Cardiovascular Exercise Improves Memory

Roig, M., et al. 2013 The effects of cardiovascular exercise on human memory: A review with meta-analysis. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 37 (8), 1645-66.

Researchers have consistently focused on cardiovascular exercise’s role in preventing coronary heart disease, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, some cancers and other chronic diseases. Other studies have examined whether cardiovascular exercise reduces stress, depression and anxiety (Ahiskog et al. 2011).

Yet more studies have delved into how cardiovascular exercise affects decision-making, attention and speed processing. In 2013, Roig and colleagues went a step further, summarizing several recent studies exploring how cardiovascular exercise triggers neurobiological mechanisms that influence memory processing. Their findings address several important questions of interest to fitness professionals.

What Are the Key Types of Memory?

Research divides memory into two familiar categories: short-term and long-term.

Short-term memory, also called working memory, retains information over brief periods from a few seconds to 1–2 minutes (Roig et al. 2013). As information comes in, the brain begins processing it immediately. Examples of short-term memory tasks from the research include memorizing a series of random digit numbers (0–9), remembering pairs of words, recalling a list of words presented orally, and/or recalling names associated with people or pictures (Roig et al. 2013). Short-term memory tests involve almost-instantaneous retention.

In contrast, long-term memory research explores memories retained more than 2 minutes after an information stimulus. For instance, long-term memory tasks from the research include identifying 18 photographs of faces presented 30 minutes earlier; recalling details of a short history story 30 minutes after it has been read; and/or recollecting images presented visually 15 minutes before (Roig et al. 2013).

Scientists further categorize long-term memory as either declarative or nondeclarative (Squire 2004). Declarative memories consciously recall facts and events that we experience, including such things as news events occurring around the world. Nondeclarative memory retains previous experiences that help us perform a task without our conscious

awareness; for example, riding a bike or tying a shoelace. Squire suggests the brain has multiple memory systems that operate together to support our behaviors.

How Does Acute Cardiovascular Exercise Affect Short-Term Memory?

Researchers typically use brisk walking, cycling or running in studies on cardiovascular exercise and memory. The acute (or immediate) effects of cardiovascular exercise on short-term memory involve the use of submaximal to maximal bouts of exercise. Although results vary from study to study owing to research design differences, the data indicate that acute bouts of cardiovascular exercise improve visuospacial short-term memory more than verbal-audio (i.e., listening) short-term memory (Roig et al. 2013). Visuospatial memory includes visual perception of spatial relationships among objects, such as interpreting directions on a map.

The research suggests that walking is the most effective acute cardiovascular exercise for improving short-term memory (Roig et al. 2013). In addition, the effects of acute cardiovascular exercise on short-term memory are better when the exercise bout lasts less than 20 minutes and is performed at a low intensity (<40% of heart rate reserve, such as brisk walking). Fitness level has no bearing on acute cardiovascular exercise’s effect on short-term memory (Roig et al. 2013).

Alas, the short-term memory of young adults (aged 18–24) tends to see the most improvements from acute cardiovascular exercise (Roig et al. 2013). Roig and colleagues summarize that acute cardiovascular exercise improves short-term memory by priming the molecular processes involved in the encoding and consolidation of newly acquired information.

How Does Long-Term Cardiovascular Exercise Affect Short-Term Memory?

Long-term cardiovascular exercise (>6 months) has different effects on short and long-term memory. This type of exercise improves verbal-audio shortterm memory (e.g., listening to lectures, engaging in group discussions, listening to audiobooks on tape). Combining walking, running and cycling maximizes the effect of long-term cardiovascular exercise on short-term memory. Long-term cardiovascular exercise involving medium duration (20–40 minutes) and light to moderate intensity (40%–59% of heart rate reserve) shows the greatest effect on short-term memory. After long-term cardiovascular exercise, it is once again young adults who show the greatest gains in short-term memory.

How Does Long-Term Cardiovascular Exercise

Affect Long-Term Memory?

Long-term cardiovascular exercise initially appears to provide only negligible improvements in any subcategory of long-term memory (Roig et al. 2013). Further investigation of the literature, however, suggests that long-term cardiovascular exercise may meaningfully delay some age-related memory impairments.

Erickson and colleagues (2011) conducted a yearlong study with 120 men and women (average age 66), none of whom were diagnosed with dementia. Sixty subjects served as a control group and did stretching exercises three times a week. The experimental group engaged in cardiovascular walking exercise three times a week, gradually working up to 40 minutes per session. The walkers progressively increased their walking intensity from 50% to 75% of heart rate reserve during the 12 months of the study.

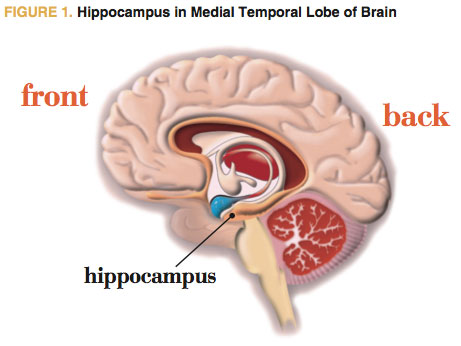

Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain of each subject was completed at baseline, halfway through the intervention and at the end. Researchers were particularly interested in whether exercise affected deterioration of the hippocampus in the brain. The hippocampus (see Figure 1) is in the medial temporal lobe of the brain and forms part of limbic system. It consolidates new information from short-term memory to long-term memory and is associated with visuospatial memory, learning and emotions. Deterioration of the hippocampus in the brain leads to memory loss in late life.

Erickson et al. (2011) showed that progressively increasing duration and intensity of cardiovascular exercise increased hippocampal volume 2% over the course of the year. The stretching control group showed a 1.4% decline over the same time period, which the authors described as a normal expected decrease with aging. These researchers proposed that the increase in hippocampus size translates to an improvement in memory function and theoretically helps to reduce the risk of cognitive impairment. They also emphasized, however, that the extent to which cardiovascular exercise can modify the size of the hippocampus in later life is unknown.

Finally, Roig et al. (2013) add that the research indicates study subjects with at least an average fitness level have the best long-term memory gains from participation in regular cardiovascular exercise.

Points to Remember

Short-term memory and long-term memory are distinct and yet complementary. Acute cardiovascular exercise (<20 minutes, low intensity) appears to facilitate a person’s short-term perception of spatial-relationship tasks (think of a personal trainer rearranging the exercise equipment in a fitness facility to adapt to client traffic flow and usage).

Long-term cardiovascular exercise appears to improve short-term memory

and prevent deterioration of the hippocampus. Thus, sustained long-term cardiovascular exercise may delay the memory loss often observed later in life. This new research supports the philosophy that the road to improved memory health has no finish line.