Disease, 5 (5), 607-25.

Merle, R. 2007. Panel urges more scrutiny over imports. Washington Post (Sept. 11).

www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/09/10/AR2007091002409.html;

retrieved Nov. 1, 2007.

Nestle, M. 2006. The spinach fallout: Restoring trust in

California produce. The San Jose Mercury News

(Oct. 22). www.foodpolitics.com/pdf/spinachfal.pdf; retrieved Nov. 1, 2007.

Osterholm, M.T., & Norgan, A.P. 2004. The role of

irradiation in food safety. The

New England Journal of Medicine, 350 (18), 1898-1901.

Pritchard, J. 2007. Holes in the safety net. San Diego Union-Tribune (Aug.

8).

RAND National Defense Research Institute. 2003.

Agroterrorism: What is the threat and what can be done about it?

http://rand.org/pubs/research_briefs/RB7565/RB7565.pdf; retrieved Nov. 1. 2007.

Recalls.gov. www.recalls.gov/; retrieved Oct. 31, 2007.

Slow Food LA. 2004. Q&A with Marion Nestle.

www.slowfoodla.com/archives/000274.html; retrieved Nov. 1, 2007.

U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). Agricultural

Marketing Service. 2007. Country of origin labeling. www.ams.usda.gov/cool/;

retrieved Nov. 25, 2007.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S.

Department of Agriculture (USDHHS & USDA). 2005. Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2005. www.health.gov/dietaryguidelines;

retrieved Oct. 31, 2007.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 2003. Risk

assessment for food terrorism and other food safety concerns.

www.cfsan.fda.gov/~dms/rabtact.html; retrieved Nov. 1, 2007.

World Health Organization (WHO). 2002. Terrorist threats

to food: Guidelines for establishing and strengthening prevention and response

systems. www.who.int/foodsafety/publications/fs_management/terrorism/en/;

retrieved Nov. 1, 2007.

Natalie Digate Muth, MD, MPH, RD

"Natalie Digate Muth, MD, MPH, RDN, FAAP, is a board-certified pediatrician and obesity medicine physician, registered dietitian and health coach. She practices general pediatrics with a focus on healthy family routines, nutrition, physical activity and behavior change in North County, San Diego. She also serves as the senior advisor for healthcare solutions at the American Council on Exercise. Natalie is the author of five books and is committed to helping every child and family thrive. She is a strong advocate for systems and communities that support prevention and wellness across the lifespan, beginning at 9 months of age."