Exercise Prescription Is the Magic Pill

The association between a physically active lifestyle and good health cannot be denied. The active and fit live longer, healthier lives, while the sedentary and unfit tend to suffer prematurely from chronic disease and die at a younger age.

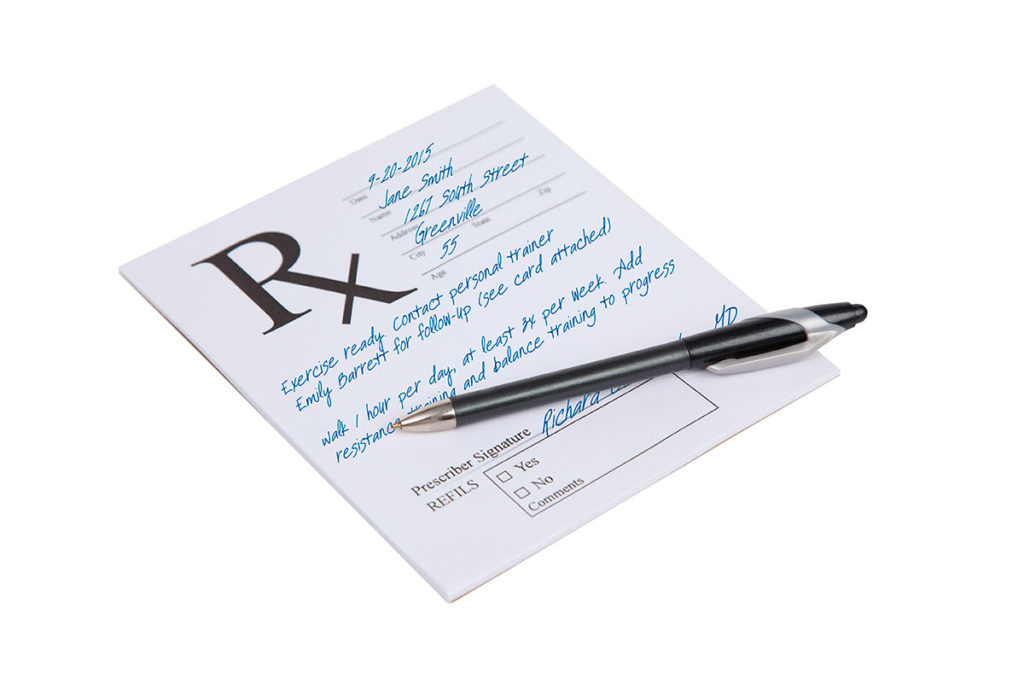

Public health experts worldwide have been sounding the alarm about the risks of obesity, yet evidence suggests inactivity is an even bigger risk factor. In fact, if exercise were a drug, it would be the most powerful ever prescribed. Hence the creation of the Exercise is Medicine® (EIM) Global Health initiative, which urges physicians worldwide to use an “exercise vital sign” to assess people’s fitness and to offer a proper exercise prescription—typically walking at a moderate pace for 30 minutes on 5 or more days each week (see Table 1).

This simple prescription has the potential to prevent and treat more diseases than any other therapy. Furthermore, strength and flexibility training can also be powerful medication to help with the aging process and to improve quality of life. While physicians often recommend exercise to patients, we acknowledge that fitness professionals have the training and skills to help people

adhere

to these recommendations. Doctors and fitness pros joining forces to improve public health needs to become the new normal—and EIM is working to make that happen.

Research suggests a linear relationship between physical activity and health status, and an association between disease and inactivity in every subgroup of the population (Lancet 2012). Yet mainstream U.S. medicine has mostly ignored this research and failed to integrate exercise into standard disease treatment and prevention paradigms. This has to change, because the Affordable Care Act is ensuring that more and more Americans have access to health care and we are quickly realizing that our current healthcare system with its focus on pills and procedures is not financially sustainable. We must shift the focus to keeping people healthy, and we know the best way to do it: Avoid tobacco, eat a healthy diet and exercise daily!

While smoking rates have plunged over the past 50 years, the results on healthy diets have been a massive failure: Americans have grown even fatter, and we can’t find five nutrition experts who can agree on the best diet; with diet books and weight loss programs of their own to promote, most have conflicts of interest.

Mainstream medicine, meanwhile, has not embraced exercise because there is no clear way to profit from patients becoming more active. The people who actually pay for health care, however, have an incentive to notice the ample evidence proving that fit, healthy people cost us less to care for, miss less work and stay more productive.

The time has come for physicians to strongly advise patients to engage in regular physical activity, particularly patients facing chronic diseases such as diabetes, heart disease and high blood pressure. Moreover, fitness professionals and health clubs can play a pivotal role in helping to ensure that people heed their doctors’ prescriptions to exercise.

A Pill Called Exercise

Imagine a pill that confers the proven health benefits of exercise. Physicians would widely prescribe it, and healthcare systems would see to it that every patient had access to this wonder drug. Patients clearly need a prescription of exercise, but little has been done in an organized fashion to help them get it. Instead, we keep overemphasizing and expanding an array of high-priced and often marginally effective pills and procedures.

Nations around the world have a lot at stake in getting citizens more active. The World Health Organization recently recognized physical inactivity as the fourth leading risk factor for global morbidity and premature mortality (WHO 2009). The cost of medical care for inactive patients dwarfs the cost of caring for active ones (Anderson et al. 2005). Further, we may be looking at a generation of children who are so sedentary they could be the first generation to live shorter lives than their parents. Where will we get our next generation of police officers, firefighters and soldiers with the fitness and strength needed for these demanding jobs? The public health threat of physical inactivity will only get worse if organized medicine does not act.

Physicians must become more ardent advocates for exercise. They should ask about it at every patient visit, and every patient’s activity level should be seen as a vital sign. After all, it is arguably the single best indicator of health and longevity.

Furthermore, we need a melding of the fitness and healthcare industries. Physicians should be able to refer patients to a fitness professional who can help them achieve their exercise goals. The benefits are just too great to ignore.

Obesity vs. Inactivity: Which Is More Important to Public Health?

Growing concern over the global obesity epidemic has masked the twin epidemic of inactivity. In June 2013, the American Medical Association voted to classify obesity as a disease (AMA 2013). Unfortunately, obesity is a nebulous diagnosis most often defined by body mass index, essentially the ratio of one’s weight to height. BMI is a terrible measure because it fails to account for a person’s body composition—extra muscle and extra fat both elevate it.

In fact, BMI labels more than one-third of Americans—and 56% of NFL players—with a chronic disease. It is a stretch to think that measuring and recording BMI can improve health outcomes when it is such an error-prone gauge for obesity (Sport Digest 2013).

More concerning is the fact that we have only three funded medical treatments for obesity: bariatric surgery, weight loss drugs and nutrition counseling. It is interesting to note that the most expensive obesity treatment by far (bariatric surgery) is also by far the one most often covered by health insurance. Is stapling the stomachs of obese patients really the best way to spend healthcare dollars? Given the proven effect of exercise in helping to prevent obesity and, more crucially, in mitigating its harmful effects, it bears asking: Why is exercise not funded as a medical treatment?

It’s because the healthcare system’s approach to dealing with almost every disease is simply to prescribe a pill or a procedure. Even so, physicians see the limited utility of weight loss pills and procedures firsthand—while they may help in the short run, the long-term effects are rarely significant. We’ve also observed the utter failure of public health messaging on obesity over the past 20 years. Telling people they’re too fat, blaming food companies and pushing short-term, feel-good solutions like bans and taxes have made us nothing but fatter.

Weighing the “Obesity Paradox”

Another important factor to consider is that somebody with a normal BMI who develops a chronic disease like cancer, heart disease or diabetes generally dies sooner than someone with the same disease who is overweight or obese. Researchers have termed this the

obesity paradox,

and while the reasons for it are not quite clear, it is plain that being thin is not always healthful (Lavie, Milani

&

Ventura 2007).

That’s why we are seeing an ongoing debate about the relative importance of “fitness vs. fatness.” And the evidence shows that a person is better off being fit and fat than being unfit and skinny. To put it another way, a sedentary lifestyle is a bigger risk factor for morbidity and mortality than is a mild to moderate level of obesity.

More significantly, evidence proves that the best way to combat the harm of obesity is to get people to be more active, which is much easier than getting them to lose weight. Let’s face it: Most everyone can go for a walk.

The key is to shift some of the public health focus off obesity and onto physical activity. People need permission to be fat and still be healthy. The way to do it is by getting them more active.

The Exercise Vital Sign

A basic tenet of the EIM initiative is that a patient’s weekly quantity of physical activity should be regarded as a vital sign. EIM suggests that every patient should have his or her physical activity habits assessed and documented and then receive a proper exercise prescription. The Exercise Vital Sign (EVS) is a simple way to do this while also putting the topic of exercise in the exam room with every patient (Sallis 2011).

Kaiser Permanente health care has effectively used an EVS in Southern California since October 2009. Since then, the method has been rolled out to all other Kaiser regions. The EVS at Kaiser is administered during the assessment of traditional vital signs—blood pressure, pulse, respiration and temperature. Each patient is asked, “On average, how many days per week do you engage in at least moderate to vigorous physical activity like a brisk walk?” Then a follow-up question asks, “On those days, how many minutes do you engage in physical activity at this level?” The medical assistant taking the EVS uses a computer to input the patient’s response, indicating 10, 20, 30, 40 or 50 minutes, etc. The computer multiplies the two responses to provide a minutes-per-week, self-reported assessment of moderate to vigorous exercise.

The Kaiser electronic medical record then automatically displays the minutes per week of moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA) that the patient reports. Adults doing less than 150 minutes per week of MVPA are advised that they should increase their activity levels.

The Kaiser Permanente EVS has gained remarkable acceptance in the roughly 5 years it has been used in Southern California—well over 90% of adult patients have an EVS recorded on their chart. What’s more, among patients over age 65, 96% have an EVS on their chart, which is significant because elderly patients stand to benefit the most from doing regular exercise (Coleman et al. 2012).

We also found that like most other populations studied, Kaiser patients often fail to meet U.S. Physical Activity Guidelines. Our data showed that 36% of patients reported being completely sedentary, with no physical activity in a typical week. We also found that 33% were insufficiently active, reporting they typically engaged in 10–149 minutes per week of MVPA. Further, we found that only 30% of patients were currently meeting the U.S. physical activity guidelines of 150 minutes per week or more of moderate to vigorous physical activity.

The Role of the Fitness Professional

While walking is generally considered the default exercise prescription, patients need more than simply being told to walk. Walking is great for cardiovascular health, but strength and flexibility are also important for staying healthy and aging gracefully. Studies have shown that strength training not only benefits cardiovascular health but also retards the loss of bone density and lean muscle mass that accompanies aging.

Flexibility is often neglected as we age; moreover, the normal loss of motion at most aging joints can be a strong risk factor for falls and can diminish one’s functional capacity and quality of life. Strength and flexibility are key components of fitness that are neglected when physicians offer a walking-only prescription. Fitness professionals have the experience and abilities required to instruct patients on the proper ways to improve these key components of fitness.

While most physicians acknowledge the critical importance of fitness, they lack the time or expertise to give patients a customized program to improve their fitness. Most physicians are also confused by the myriad fitness certifications and unsure which fitness pros are best trained to help their patients.

Furthermore, most current health plans lack coverage for fitness professionals working with patients. This has to change, but change will happen only if fitness professionals and healthcare organizations get together and push for needed reforms in reimbursement. I wouldn’t think of managing my diabetic patients without the help of a dietitian, and it makes no sense that I cannot have a fitness professional working with that same patient, since studies show that keeping diabetic patients active does as much to improve their health as eating the right diet.

Take the First Step

The evidence is clear that exercise is a very powerful tool for treating and preventing chronic disease, mitigating the harmful effects of obesity and improving mortality rates. In addition, exercise has a powerful effect on functional capacity and quality of life. In effect, Exercise is Medicine and many experts consider physical inactivity to be the major public health problem of our time. For these reasons, physicians have a responsibility to assess physical activity habits in their patients, to inform them of the risk of being inactive and to provide a proper exercise prescription.

The easiest way to do this is by using an Exercise Vital Sign to assess the minutes per week of moderate or more vigorous exercise that a patient is doing. Based on the EVS, the physician should either congratulate the patient on meeting current physical activity guidelines or encourage the patient to meet these guidelines. While walking is generally considered to be the default exercise prescription, many health benefits can be gained by also improving strength and flexibility.

It is clear that fitness professionals and health clubs have a role to play in helping patients to fill a proper exercise prescription, and it is incumbent on leaders in the healthcare and fitness industries to work together to make this happen. n

Robert Sallis, MD, FACSM, FAAFP, is codirector of the Sports Medicine Fellowship at Kaiser Permanente Medical Center in Fontana, California. He is also a clinical professor of family medicine at the University of California, Riverside, School of Medicine.