Complex Training: Pairing for Power

Maximize your time with athlete clients by using the retro approach of complex training that's come back into favor.

If you work with athletes, you’ve likely run into the challenge of how to incorporate power components into their already-packed training schedules. Whether you’re working with a clutch outfielder, a center or a lineman, your client’s athletic skills need refinement, and power is one aspect that requires attention. Trainers typically program resistance training to develop strength and plyometric drills to improve speed. However, team and endurance athletes seldom have time to execute both workouts in addition to doing regular practice sessions. A solution is available: To make the most of the time in the gym, trainers are taking a second look at complex training (CT), which became popular in the 1970s after Russian sports scientist Yuri Verkhoshansky coined the phrase (Ali 2017).

CT fell out of favor after undergoing some scrutiny. Nonetheless, recent reviews find that complex training may indeed have a role in training the modern athlete.

What Is Complex Training?

CT combines high-resistance strength training with low-resistance plyometric drills, performed by the same muscle group, during a single workout. The reasoning is that the strength training, while causing muscle fatigue, also improves the muscle’s ability to perform—and thus benefit from—plyometric exercises. The mechanism that enhances the muscle’s readiness to make the most of plyometrics is post-activation potentiation (PAP).

Sports scientists define PAP as “the phenomenon by which acute muscle force output is enhanced as a result of contractile history and is the premise upon which ‘complex training’ is based” (Robbins 2005). As it moves against resistance, the muscle fatigues, but, after a brief rest, it also “wakes up.” Think of it this way: The muscle tires from the heavy load but must continue to work for the plyometric activity. Therefore, the body calls in backup to get the job done, recruiting additional neurons to stimulate extra muscle fibers more quickly and with better coordination. After the conditioning activity, the muscle functions more effectively to produce the same type of work.

Heavy exercise also increases available ATP, giving muscle extra fuel for a more forceful contraction (Ali 2017). Thus, the plyometric activity done after a muscle group is load-challenged recruits the muscle more entirely and therefore profits from additional energy, resulting in an immediate improvement in functioning. Theoretically, when this happens repeatedly, the improvement becomes a chronic adaptation that delivers more power during sport.

PAP following heavy exercise is maximized when resistance is around 85% of the 1-repetition maximum (Freitas et al. 2017). For prime PAP, muscle requires a rest period between complex exercise pairs, known as the intracomplex rest interval (ICRI). Freitas and colleagues suggest an ICRI of 5 minutes, although some protocols use other time intervals. PAP develops best after multiple sets of heavy movement.

Athletes who respond best to CT start the program with a good strength foundation. Therefore, the best candidate for making gains with a CT regimen is a veteran athlete. Athletes who are currently in competition season also benefit because they can improve their power performance. CT solves the problem of limited time due to practice and performance schedules.

See also: 5 Common Athletic-Performance Supplements: What’s the Evidence?

Complex Training Research

The meta-analysis by Freitas et al. examined the effectiveness of adding a CT program for team sports athletes versus continuing with regular training. The evaluation found that CT improved sprint times and vertical jump heights compared with usual sports training. The most effective CT programs in the review lasted longer than 6 weeks, applied resistance below 85% of 1-RM, and used an ICRI of 2 minutes or more. Of the nine studies included in this review, none found that CT had an adverse or detrimental effect on performance. Interestingly, the reviewers learned that programs which implemented CT fewer than three times per week yielded considerable improvement in sprint times compared with those that included CT three or more times per week.

A similar review from Bauer et al. (2019) examined studies of individual athletes who participated in a CT program lasting at least 4 weeks. These studies compared results in a CT group with those in a control group or an alternative training group. The review of 33 studies found that CT improved 1-RM squat, jump height and sprint time. It also confirmed that CT maximized training time by enhancing performance with minimal investment. The authors found that athletes showed gains despite completing fewer exercises less frequently, and for shorter periods, than the control/alternative training groups. Again, while some benefits were minimal, all were positive.

FROM SCIENCE TO PRACTICE

Research shows that CT is an effective way to improve power in athletes who already have a good strength foundation (Bauer et al. 2019). While there’s no absolute target strength measure, CT is not for the beginner. A CT program is the best way for the athlete who needs to develop power to get a well-rounded workout. To be most effective, trainers should understand the needs of the specific sport when designing the program. A tennis player who wants to serve more aces will perform different exercises than a sprinter.

Developing a CT program is fairly simple:

- Form a complex pair of exercises by matching a resistance exercise with a plyometric drill that uses the same muscle groups.

- Establish the 1-RM of the conditioning activity, then set the weight of the resistance exercise near 85% of the 1-RM mark.

- Have the athlete perform 5–10 reps per set.

- After a period of rest, execute 3 sets of the plyometric activity.

Note:

- The recommended length of the rest period between the two types of exercise is somewhat variable. Studies use ICRIs of 2–10 minutes. The average amount of rest that maximizes PAP and yet allows for an efficient workout schedule seems to be 4 minutes (Bauer et al. 2019).

- A CT training program should last at least 6 weeks. This length of time makes it the perfect early- to midseason regimen. Final competitions begin just as athletes finish the program and make maximal gains.

With all the stated benefits, why did CT fall out of favor? Most likely because improvements produced by a CT schedule may not be as pronounced as those derived from other strategies. Indeed, implementing a separate strength and speed program shows enhancements that often edge out CT workout results. However, studies show that CT program participants make consistent improvements in both strength and speed (Bauer et al. 2018).

Power Up!

Today’s world of sports participation is significantly different from that of the mid-1970s. Athletes at the high school and collegiate levels often train in their sport twice per day, leaving little time for the weight room. When a power workout is well-defined and efficient and fits into the training schedule, athletes are more likely to comply with the sessions and less apt to overtrain. Therefore, for experienced but time-challenged modern athletes, CT may prove to be the retro approach that brings new life to their performance.

Translating Power & Demonstrating Strength Quickly

Athletes need power to be able to sprint for a touchdown or slam-dunk a basketball. Even though athletes generally develop power in the gym, not on the practice field, trainers rarely get enough time with them to work on power components. Look at the equation for power; it helps explain why competitors need time in the weight room in addition to sport-specific training. Power is the result of work over time:

Power = Work / Time

Another way to think about work is as a force multiplied by the distance it moves. Breaking it down this way, the power equation becomes force times displacement, divided by time:

Power = (Force x Displacement) / Time

Since displacement divided by time is also known as velocity, you can further modify the power equation to look like this:

Power = Force x Velocity

Therefore, when considering an athlete, think of strength as the force and speed as the velocity. Powerful athletes are both strong and fast. More importantly, they can demonstrate strength quickly, like a lineman jumping off the line to hold a block, a batter smashing a baseball over the fence or a long jumper on the approach.

Source: Holzner 2011.

See also: Peak Neuromuscular Power for Your Athlete Clients

Complex Training Pairs: Lower Body

The following complex training workout example is an overall total-body program for general use and guidance. When training a specific athlete, consider the demands of the sport and design the program accordingly.

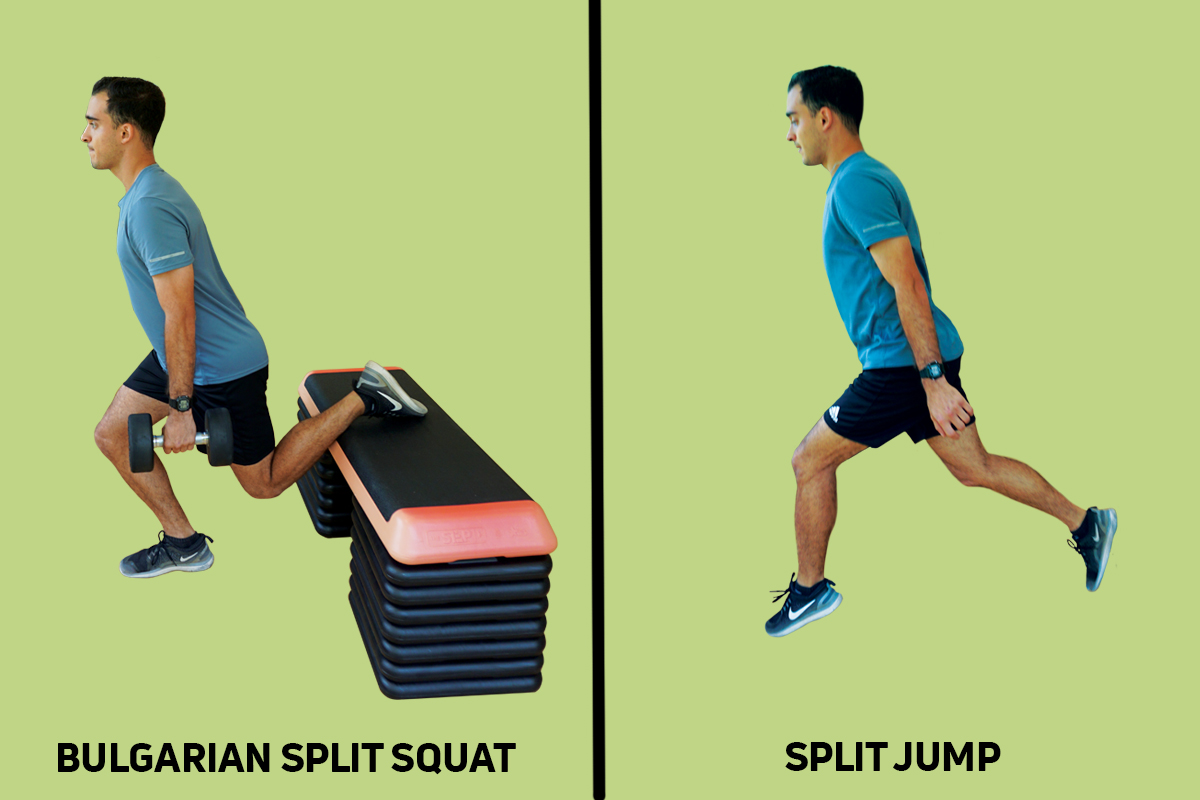

BULGARIAN SPLIT SQUAT + SPLIT JUMP

This CT pair trains gluteals, quadriceps, hamstrings and calf muscles.

- Perform 3 sets of 6- to 8-RM Bulgarian split squats (5–8 each leg).

- Rest for 4 minutes. Do 3 sets of 6–12 reps of plyometric split jumps (each leg, alternating).

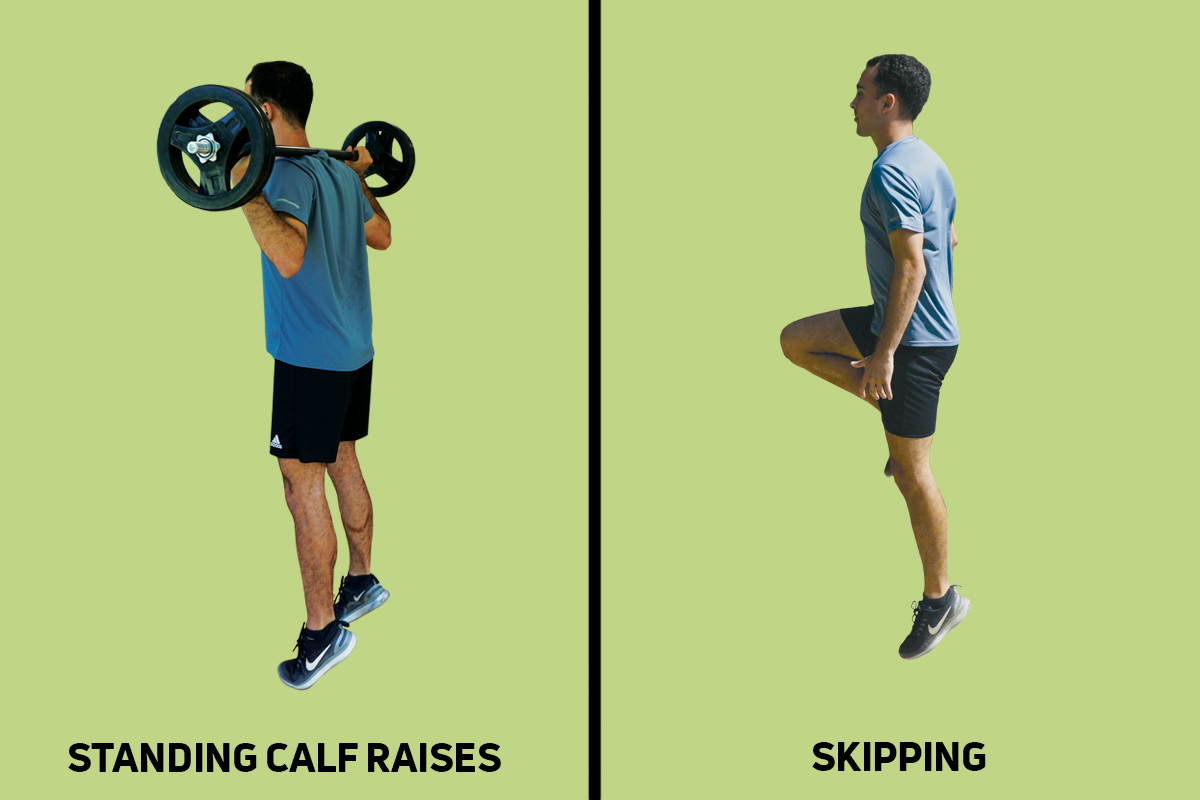

STANDING CALF RAISE + SKIPPING

This CT pair trains the gastrocnemius, soleus and other lower-leg muscles.

- Perform 3 sets of 6- to 8-RM standing calf raises (5–8 each leg).

- Rest for 4 minutes.

- Do 3 sets of skipping for 5 meters (about 16 feet).

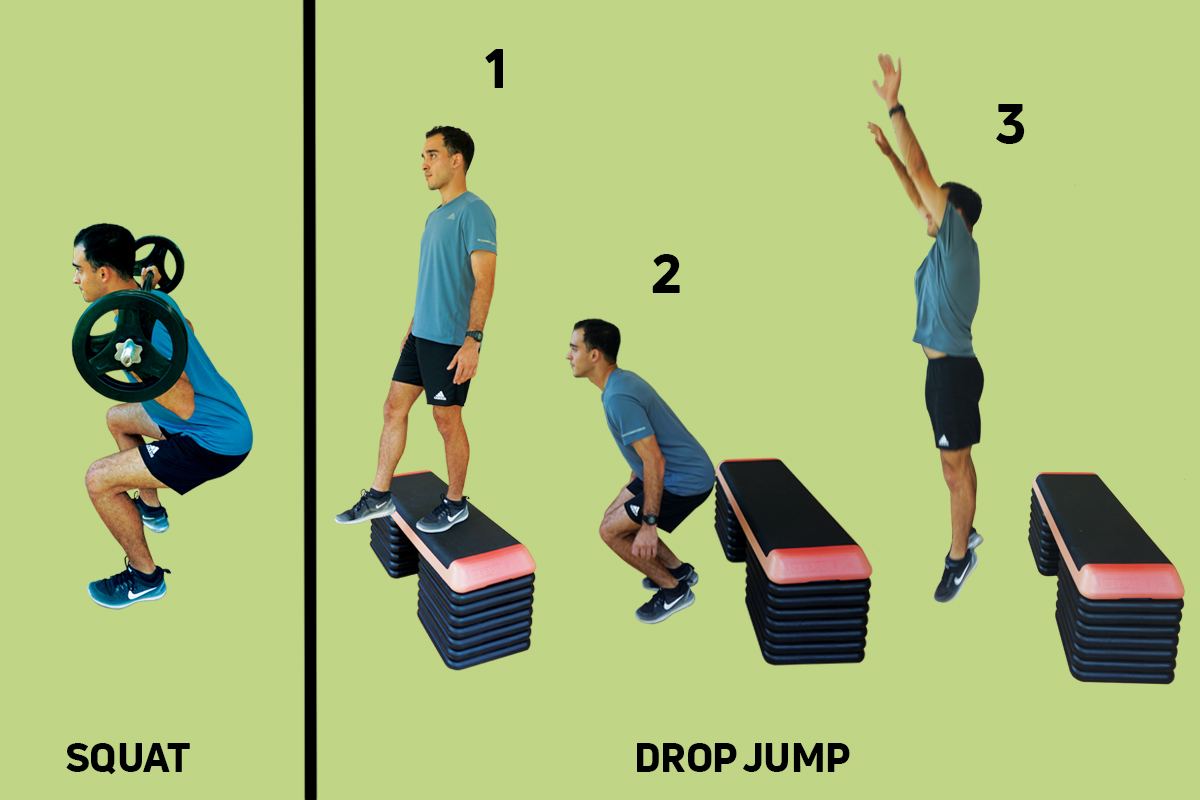

SQUAT + DROP JUMP

This CT pair trains the gluteals, quadriceps, hamstrings, calf and core muscles.

- Perform 3 sets of 6- to 8-RM squats (5–8).

- Rest for 4 minutes. Do 3 sets of 6–12 drop jumps.

Complex Training Pairs: Upper Body

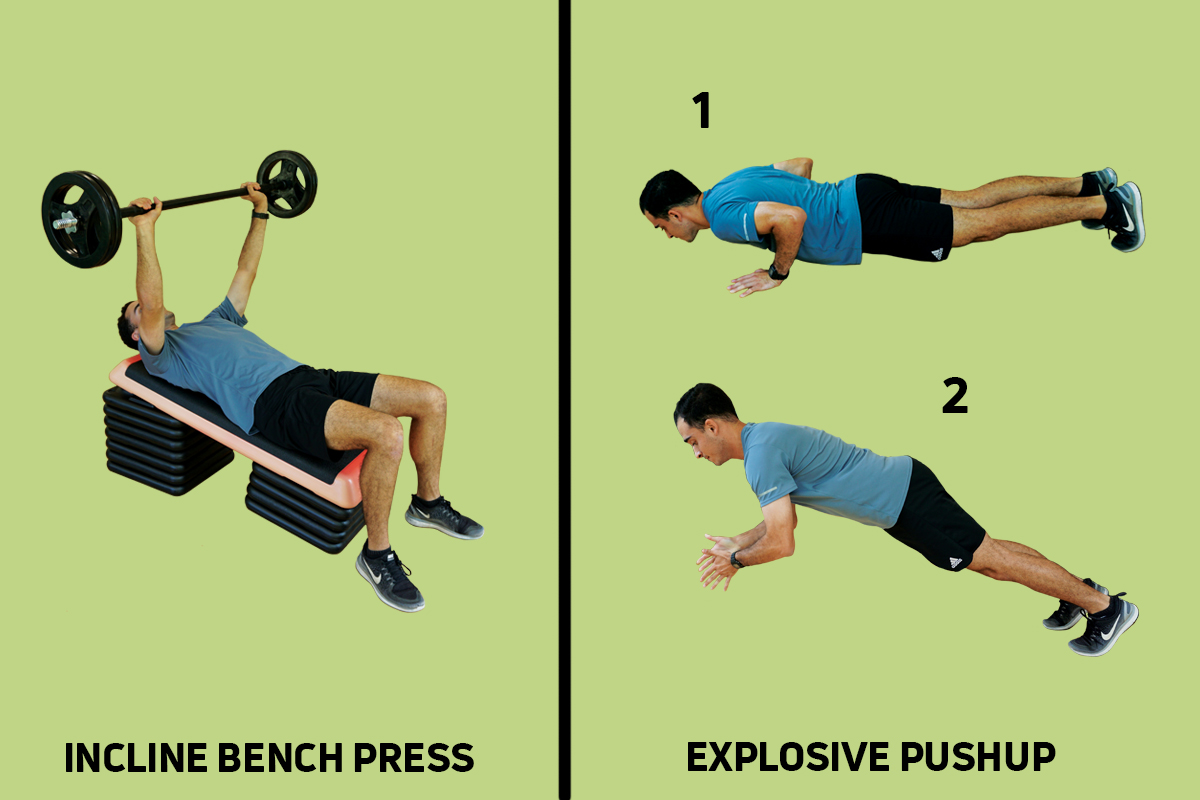

INCLINE BENCH PRESS + EXPLOSIVE PUSHUP

This CT pair works the pectoralis, deltoid, triceps and core muscles.

- Perform 3 sets of 6- to 8-RM incline bench presses (5–8).

- Rest for 4 minutes. Perform 3 sets of 6–12 explosive pushups (clap optional).

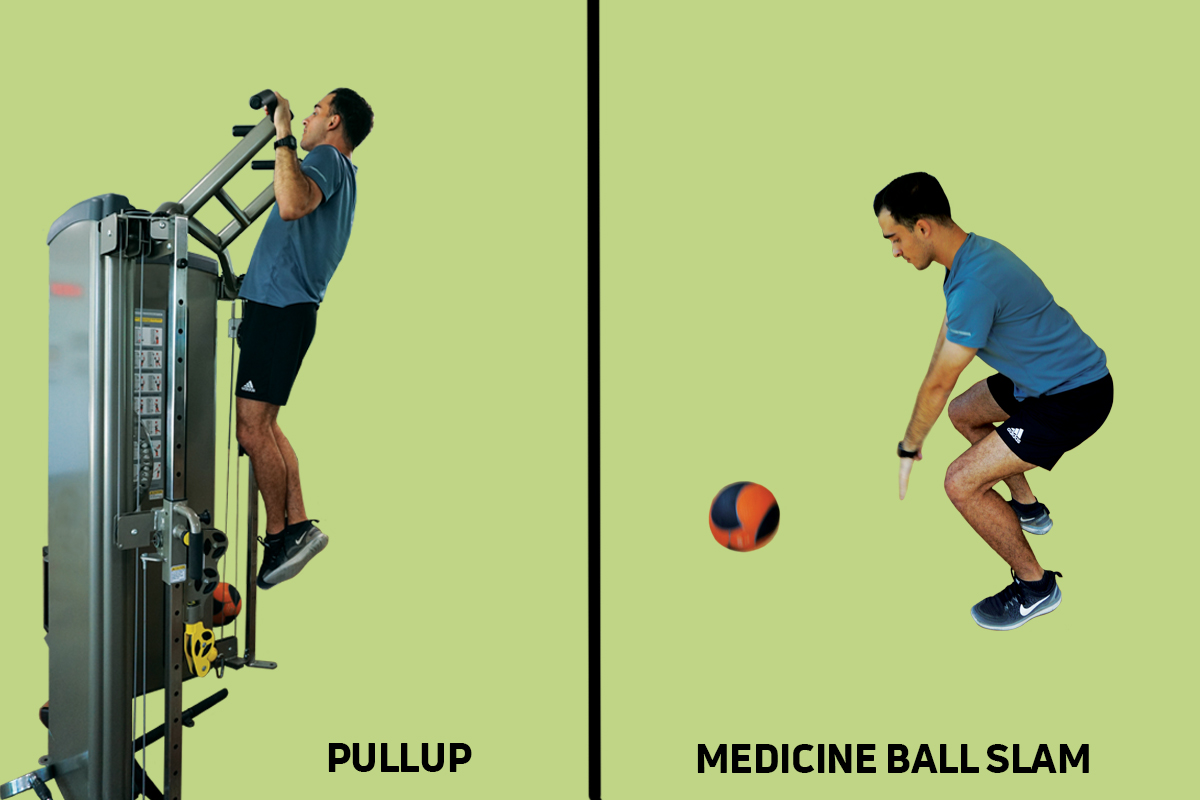

PULLUP + MEDICINE BALL SLAM

This CT pair works the lats, biceps, forearms, trapezius and upper-back muscles.

- Perform 3 sets of 6- to 8-RM pullups (5–8), adjusting with assisted strap or adding weights as needed.

- Rest for 4 minutes.

- Perform 3 sets of 10–15 medicine ball slams, using a ball that is 5%–10% of body weight.

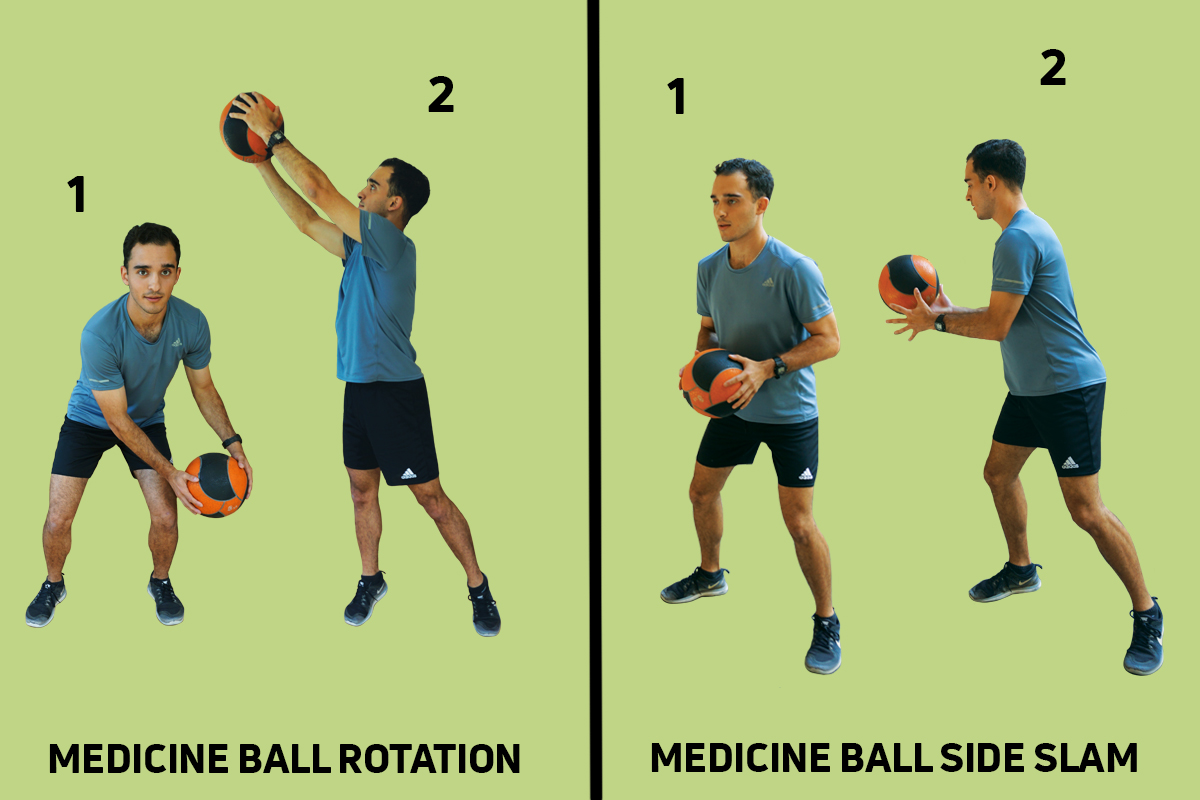

MEDICINE BALL ROTATION LIFT + MEDICINE BALL SIDE SLAM

This CT pair works the core and lower-body stabilizing muscles, as well as the shoulder, chest and arm muscles.

- Perform 3 sets of medicine ball rotation lifts using a ball that is about 10% of body weight (6–10 each side).

- Rest for 4 minutes.

- Perform 3 sets of side medicine ball slams using a ball that is about 5% of body weight (6–10 each side).

See also: Training Techniques for High-Performance Older Athletes

Sample Program

Below is a sample total-body complex training workout. For maximal results, use resistance near 85% of 1-RM for the heavy conditioning activity. Perform this workout twice per week in addition to doing regular sport practice sessions. Continue the program for 6–8 weeks, adjusting the resistance as strength improves.

References

Ali, K., et al. 2017. Complex training: An update. Journal of Athletic Enhancement, 6 (3), 1–5.Bauer, P., et al. 2019. Combining higher-load and lower-load resistance training exercises: A systematic review and meta-analysis of findings from complex train