Understanding and Preventing Common Running Injuries

Long-distance running continues to attract new enthusiasts throughout the world (Tonoli et al. 2010); its unique combination of benefits can help people to control their weight, improve cardiovascular function and fend off a host of chronic health problems (van Gent et al. 2007; van Middelkoop et al. 2008). But for all these advantages, running is hard on some parts of the body, often leading to lower-extremity injuries (van Middelkoop et al. 2008).

What Are Running Injuries, and How Prevalent Are They?

O’Toole (1992) describes a running injury as “a condition that causes an athlete to decrease his/her weekly training mileage,” typically happening because of repetitive microtrauma injuring the weakest anatomical location in a vulnerable structure. Summarizing the research to date, O’Toole estimates that 45%–70% of endurance athletes suffer from a running injury within any 12-month span.

Recreational runners have it even worse: Ellapen et al. (2013) report that 90% of 200 recreational half-marathon runners experienced one or more running injuries within a 12-month training period. And novice runners have higher injury rates than experienced runners (Tonoli et al. 2010; Fredericson & Misra 2007). Experienced runners tend to have less risk of injury because they develop an innate ability to recognize the onset of an injury and keep it from worsening (Fredericson & Misra 2007).

What Are the Most Common Running Injuries?

Studies suggest knee-related injuries are the most common, accounting for 26%–50% of all lower-extremity injuries (Ellapen et al. 2013; van Gent et al. 2007; O’Toole 1992). The foot, ankle and lower leg have a combined occurrence rate up to 50%. The hip and low back are also vulnerable to running injuries (O’Toole 1992).

What Are the Most Common Injury Causes?

Research identifies these common training errors that lead to running injuries:

- rapid increase in weekly mileage (O’Toole 1992)

- continuous high mileage (Runners averaging 50–70 miles per week have a 50% chance of injury [O’Toole 1992]; Fredericson & Misra [2007] suggest the risk begins to increase meaningfully at ≥40 miles per week.)

- abrupt change in running surface (O’Toole 1992)

- failure to follow hard training days with light training days (O’Toole 1992)

- wearing inadequate or worn-out footwear (O’Toole 1992)

- running on uneven surfaces (O’Toole 1992)

- returning to previous mileage too fast after a layoff (O’Toole 1992)

- running 12 months without a break from training (van Gent et al. 2007)

- history of previous injuries (van Gent et al. 2007)

- too much hard interval training (O’Toole 1992)

- training for competition (Fredericson & Misra 2007)

- muscle imbalances near a lower-extremity joint and/or inadequate muscular strength or range of motion (O’Toole 1992)

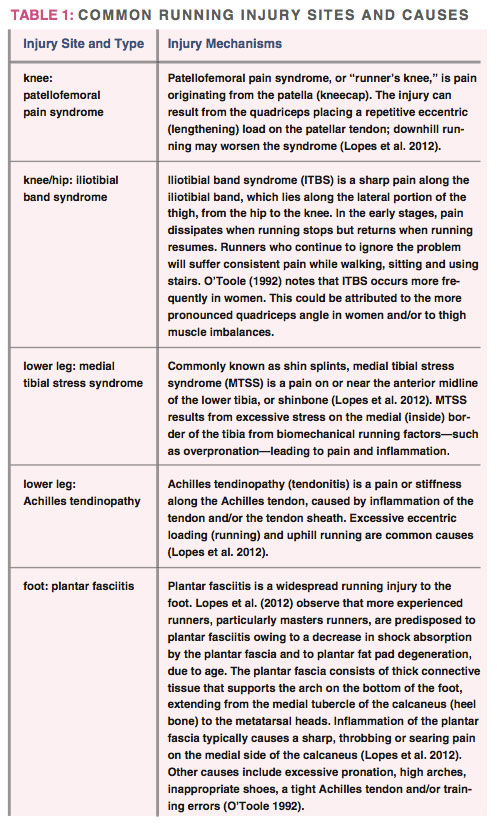

See Table 1 for common injuries and their causes.

What’s the Best Way to Treat Running Injuries?

Treatment should begin with rest, ice and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs) to reduce inflammation. A decrease in inflammation improves the range of motion of an injured joint and speeds up the healing process. Fredericson & Misra (2007) say stretching has not been substantiated as a way to prevent injury; conversely, O’Toole (1992) proposes that stretching exercises may help develop appropriate ranges of motion to prevent scarring and shortening of the healing tissue after injury.

Clients with running injuries need to consult with a medical practitioner or therapist to choose the best rehabilitation strategy. Clients also need to understand that people heal at different rates and should seek a doctor’s advice on the treatment plan that will best suit their body’s needs (O’Toole 1992).

While recovering and rehabilitating, it is important for runners to stay fit by cross-training (Fredericson & Misra 2007), which gives the injury enough time to heal (O’Toole 1992). Examples to consider include running in water, swimming, biking and cross-country skiing (Fredericson & Misra 2007).

Strengthening muscular deficiencies can improve the balance of forces around the injured joint, and eccentric training can help during the rehabilitation phase (O’Toole 1992). Strengthening the hamstrings eccentrically after an overuse injury of the knee is one example.

Running Injuries: Final Thoughts

Personal trainers need to educate clients about the many factors that lead to running injuries. Clients must pay close attention to the overall training progression, moderately increasing distance and the number of hard running days. O’Toole (1992) says multiple studies recommend the 10% rule: Increase mileage no more than 10% each week.

It is important to schedule days off for recovery and avoid excessive down- hill running on consecutive days, and it may help to regularly vary running direction on a track or road (O’Toole 1992). Enthusiasts who train properly will reap the health benefits of running for years to come.