Core Stability for Enhanced Daily Function

%{Video}%

It’s early morning, and you arrive at the gym to discover a voice message from your 8:00 am client, Mary. She has called to let you know she will be unable to make her appointment because she has strained her back and is laid up in bed—for the third time this month. A consummate professional, you call to follow up with her. Mary explains that she “did something” to her back as she was rushing to get the kids off to the school bus. You wish her well, hang up the phone and contemplate her injury.

Aware that she is prone to back problems, you consistently lead her through a thoughtful warm-up that includes core activation exercises and dynamic movements. But even with a quality warm-up, it seems as though she cannot reach her potential, owing to continual stiffness or aches in her body. Mary is your typical three-times-per-week fat loss and health improvement client.

Aches and pains are a too-common occurrence among the general population. Static, seated desk work, faulty biomechanics and inactive core musculature are all thought to contribute to this growing problem. Not only does it inhibit quality of life in those affected, but it also negatively impacts your business. When Mary does not cancel her sessions because of back pain, chances are you must spend the first 10–15 minutes of your session working through core stability and mobility exercises. While important, this may not be the best use of your time, as Mary could be doing these exercises every day on her own and seeing a synergistic effect.

Instead of tending to Mary’s inadequate core strength at the beginning of her sessions, teach her a simple, yet effective daily morning core routine that will help her develop greater neural motor control; improve core stability; and eliminate or reduce aches and pains. Core stability relies on endurance and awareness, making daily practice essential for progress and improved motor learning.

One of the most important components of any exercise program is core strength. Known as the “powerhouse,” the core is the foundation—or center—of the functional kinetic chain (Akuthota & Nadler 2004). Similar to the foundation of a house, the core supports and stabilizes the spine during static positions and movement. According to Kibler, Press & Sciascia, “‘core stability’ is defined as the ability to control the position and motion of the trunk over the pelvis to allow optimal production, transfer and control of force and motion to the terminal segment in integrated athletic activities.”

In day-to-day terms, core stability is necessary for efficient and injury-free movement patterns. But considering the current prevalence of back pain cases alone—the Mayo Clinic (2009) states that “four out of five people in the United States will experience low back pain at least once during their lives”—core stability appears to be lacking among the general population. This is hardly surprising, as many people sit for a vast majority of the day, relying for support on back rests and computer desks instead of the core. Muscles grow tight and inefficient as a result, limiting range of motion, increasing injury risk and initiating potentially painful movement patterns (Willson 2005). >>

To fully comprehend why core conditioning is required daily, it’s best to understand the structures and mechanisms involved. Researchers and professionals debate what, exactly, makes up the core; for the purposes of this article, we will define the core as comprising the muscles and connective tissue that attach into the lumbopelvic hip complex, thoracic spine and cervical spine (Akuthota & Nadler 2004). When activated properly, these tissues will act as a brace—or girdle—that helps align and maintain stability of the spine, pelvis and shoulder girdle. An active core is thought to reduce premature wear and tear of the body’s structures by optimizing force distribution. A weak core, we can assume, diminishes a person’s ability to reduce, produce and stabilize forces (Peate et al. 2007; Kibler, Press & Sciascia 2006; Akuthota & Nadler 2004).

The core is also made up of both type I and type II muscle fibers, or slow-twitch and fast-twitch fibers, respectively. The type I muscle fibers fire long term and keep the body stabilized. Without these stabilizers, any movement that takes place will be inefficient and may cause premature soft- and hard-tissue degeneration due to excess friction.

Core conditioning continues to increase in popularity. Google the term and you will likely be met with pages upon pages of explanations, exercises and more. Despite such mainstream popularity, more research is required to fully understand the specific mechanisms of the core and its relationship to injury and prevention. However, according to Willson and colleagues (2005), “Core stability may provide several benefits to the musculoskeletal system, from maintaining low back health to preventing knee ligament injury.” Willson adds that “current evidence suggests that decreased core stability may predispose to injury and that appropriate training may reduce injury.”

Several other studies support Willson’s claims. One study of 433 firefighters discovered a link between core stability and a 62% reduction in lost work time due to injury. Core stability was also linked to a 42% decrease in total injury count. Intervention methods included exercises such as “glute bridges” and dead bugs (Peate et al. 2007). Another study of back pain patients found that 90% of those participating in “an aggressive physical rehabilitation program consisting of back school and stabilization exercise training” experienced good or excellent outcomes (Saal 1989). This evidence proves promising and highlights the positive benefits of the development of greater core strength and stability.

Optimally, perform a thorough structural assessment before starting a client on the morning core routine. If the client complains of pain during any of the exercises, stop immediately.

Urge your client to perform the morning core routine every day, just after rising from bed. Completing the program in the morning is ideal for two reasons.

First, this is typically the time in which the body is cold, stiff and most prone to injury. Executing the core routine prior to movement is like doing a preworkout warm-up. It helps to increase soft-tissue blood flow, warmth and pliability; facilitates greater motor control and neurological awareness; permits gradual metabolic adaptation for enhanced cardiorespiratory performance; and helps develop a psychological readiness for upcoming tasks. All of these benefits lead to more efficient movement patterns and injury prevention/reduction.

Second, a morning routine helps to assure daily adherence. Chances are, if your client puts off the program until later, it will be the first thing to be eliminated from a busy schedule.

Very little is needed to complete the routine, making it highly convenient. There are 10 exercises depicted here (see the sidebar “The Exercises”); however, your client needs to choose only six of them. He will complete 2–3 sets of each, working at about 50%–70% of maximum intensity.

These core exercises are designed specifically for improved neuromuscular efficiency, not hypertrophy, so moderate intensity is warranted. The client will not experience significant muscular fatigue; instead the responses should be warmth, improved flexibility and increased awareness of the muscle tissues involved.

The movements of the morning core routine are simple, but they require optimal form for effectiveness. To ensure excellent mechanics, thoroughly describe and demonstrate each of the exercises and ask the client to do the same. Provide the client with written explanations and corresponding images in a handout format that she can refer to at home. At your next meeting, ask the client to demonstrate the exercises again. At this time you can critique form and also determine adherence. Since the routine is to be completed at home, compliance journals, e-mail and text message reminders and feedback may be necessary to ensure regular practice.

When performed daily, the morning core routine can improve neuromuscular control, spinal stability, movement pattern efficiency and injury prevention/reduction. Enhanced core strength and stability are also likely to increase a client’s ability to perform at greater intensities during exercise sessions. This will help the client achieve his goals. n

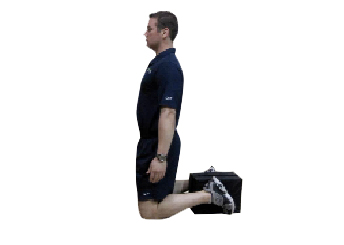

1. TVA (transversus

abdominis) Draw-Ins From Quadruped Position

From quadruped position, inhale deeply and then exhale. As you exhale, draw bellybutton toward spine and up into chest. Hold this position for minimum of 6–20

seconds. Perform 3–5 reps per set. Take 1–2 recovery breaths

between reps, if needed.

2. Prone Pillow Squeezes

In prone position, dorsiflex feet and flex knees to 90 degrees while keeping feet and legs hip to shoulder width apart. Place pillow, foam roller, yoga block or other similar tool evenly between feet and ankles. As you squeeze pillow, engage glutes to achieve hip extension. Hold each contraction for 1–2 seconds (50%–70% intensity).

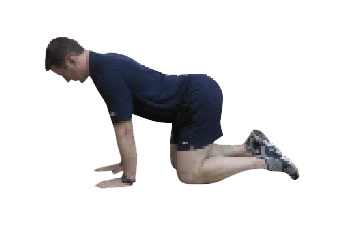

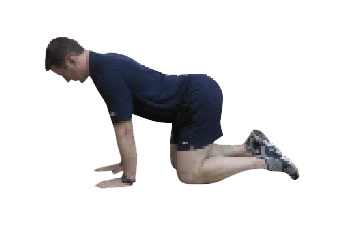

3. Quadruped

Pillow Squeezes

From quadruped position, let belly become heavy, and allow lumbar spine to sink into lordosis. Place pillow between feet

and ankles. Squeeze pillow, holding each contraction for

1–2 seconds (50%–70% intensity).

4. Kneeling Pillow Squeezes

From kneeling position, assume neutral spine. Place pillow between feet and ankles. Squeeze pillow while

simultaneously contracting glutes (50%–70% intensity).

5. Prone Presses

Assume prone position on floor, dorsiflex feet and ankles and posteriorly tilt pelvis if necessary to achieve neutral spine. Place arms in 90–90 position with hands and wrists slightly higher than elbows. Perform shoulder press so that both hands come together above head. Keep hands and wrists slightly elevated above elbows.

6. Modified Cobra

Assume prone position on floor. Dorsiflex feet and ankles, and posteriorly tilt pelvis if necessary to achieve neutral spine. Begin with arms extended above head and touching (palms down). Slowly bring arms toward knees. As arms pass by shoulders, lift head,

neck and torso while keeping navel drawn in. Hold

at top of movement with shoulder blades retracted and depressed.

7. Glute Bridge

In supine position, create 90-degree angle at knees with feet on floor. While maintaining neutral spine, engage glutes so that hips move into hip extension.

8. Quadruped Opposite Arm/Leg Raise

(Bird-Dog)

From quadruped position, brace abdominals and extend contralateral arm and leg. Maintain original hand and knee placement, and keep hips level throughout exercise. Head and

neck should remain neutral.

9. Plank

From prone position, dorsiflex feet and ankles, engage glutes and brace abdominals. This will create tension throughout posterior chain. Place elbows directly under shoulders, and direct hands

toward head to form triangle with arms. Avoid squeezing fists, to optimize blood flow through fingertips.

10. Side Plank

Begin by lying on right side of body with feet stacked. Place right

elbow just below right shoulder and lift hips, ensuring that elbow and shoulder are

in line, creating 90-degree angle. Repeat on other side.

@VIDEO_FILE:/files/video/201001video02.mp4:320:240@