More Paths to Exercise Recovery

High-intensity exercises place a premium on alternative recovery options for rest, healing and growth to avoid overtraining.

| Earn 1 CEC - Take Quiz

When it comes to balancing your training program, your mindset should be, “Tomorrow’s workout begins with your recovery from today’s.” Exercise recovery heals the pounding, twisting and tearing of physical activity. A well-thought-out strategy for recovery is becoming ever more crucial with the rising popularity of high-intensity workouts featuring barbells, kettlebells, heavy medicine balls, explosive plyometrics and anaerobic interval training.

These methods produce results, but there is such a thing as too much exercise. Hitting it too hard for a day produces temporary soreness. Keeping up that intensity for too long can produce overtraining syndrome (OTS), which causes a raft of problems (see “Metabolic Damage From Overtraining” and “Symptoms and Effects of Overtraining Syndrome,” below). Teaching your clients alternative recovery methods can help them stay on track while reducing the risk of overtraining.

That means teaching them the full scope of recovery—optimal hydration, proper nutrition, increased circulation and healthy sleep patterns—to help the body heal. By identifying the best recovery strategies for each client’s needs, you set yourself apart as a knowledgeable fitness professional who understands the importance of what happens after people leave the gym. That’s good for business and great for clients.

Addressing the Threat of Overtraining

We all need rest because it helps the body put hormones and satellite cells to work repairing damaged tissues, restoring spent energy to muscle cells and removing metabolic byproducts that can be recycled into more fuel or eliminated from the body (Kellmann 2010).

Most group workouts or individual client sessions last 30–60 minutes and usually do not impose enough stress to require specific interventions beyond eating right and getting enough sleep. However, weightlifting to the point of fatigue or doing high-intensity interval training that leads to breathlessness can cause metabolic damage to body tissues. Over time, the damage can accumulate and cause OTS.

Technically speaking, OTS is a quantifiable loss of performance in a specific sport. If your clients or group workout participants do not use quantitative performance metrics like running a distance in a certain time or lifting predetermined weights in their workouts, it can be difficult to say if they are experiencing OTS. Moreover, the syndrome can’t be diagnosed accurately without first ruling out iron deficiency with anemia and organic or infectious diseases (Hausswirth & Mujika 2013).

Since diagnosis is a doctor’s job, you’re far better off encouraging clients to adopt specific recovery strategies that are affordable, convenient and easy to stick with. That way, you can limit accumulation of metabolic fatigue and avoid OTS in the first place.

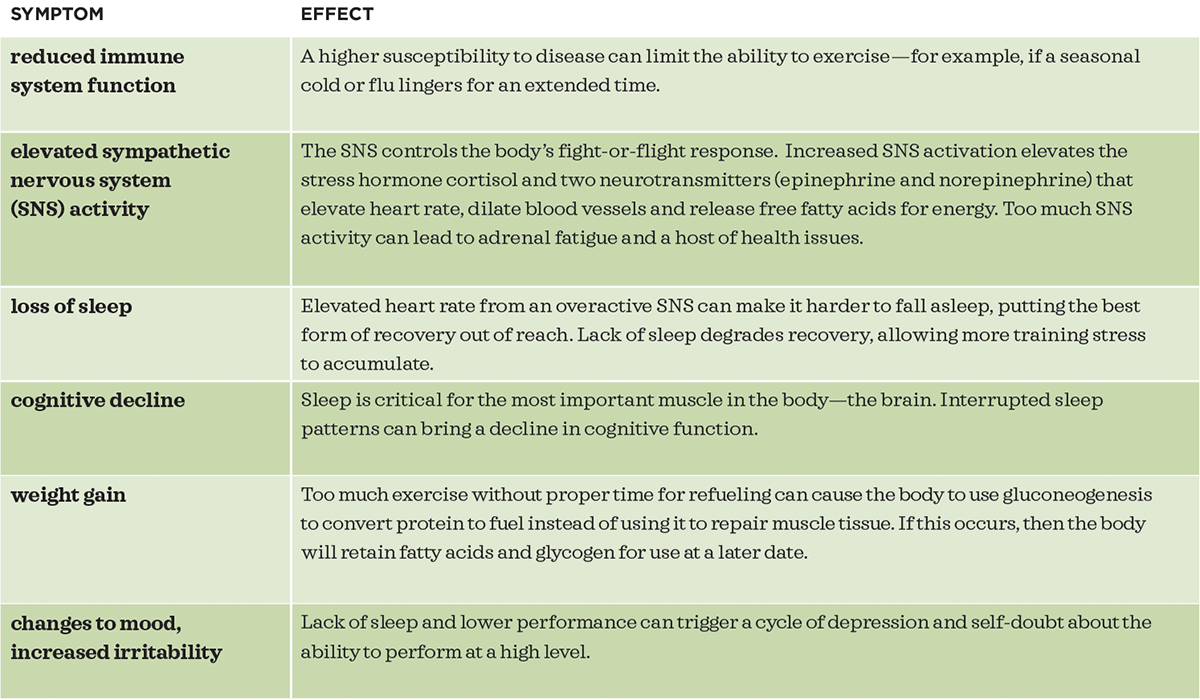

SYMPTOMS AND EFFECTS OF OVERTRAINING SYNDROME

Doing too much high-intensity exercise without adequate rest or working out too many days in a row without a break can lead to overtraining syndrome, especially if other stressors are present (Hausswirth & Mujika 2013).

OTS is associated with chronic fatigue, decreased physical performance, mood changes, neuroendocrine system imbalances and frequent illnesses (MacKinnon 2000).

Here’s a look at the effects of common OTS symptoms:

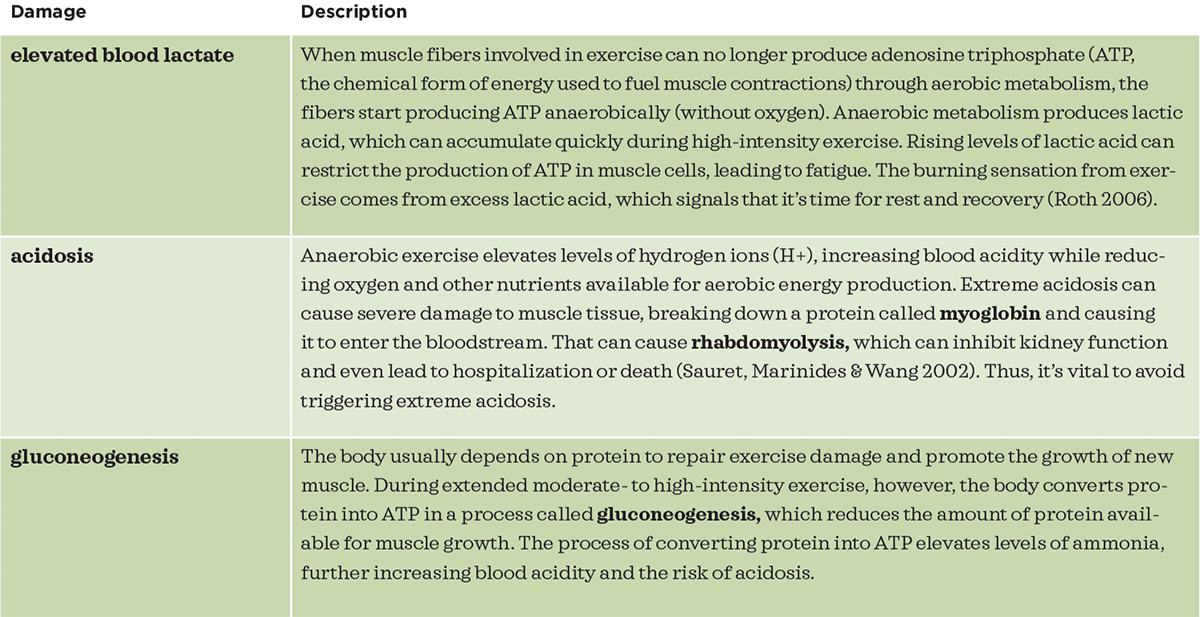

METABOLIC DAMAGE FROM OVERTRAINING

Overtraining can produce excessive metabolic damage to muscle tissue. In the short run, excessive exercise causes pain a day later in a phenomenon called delayed-onset muscle soreness, or DOMS (WebMD 2018). In the long run, hitting it too hard can cause overtraining syndrome, which can degrade athletic performance. Effective recovery strategies speed the body’s natural repair process, reducing soreness and allowing clients to continue exercising without interruption.

These are some of the most common forms of overtraining damage:

Recovery Fundamentals in Brief

Exercise damages the body’s muscular, skeletal, cardiorespiratory and endocrine systems, triggering healing and adaptions during recovery. For all the health benefits of exercise, each type of training imposes different kinds of harm. Resistance training, for instance, improves functional strength but also applies mechanical forces that cause tears in muscle and connective tissue. Running, on the other hand, pumps vital oxygen and nutrients into working muscle and removes hazardous metabolic byproducts, but it also stresses the heart, lungs, muscles and joints.

Like many kinds of exercise, running creates mechanical stresses in multiple directions: top-down from gravity and bottom-up from ground reaction forces. Movements like yoga place diverse stresses on joints and muscles as exercisers go through a range of poses and positions.

Recovery can be a couple of minutes between weightlifting sets or a couple of days between intense workouts. Either way, the pauses between exercise bouts set off a range of processes that make recovery as valuable as the activity itself.

See also: Recovery: The Rest of the Story

8 Alternative Exercise Recovery Techniques

Lots of trainers are helping clients speed up their recovery via methods such as myofascial release with foam rollers, nutrient timing and good sleep hygiene. These work especially well for clients who enjoy high-intensity exercise (and probably do too much of it).

While these techniques are tried-and-true, affordable and easy-to-do, the rising enthusiasm for hard-hitting exercise routines has spawned a growing interest in alternative recovery techniques. Let’s take a look at eight of them. (Note that some may have reams of peer-reviewed research demonstrating their benefit, while the value of others is based on anecdotal evidence. It’s critical to understand the difference.)

1. CRYOTHERAPY CHAMBER TREATMENTS

Ice baths promote recovery by increasing circulation, but some people don’t want to spend up to 20 minutes in ice water to receive this benefit. The alternative is to visit a cryotherapy freeze chamber, which rapidly reduces air temperature to below °110 degrees Celsius °160 degrees Fahrenheit).

One theory holds that cold shocks the system, causing blood to move to the center of the body and protect the vital organs. Removing the cold causes blood to return to the extremities, delivering oxygen and nutrients for tissue repair. A second theory is that rapid application of cold causes the sympathetic nervous system to release epinephrine and cortisol, which can increase circulation and help to remove metabolic byproducts (Hausswirth & Mujika 2013).

2. COMPRESSION CLOTHING

Wearing compression clothing before and after a tough workout is a relatively new strategy that may reduce the time needed for optimal recovery. Pressure from the tight clothing can theoretically improve circulation, which helps remove metabolic byproducts from muscle and promotes the flow of oxygenated blood to assist in repairing and rebuilding tissue.

Compression clothing can also elevate tissue temperature, reducing soreness. While there has been a variety of research on the effectiveness of compression clothing, there is no overwhelmingly conclusive evidence for or against it. One study observed no significant performance differences from wearing compression clothing (Duffield et al. 2008). However, later studies found that wearing such clothing during and after exercise resulted in small to moderate changes in performance and recovery (Kraemer 2010; Born, Sperlich & Holmberg 2013).

3. CUPPING

Cupping is a Chinese medicine practice that places small glasses or bowls directly on the body to create suction on the skin and tissues directly underneath. Supporters assert that pressure from the vacuum increases localized circulation and produces an anti-inflammatory response, both of which promote healing that is essential to recovery (Weinberg 2016).

The pressure may be uncomfortable, and the practice results in large circular welts like those observed on American swimmer Michael Phelps during the 2016 Olympics.

4. CANNABINOID-RELATED PRODUCTS

Endocannabinoids are lipid molecules in the body that can be produced in response to exercise. Because they can reduce pain and promote feelings of euphoria, endocannabinoids are suspected of being partly responsible for the postexercise high that people often experience (Tantimonaco et al. 2014).

The cannabinoid system helps to regulate homeostasis and influences appetite, mood, hormones, sleep, immune function and pain. Cannabidiol (CBD) is a nonpsychoactive ingredient in cannabis (Pagotto et al. 2006) that may reduce postexercise inflammation by suppressing cytokine production while promoting sleep. CBD can be sold without restrictions because it is unrelated to tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the psychoactive agent released during cannabis consumption.

Many companies marketing products that contain CBD say it can reduce pain and inflammation, thereby promoting recovery. Anecdotal evidence from ardent users suggests there may be benefits, but research supporting those claims is extremely limited.

5. INFRARED SAUNAS

Unlike traditional saunas that use rocks or metal heating elements, infrared saunas heat with electromagnetic lamps (Hausswirth & Mujika 2013). An infrared sauna elevates tissue temperature, which can increase circulation to promote recovery. Infrared rays produce heat that molecules can partially absorb. Because the heat affects cells directly, infrared saunas operate at a lower temperature, allowing for a more comfortable, yet beneficial, experience.

6. IMMERSION TANKS

Immersion in water tanks is being promoted as a form of recovery. While immersion may prove beneficial, the equipment can be expensive and difficult to access for the average exerciser.

The principle behind immersion is that water pressure is higher than air pressure and can promote blood flow back to the heart while supporting fluid exchange between capillaries and muscle tissue. Alternating between hot- and cold-water immersion may promote circulation through the dilation and constriction of blood vessels, but, again, this method may not be an easily accessible recovery option (Hausswirth & Mujika 2013).

7. PERCUSSION GUNS

Applying rapid compressive force against muscle tissue can provide a number of benefits, including increasing circulation, breaking up collagen fibers, reducing muscle tightness and promoting localized recovery, according to Brian Bettendorf, MS, MSM, a San Francisco-based exercise physiologist who has collaborated with a company that manufactures percussion guns. “Vibration training in general has a number of neurophysiological effects, including minimizing pain sensation and reducing neural drive in muscle fibers, allowing them to lengthen,” he says. “A percussion gun allows the user to apply the vibrations where they can have the greatest effect.”

Percussion guns have become more affordable and easier to buy, making them a popular recovery tool. There is research on the benefits of vibration training—a literature review found that standing on a vibrating platform can result in significant strength gains (Marin & Rhea 2010). Extrapolating from this research, it is feasible that localized vibration stimulus could provide similar benefits, but much more research is needed before this hypothesis can be supported.

8. PICKLE JUICE

Losing sodium from sweat can degrade exercise performance. Sports drinks provide sodium, which can help muscle cells absorb water more effectively, but they also contain calorie-rich glucose. Recently, athletes have begun drinking the water from bottles containing pickles, cherries or beets. The idea is that this water’s high sodium content can promote recovery by speeding up rehydration.

Again, this is a relatively new concept, so evidence is limited. McKenney and colleagues (2015) saw no significant changes in plasma sodium up to 125 minutes after drinking pickle juice. Likewise, Miller, Mack & Knight (2009) found that ingesting pickle juice did not cause significant changes to electrolyte concentrations in blood plasma. The distinct flavor of pickle juice may make this recovery method best left to personal preference.

Coach the Workout Instead of Doing the Workout

An unfortunate side effect of working in the fitness industry is your own risk of overtraining syndrome, which can lead to burnout and job dissatisfaction.

Of course, it’s exciting to lead workouts that help others improve their lives.

But physically doing every class you teach—especially HIIT formats—can be physiologically demanding enough to cause overtraining. Yes, instructors must be fit, but you still need a recovery strategy. The best approach is to stop doing the classes you teach and focus on coaching clients through the workout.

“I think it’s important for fitness professionals to realize that they are role models,” says Irene Lewis-McCormick, 2018 IDEA Fitness Instructor of the Year and a coach at Orange Theory Fitness® in Des Moines, Iowa. “Daily high-intensity or long-duration training held up to participants as some example of what they, too, should be doing is an outdated and, frankly, egocentric model of being an instructor.

“It is important to lead by example,” she says. “If an instructor is constantly exercising both during and after group fitness classes, then he or she is not acting as a good role model for clients and class participants. When instructors coach classes instead of doing them and talk about the benefits of postexercise recovery, it is an opportunity to educate members on proper self-care as it relates to exercise.”

For example, if you’re teaching an indoor cycling class off the bike, mention that it’s a rest day for you and you don’t need to do the work to ensure that riders meet their goals. Setting an example by modeling healthy behavior can help convey to the people you influence that exercise involves more than what happens in the gym.

What If a Client Feels Sore the Day After a Workout?

Recovery doesn’t just mean resting after exercise. It can mean staying somewhat active while healing from a tough workout.

The client who feels excessive soreness the day after an intense exercise session may be tempted to skip the next workout. That’s expected, given that it can take 24–72 hours to fully recover from a physically demanding workout. But keep this in mind: One effective way to promote recovery is through more exercise—specifically, low-intensity activity that elevates the heart rate slightly above normal, delivering more oxygen, nutrients and healing hormones to damaged muscle fibers, while removing unnecessary metabolic byproducts.

You can provide active recovery via low-intensity, steady-state exercise like walking or cycling at a comfortable pace, where breathing is only a little faster than normal, or via a series of body-weight movements in a gentle yoga sequence or tai chi flow. About 15–20 minutes of lower-intensity exercise can serve as a regeneration workout because it promotes recovery that brings muscle growth.

A TIP TO PREVENT SORENESS

Here’s a way to keep clients from getting sore: Ask what they have planned tonight before you start their workout. If their evening plans include a concert or party that could degrade the quality of their sleep, consider reducing the workout’s intensity level. After all, less sleep means less healing from a tough workout.

On the other hand, if clients plan to relax on the couch and you feel they’ll get enough sleep for optimal recovery, then consider increasing the intensity level.

Honing Your Exercise Recovery Strategy

Resting after a hard workout allows muscles to replace glycogen and adenosine triphosphate, which fuel activity during exercise. Exercising too frequently may not give the body enough time to rest and replace energy burned while working out.

A strong focus on recovery is not required for low- to moderate-intensity sessions that do not overstress body tissues or deplete glycogen stores. A recovery strategy becomes crucial when workouts last longer, get more intense or include explosive movements. Moreover, recovery strategies like nutrient timing can provide a quantifiable benefit, such as delivering a specific amount of carbohydrates to replace those used during exercise. By contrast, compression clothing and cannabidiol products may help you feel better without providing a specific, measurable result.

Some nontraditional methods are so new that there isn’t much peer-reviewed research on them. Often, they’re popular because of an extensive variety of anecdotal support from people claiming to feel the benefits. Whether you’re using traditional or alternative recovery tactics, you need to be improving circulation in order to remove waste from muscle and to deliver new oxygen and nutrients for building new tissue.

Determining the best types and amounts of exercise for each client’s needs usually requires trial and error. The same is true for recovery strategies. As you go through your fitness toolbox to find the best equipment and methods for each individual, remember that exercise is only one part of the equation. To be the best resource for your clients, you also have to coach them on the right recovery methods for their needs after the workout.

See also: Self-Care: Managing the Damage

References

Born, D.P, Sperlich, B., & Holmberg, H.C. 2013. Bringing light into dark: Effects of compression clothing on performance and recovery. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 8 (1), 4–18.

Duffield, R., et al. 2008. The effects of compression garments on intermittent exercise performance and recovery on consecutive days. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 3 (4), 454–68.

Hausswirth, C., & Mujika, I. 2013. Recovery for Performance in Sport. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Hoffman, J. 2014. Physiological Aspects of Sport Training and Performance. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Kellmann, M. 2010. Preventing overtraining in athletes in high-intensity sports and stress/recovery monitoring. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 20 (2 Suppl.), 95–102.

Kraemer, W.J., et al. 2010. Effects of a whole body compression garment on markers of recovery after a heavy resistance workout in men and women. The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 24 (3), 804–14.

Kraemer, W.J., Fleck, S.J., & Deschenes, M.R. 2012. Exercise Physiology: Integrating Theory and Application. Philadelphia: Williams & Wilkins.

MacKinnon, L.T. 2000. Overtraining effects on immunity and performance in athletes. Immunology and Cell Biology, 78 (5), 502–9.

Marin, P.J., & Rhea, M.R. 2010. Effects of vibration training on muscle strength: A meta-analysis. The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 24 (2), 548–56.

McKenney, M.A., et al. 2015. Plasma and electrolyte changes in exercising humans after ingestion of multiple boluses of pickle juice. Journal of Athletic Training, 50 (2), 141–46.

Miller, K.C., Mack, G., & Knight, K.L. 2009. Electrolyte and plasma changes after ingestion of pickle juice, water, and a common carbohydrate-electrolyte solution. Journal of Athletic Training, 44 (5), 454–61.

Pagotto, U., et al. 2006. The emerging role of the endocannabinoid system in endocrine regulation and energy balance. Endocrine Reviews, 27 (1), 73–100.

Roth, S.M. 2006. Why does lactic acid build up in muscles? And why does it cause soreness? Scientific American. Accessed Dec. 17, 2018: scientificamerican.com/article/why-does-lactic-acid-buil/.

Sauret, J.M., Marinides, G., & Wang, G.K. 2002. Rhabdomyolysis. American Family Physician, 65 (5), 907–12.

Tantimonaco, M., et al. 2014. Physical activity and the endocannabinoid system: An overview. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 71 (14), 2681–98.

WebMD. 2018. Sore muscles? Don’t stop exercising. Accessed Dec. 17, 2018: webmd.com/fitness-exercise/features/sore-muscles-keep-exercising#1.

Weinberg, C. 2016. Can cupping really speed post-workout recovery? Accessed Dec. 17, 2018: vocativ.com/news/350152/cupping-recovery/index.html.

Pete McCall, MS

Pete McCall, MS, is the host of the All About Fitness podcast, and the author of Smarter Workouts: The Science of Exercise Made Simple as well as several articles and textbook chapters about exercise physiology. Pete holds a master’s degree in exercise science and has been educating fitness professionals since 2002. Currently, Pete lives in Carlsbad, California, where he is a consultant for Core Health & Fitness, Terra Core Fitness, 24 Hour Fitness and the American Council on Exercise, and a coach for the Coastal Dragons rugby club.