Motivational Interviewing: Talking Their Way to Health

Motivational interviewing can drive sustainable behavior change. Here's how to make it happen.

Do you want to be a wrestler or a dancer?

This question stands at the center of motivational interviewing (MI), which emerged more than three decades ago to assist people in making difficult changes like overcoming addiction. Health coaches can use MI to help people stop harmful behaviors and start helpful ones. Consider a likely scenario:

A new client has prediabetes and needs your help. Her doctor says she needs to lose 5% of her body weight and exercise 150 minutes per week—the standard advice for preventing type 2 diabetes. While she doesn’t want to get diabetes, she hates exercise and has never succeeded at losing weight and keeping it off. She has little confidence that this time will be any different.

As her health coach, you might try

A: explaining the reasons why she should exercise and eat a healthy diet and giving her a plan showing her what to do

or

B: exploring her concerns about developing diabetes and figuring out why she wants to be healthy

These options use contrasting communication styles that have a profound impact on people’s receptiveness to change. Option A is a “directing” communication style—gathering information, determining what’s wrong and telling the client how to fix the problem. It’s like wrestling because the client often strikes a defensive pose. Option B is a “guiding” communication style—helping the client explore reasons to change. This is like dancing because the two of you cooperate to reach a common goal.

The co-founders of motivational interviewing say dancing is the better way to use talk to encourage behavior change: “A good MI conversation looks as smooth as a ballroom waltz. Someone is still leading in the dance . . . without tripping or stepping on toes” (Miller & Rollnick 2013).

Learning MI: The Fundamentals

MI skills are most critical—and effective—with ambivalent clients.

With motivational interviewing, you’re helping clients talk themselves into changing for the better. MI evolved in response to behavior change strategies that focused on either telling people what to do or letting them call their own shots with little direct guidance. Both of these approaches tend to suffer from poor follow-through from the person trying to change.

MI skills are most critical—and effective—with ambivalent clients, those who are not quite certain they need to change but who acknowledge the benefits and downsides of moving in a new direction.

The effectiveness of motivational interviewing has been extensively studied and evaluated. More than 25,000 scientific papers and 200 randomized controlled trials have been published since MI was first described in the treatment of alcohol addiction in the 1980s (Miller & Rollnick 2013). A recent review of more than 130 review articles and meta-analyses from 2000 to 2018 evaluated MI’s role in stopping or preventing unhealthy behaviors (substance use, gambling), promoting healthful behaviors (oral health, nutrition, exercise, weight management, medication adherence) and addressing multiple health-related problems (excess drinking, smoking, physical inactivity). Note that, for all this research, the reviewers concluded that the quality of the evidence was limited and more high-quality research is needed (Frost et al. 2018).

See also: The Secrets to Behavior Change: Principles and Practice

The Spirit of MI

While motivational interviewing methodologies have been refined over time, the original spirit remains unchanged: “MI involves a collaborative partnership with clients, a respectful evoking of their own motivation and wisdom, and a radical acceptance recognizing that ultimately whether change happens is each person’s own choice, an autonomy that cannot be taken away no matter how much one might wish to at times” (Miller & Rollnick 2013).

THE FOUR PILLARS

Client-coach conversations in MI have four requirements:

Collaboration. The client and coach are partners. As Miller & Rollnick put it: “Without partnership, there is no dance.”

Acceptance. An MI-centric coach demonstrates “unconditional positive regard” for the client, rooted in respect, trust and empathy.

Compassion. Motivational interviewing benefits the client—not the coach.

Evocation. Clients are the experts on themselves. The coach’s role is to “call forth . . . strength and wisdom from the client” (Miller & Rollnick 2013).

THE FOUR PROCESSES

Motivational interviewing goes through four phases:

- Engaging. The coach and client build rapport and trust.

- Focusing. The coach and client develop a shared agenda for coaching sessions.

- Evoking. This is the heart of motivational interviewing. Coaches help clients explore their motivation to change and resolve their ambivalence about it. Much of MI’s power lies in the art and science of evoking.

- Planning. Finally, the client resolves to change and is ready to develop and implement an action plan. Here, the client is “thinking and talking more about when and how to change and less about whether and why” (Miller & Rollnick 2013).

Key Skills: OARS

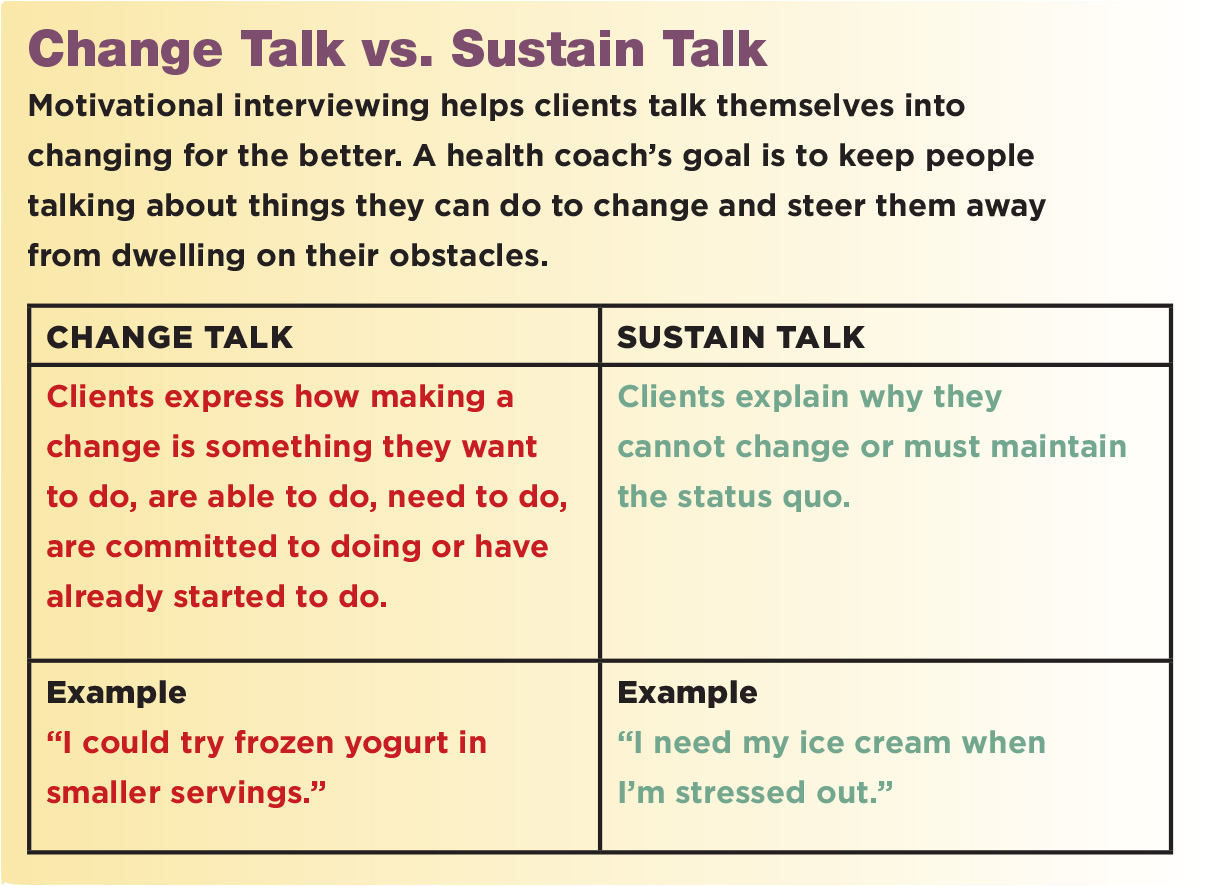

Motivational interviewing helps people reorient how they think—and feel—about change. An MI interview guides a client toward “change talk”—statements by the client (not the coach!) arguing why he or she needs to change.

Trying to convince someone to change will often make an unwanted behavior more likely to stick. By contrast, when people talk themselves into changing, they are much more likely to turn intention into action. As Miller & Rollnick say, “If you are arguing for change and the client is arguing against it, you’ve got it exactly backward.”

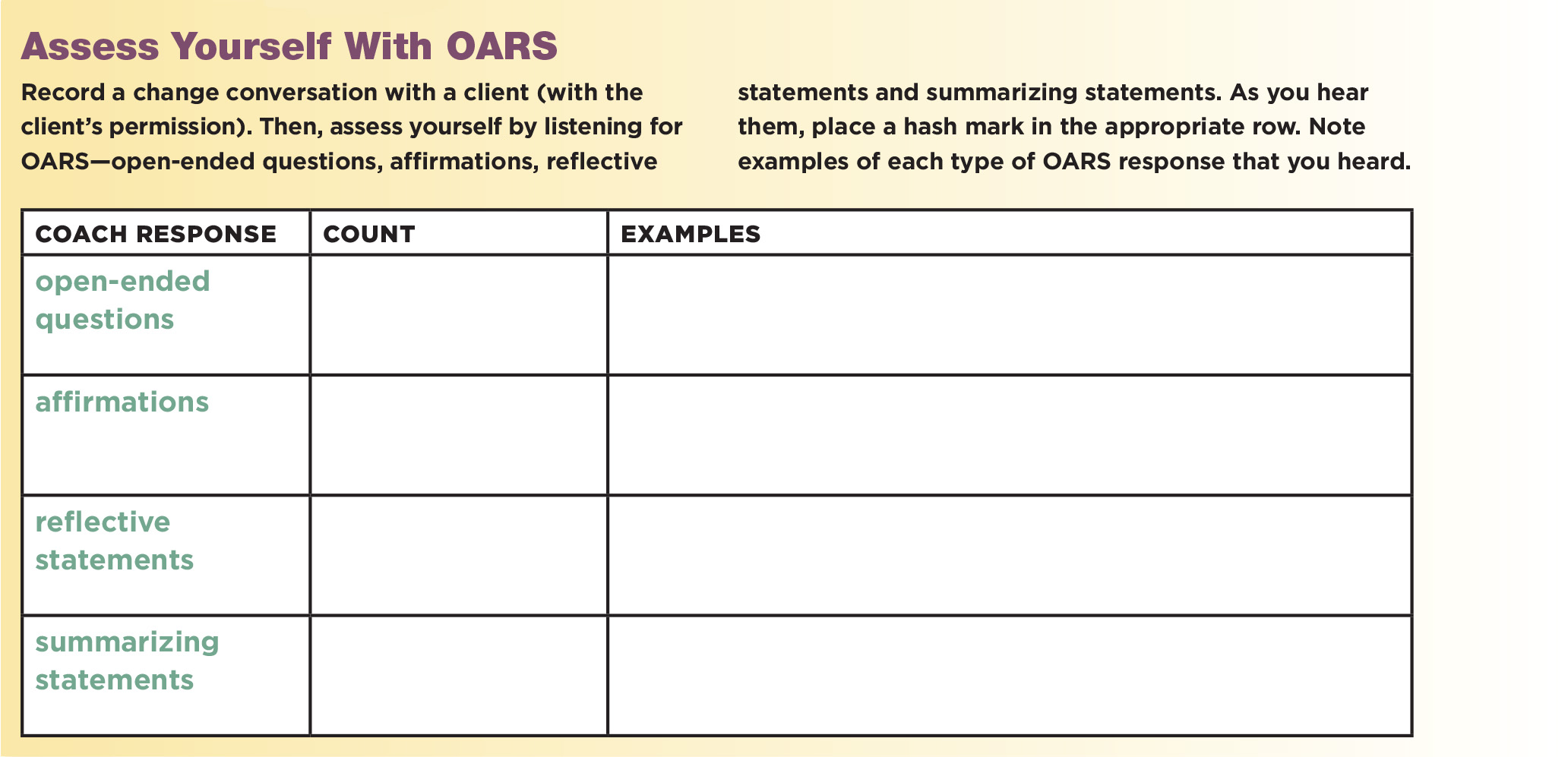

To evoke change talk, MI uses four communication techniques, summed up in the mnemonic OARS.

OPEN-ENDED QUESTIONS

These questions cannot be answered with a simple yes or no. Open-ended questions often start with “how,” “what,” “why” or “what if.” For instance, instead of asking, “Do you like fruits and vegetables?” an open-ended question asks, “What healthy foods do you enjoy the most?”

AFFIRMATIONS

These acknowledge a client’s strengths, abilities and positive behaviors, focusing more on what’s going right than what’s going “wrong.” Affirmations help a client build confidence and self-efficacy for change. For example, a statement such as “You went for a walk even though you didn’t feel like it at first” is much more likely to produce continued positive change than a remark like “Your walk was only 5 minutes instead of the 30 you had planned.”

REFLECTIVE STATEMENTS

These are best guesses that try to identify the meaning or intention that underlies a client’s statement. Coaches are trying to help clients think more deeply about how they feel and what motivates their actions. It is okay if a coach’s best guess is not accurate as long as the question comes from a genuine desire to better understand and collaborate with the client. If the reflective statement misses the boat, then the client will usually correct the coach and likely elaborate further.

Reflective statements help a client work through ambivalence and build the confidence and commitment to make a change. For example, if a client says, “I don’t have time to exercise,” the coach could respond, “You would be more active if you could free up a few more minutes in your day.” Mastering reflective statements is essential to building fluency in motivational interviewing.

SUMMARIZING STATEMENTS

Here, coaches recap their understanding of what a client has said or pull together the client’s thoughts. Summarizing statements often come at the end of a coaching session. They help ensure that coach and client are on the same page, while also setting a direction for next steps.

See also: Health at Every Size: A Sound Approach to Behavior Change

10 Motivational Interviewing Strategies

Practice strategies to develop your skill of motivational interviewing.

Motivational interviewing is a skill you have to develop over time with patience and practice. Adopting these 10 strategies will improve your MI skills. To get started, choose a strategy, practice it to near-mastery and then add another one.

1. TALK LESS

Talking less is essential to successful motivational interviewing. Your goal is to build a partnership by allowing clients to do most of the talking. Prompt a client with open-ended questions, such as, “What brings you here today?” Avoid thinking about what to do next. Just focus on listening to the client’s words. Ideally, a client will do 50% or more of the talking in a coaching visit.

2. LISTEN FOR AMBIVALENCE ABOUT CHANGE

A client who says “I am here because my doctor told me I need to see you to lose weight” may be ambivalent about change. The client shows some readiness to change but may be seeing you only to follow through on a doctor’s orders. MI is ideal for ambivalent clients because it helps them move from considering change to getting ready to change.

3. HEAR (AND EVOKE) CHANGE TALK

The secret sauce of motivational interviewing is responding effectively to change talk (in which the client states the benefits of changing a health behavior).

Generally, change talk consists of “desire, ability, reasons and need” statements (DARN for short). Examples:

- Desire. “I want to be able to run a 5K with my daughter.”

- Ability. “I know I could eat more fruits and vegetables if I really put my mind to it.”

- Reasons. “If I avoid getting diabetes, I know my quality of life will be so much better.”

- Need. “I need to be more active, but I’m just not sure how to fit activity into my day.”

Speaking in reflections (see step 5) is the most impactful way to respond to change talk.

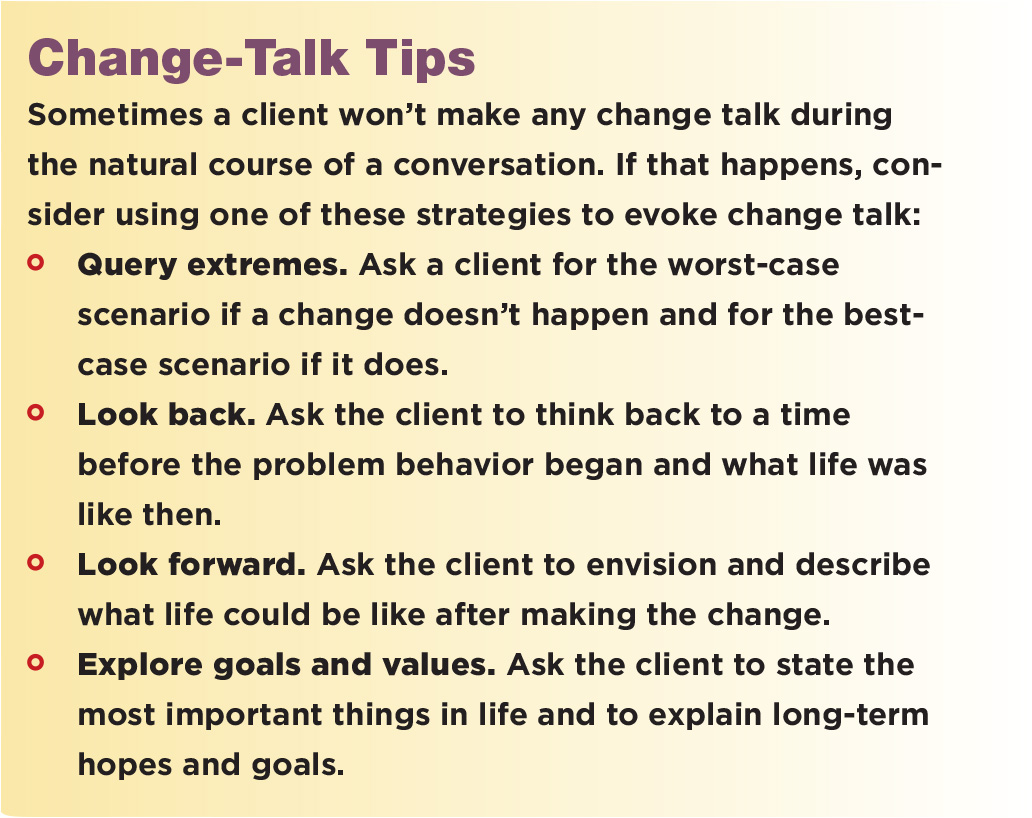

4. ADDRESS SUSTAIN TALK–BUT DON’T DWELL ON IT

Sustain talk happens when a client describes barriers, challenges or reasons why a change is not feasible. You want to reframe and downplay these statements without prompting more sustain talk, since the latter would help a client move away from making a change. To break a cycle of sustain talk and get back to evoking change talk, try the strategies below:

- Emphasize autonomy. Acknowledge that it is up to the client to change. You might say, “Only you can control whether or not you make a change.”

- Reframe. Offer a different perspective on a client’s statement. If a client says, “I have tried and failed at losing weight so many times; I don’t think I can do it this time, either,” you might say, “You have been persistent in trying to find the strategy that will work for you. Losing weight must be very important to you.”

- Agree—with a twist. Start with a reflective statement to agree with the client, then follow with a reframing statement. For example, if a client says, “I don’t have time to cook healthy meals,” you can say, “Cooking healthy meals takes time. You have other ways to spend your time that are of higher priority.”

- Get a running head start. Prompt a client to provide reasons not to change followed by reasons to change. This is much like listing pros and cons, but starting with cons. Use this strategy only when a client has expressed little to no change talk. Otherwise, listing reasons not to change can reinforce the status quo.

- Come alongside. When a client offers little to no change talk and an abundance of sustain talk, you can say, “Perhaps, for now, it is better to stay as you are.” A comment like this often prompts a client to respond with change talk (e.g., “Oh no, I am not perfect; I can probably do something to improve”). Sometimes a client has no intention of changing. In these cases, coming alongside the client in this way can let you preserve the relationship without spending a lot of time and energy trying to help someone who doesn’t want help.

5. SPEAK IN REFLECTIONS

Avoid asking a lot of questions or providing a lot of advice and instruction. Instead, respond primarily in reflections—repeating back what you heard the client say, including a best guess at the statement’s meaning. Try to reflect more change talk than sustain talk. Reflection can take several forms:

- Simple reflection. Simply repeat or restate what a client says. For example, if a client says, “I want to lose weight,” a simple reflection would be “Losing weight is important to you.”

- Complex reflection. Say something that aims to get at the client’s underlying meaning or feeling. For example, if a client says, “I love desserts, but I definitely don’t want to get diabetes,” a complex reflection would be, “You are afraid that if you keep eating the way you are eating, you are going to get diabetes.”

- Straight reflection. Provide a simple or complex reflection in response to a client’s sustain talk. For example, if a client says, “I already exercise and eat a healthy diet, but I can’t ever lose any weight,” a straight reflection might be, “You already have very healthy habits, so it is not worthwhile to make any changes to try to lose weight.” Often, change talk follows a straight reflection.

- Amplified reflection. Respond to sustain talk with an overstatement. Deliver it with empathy and no sign of sarcasm or impatience, which could prompt a defensive or hostile reaction. For example, when a client says, “I am only here because my wife made me come,” an amplified reflection might be, “Your wife is worrying needlessly about your health.”

- Double-sided reflection. Combine two reflections—one on a client’s sustain talk, followed by another on a client’s change talk. For example, “You don’t have time to cook, and, when you do cook, you feel better and save money.”

While you are learning the language of motivational interviewing, many of your statements will be simple reflections. With practice, it can become easier to use complex reflections that help to further prompt behavior change.

6. USE THE CONFIDENCE RULER TO PREPARE FOR PLANNING

Coaches talk a lot with clients about planning and setting goals. While this may work well with committed clients, it can be counterproductive for clients ambivalent about change.

The confidence ruler is great for ambivalent clients because it helps them express reasons for change and identify their best next steps to start planning for change. It works like this:

- Ask a client, “On a scale from 1 to 10, how confident are you that you could make this change if you decided to?”

- Ask, “How come you are [x] and not [x-2]?” (Example: If a client answers 5, ask why she didn’t say 3.) This question almost always elicits change talk because it reveals how the client’s confidence exceeds his doubts. On the other hand, asking “Why are you a 3 and not a 5?” usually triggers sustain talk by revealing more doubt than confidence.

- Respond with a reflective statement. Now ask, “What would it take to get from [x] to [x+2]?” This process helps the client start to identify a change plan.

7. RESIST THE RIGHTING REFLEX

Miller & Rollnick say the “righting reflex” is the powerful tendency among health professionals to give advice, push recommendations and offer solutions. Unfortunately, your eagerness to promote change is counterproductive if the client is ambivalent about it. Often, an ambivalent client instinctively reacts to advice by defending the status quo, reducing the likelihood of sustained behavioral change.

If you feel tempted to advise or recommend actions to an ambivalent client, pause and make a reflective statement that could prompt the client to come up with a solution. For example, if a client skips lunch at work because she is too busy, don’t jump into a discussion of finding time to eat (bringing her own lunch, forcing herself to take a break, etc.). Instead, offer a reflection: “If you were a little less busy at work, there would be time to eat a healthy lunch.” The client might respond with something like, “Yes, if only I had just a little bit more time.”

Then you can offer a statement more likely to get the client to find her own solution (and, thus, be more likely to implement it). For example: “I wonder if there might be a way to free up some time.” From here, the client might offer ideas of ways to free up time.

8. POUNCE ON CAT STATEMENTS

When a client starts making CAT statements—which refer to commitment, activation and taking steps—it’s time to recognize that the client has worked through his ambivalence and is likely ready to begin planning for change.

As you work with clients, listen for

- commitment statements—versions of “I will change”;

- activation statements, including “I am ready to” or “I am prepared to” change; and

- statements about taking steps, indicating that the client has already begun to make a change.

Also called “mobilizing change talk,” CAT statements can be crucial precursors to sustainable behavior shifts.

9. INFORM AND ADVISE WITH PERMISSION

Sometimes it makes sense to offer a client health education or advice. For example, once a client is ready to begin planning, you may get questions about meal plans or exercise programs. Offer information and advice only if a client specifically asks for it or after you’ve explicitly asked for permission and the client has granted it. Make sure your clients recognize that they are free to agree or disagree and that the information should be used in the context of their plans for change. Finally, in providing advice, offer a menu of choices rather than one “best” plan.

10. ELICIT–PROVIDE–ELICIT

When educating and advising, follow the elicit–provide–elicit sequence:

- Elicit. Ask for permission to provide information, and then ask a few open-ended questions to understand what the client already knows on the topic.

- Provide. Give information of most relevance to the client in small doses.

- Elicit. Check back with the client to assess her understanding and response to the information.

See also: Behavior Change: What the Research Tells Us

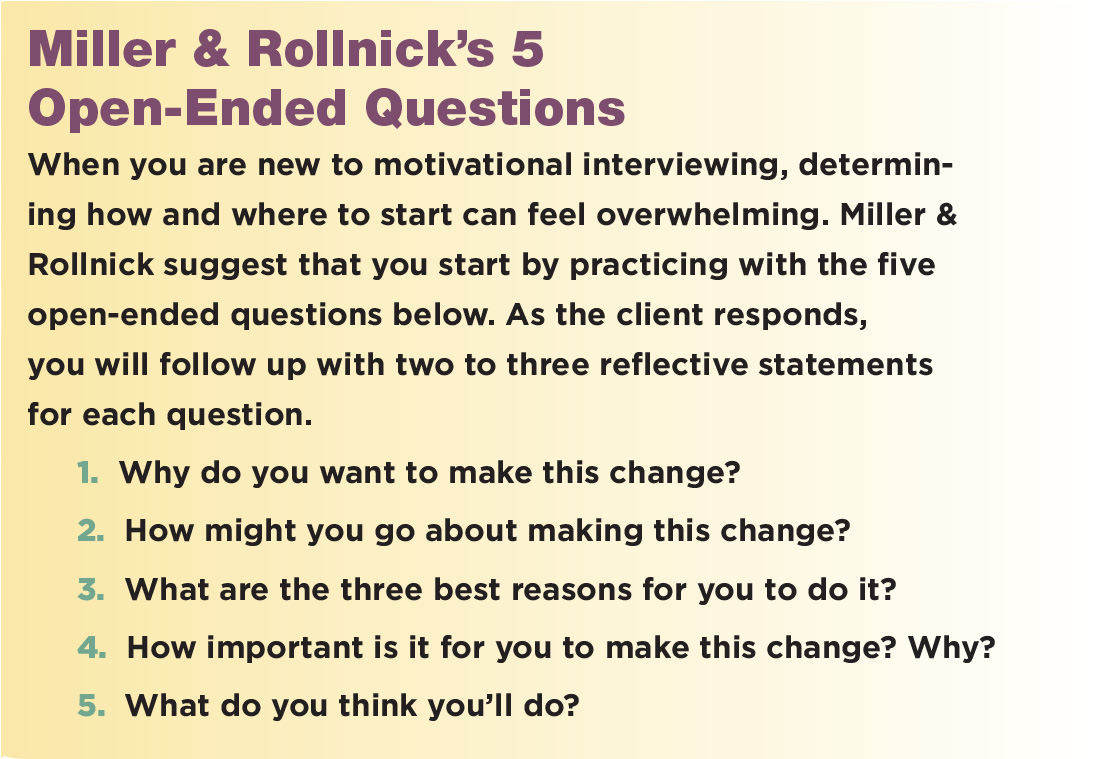

Stop Wrestling, Start Dancing

Now that you know the fundamental principles and strategies of motivational interviewing, practice pulling it together with “Miller & Rollnick’s 5 Open-Ended Questions” (above). The best way to improve at motivational interviewing is to get a lot of practice and feedback. Check your mastery of OARS by recording a coaching session (with the client’s permission) and tallying your responses by using the “Assess Yourself With OARS” tool, below.

Mastering motivational interviewing is like learning to dance. It takes time, practice and many mistakes to develop proficiency and grace, but the payoff is a solid return on investment for any health coach.

References

Frost, H., et al. 2018. Effectiveness of motivational interviewing on adult behaviour change in health and social care settings: A systematic review of reviews. PLOS ONE, 13 (10), e0204890.

Miller, W.R., & Rollnick, S. 2013. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change, 3rd ed. New York: Guilford Press.

Natalie Digate Muth, MD, MPH, RD

"Natalie Digate Muth, MD, MPH, RDN, FAAP, is a board-certified pediatrician and obesity medicine physician, registered dietitian and health coach. She practices general pediatrics with a focus on healthy family routines, nutrition, physical activity and behavior change in North County, San Diego. She also serves as the senior advisor for healthcare solutions at the American Council on Exercise. Natalie is the author of five books and is committed to helping every child and family thrive. She is a strong advocate for systems and communities that support prevention and wellness across the lifespan, beginning at 9 months of age."