Is Obesity Contagious?

We often hear about an “epidemic” of obesity. This past year, the American Medical Association deemed obesity a disease (AMA 2013). A lot of people have a hard time associating the term “disease” with obesity because body weight is within our control . . . or is it?

Obesity has many properties of diseases, including a genetic prevalence and associations with other diseases or conditions like diabetes, hypertension and certain cancers. Obesity causes losses of certain functions and creates pathological conditions that increase morbidity.

So obesity is a disease, but can we catch it the way we catch a cold? Not exactly—obesity is not an infectious pathogen. Still, a growing body of research has uncovered widespread sociological and cultural factors that influence people’s diet, physical activity and body weight. Simply exposing ourselves to certain “toxic environments” can increase our risk of becoming obese. Our genes, gender, locality, ethnicity and social habits create a complex interplay that ultimately contributes to our obesity epidemic.

This article will summarize research on the interrelationships between “social factors” affecting obesity and will share tips on how you can help clients not only cope with toxic environments but also create healthy ones for themselves. By having knowledge about influences that may contribute to obesity, you will be more effective in treating your clients and aiding them in avoiding or minimizing the “hidden factors” that could be sabotaging them.

Birds of a Feather Fatten Together

Friends, family and social acquaintances all influence our choices of diet and physical activity. One study into the link between social networks and body weight over three decades found that people’s likelihood of obesity is

- 37% higher if their spouse is obese,

- 40% higher if a sibling is obese, and

- 57% higher if friends are obese (Christakis & Fowler 2007).

David Rand, a Harvard research scientist who worked on the Framingham Heart Study, summed it up this way: “The more obese people you have contact with, the more likely you are to become obese. It may be that if you have a lot of friends with unhealthy eating habits, you wind up with similar eating habits” (Hellmich 2010).

A study in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition found complex interactions between gender, age and food intake (Salvy et al. 2011). Young boys and girls (aged 5–7) consumed fewer unhealthy snacks in the presence of their mothers than in the company of friends. Teen girls (aged 13–15) did the opposite, eating fewer unhealthy snacks and more healthy snacks when they were with their friends than when they were with their mothers. Salvy and colleagues concluded that parents may discourage unhealthy eating in younger children. On the other hand, adolescent girls want to show their female friends that they eat healthy foods. Social context has less influence on the eating habits of teenage boys (Salvy et al. 2011).

Harvard researchers associated with the Framingham Heart Study say that having four obese friends doubles a person’s chance of becoming obese, compared with having no obese friends (Hellmich 2010). Being in a class with other overweight children even influences weight gain in elementary school children. A large study at the University of Arkansas assessed the weight gain and obesity patterns of 341,876 elementary school students from 2004 to 2010. The study found that

- a typical student (normal BMI) gained extra weight if he or she was in a class with a larger share of obese or overweight classmates; and

- the same typical student lost weight if the larger share of classmates were skinny (Morin 2013).

Eating (or Not) to Impress or Not to be Depressed

Studies have shown that our moods can influence what we eat. Likewise, romantic interest will affect our food choices and quantities.

One research project noted that men and women will eat less or try to match the quantity and quality of food in the presence of a stranger of the opposite sex in order to gain positive approval. In general, women conform more than men because women take greater responsibility for forming positive interpersonal bonds and men have a greater sense of independence and distinctiveness (Salvy et al. 2007).

When linking moods and diet, we have to examine whether people eat poorly because they are depressed, or whether they are depressed because they are eating poorly. Of course we cannot discern all of these links, but some studies have made intriguing discoveries. Isnard et al. (2003) linked binge eating to anxiety and depression levels. Data showed that the stronger the mental problem was, the more binge eating took place. Christensen and Brooks (2006) found that women were more likely than men to respond to negative moods and distressing events by craving and consuming empty calories.

There is also a chemical relationship. Richardson (2003) reviewed studies and concluded that deficiencies in omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids may play a role in certain mental disorders, including dyslexia, depression, autism and bipolar disorder. Boosting omega-3 (EPA) intake was shown to improve brain functioning and to be helpful in managing depression and schizophrenia.

On a similar note, two studies in 2013 found a significant relationship between the active form of vitamin D and rates of depression. Milaneschi et al. (2014) found in a large cohort study that people diagnosed with depression have low levels of vitamin D, with levels being lowest in people with the most severe depression. Omega 3 and vitamin D are often missing in subcultures that lack fresh fish, milk and leafy greens. Thus, the interrelationship between socioeconomic class, depression, food consumption and obesity may warrant more investigation.

Do Our Genes Make Us Overweight?

It is difficult to tease out how much of obesity has to do with genetics and how much is associated with diet, body image, physical activity and how we are raised with food. Studies tracking children to adulthood are rare, but some research finds that the likelihood of a child becoming obese doubles or triples if both parents are obese. Among obese 3 to 5-year-olds, the chance of adult obesity increased from 24% if neither parent was obese to 62% if at least one parent was obese (Whittaker et al. 1997).

The likelihood climbs significantly as a child ages. For example, a child who is obese at age 1–2 has only an 8% chance of being obese as a young adult if the parents are not obese. However, for a child who is obese at 6 years old, the likelihood jumps to more than 50%, compared with about 10% for a non-obese child (Whittaker et al. 1997).

A Stanford study of 74 boys and 76 girls found that 64% of children with overweight parents became overweight, but only 16% of children with normal-weight parents became overweight. The researchers reported that temperament played a role in the weight of both parents and children (Agras et al. 2004).

Some studies show a strong genetic component to childhood obesity, with evidence for modest heritability of taste preferences (Breen, Plomin & Wardle 2006; Wardle et al. 2008). Although the genetic component is significant, social and familial influences can’t be isolated.

Culture Drives Eating Habits

Dietary habits and traditions are as diverse as the languages and cultural traits of our planet’s population. Across many cultures, dining has traditionally been a time to relax and catch up with family and friends, but the convenience of fast food is changing the way people eat in almost every country.

And it’s not just fast food; it’s also too much food. In the U.S. and abroad we have a major case of portion distortion (the Super-Size Me syndrome), where increases in serving sizes and fat/sugar content closely parallel the rise in obesity.

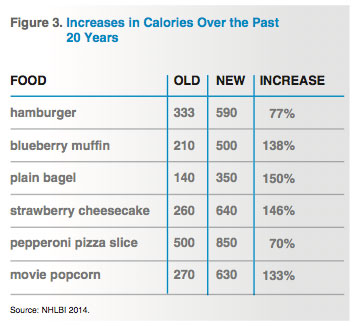

Studies from Rutgers University and the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, show that in most cases, 20 years ago we ate less than half as many calories for a given food as we do now (NBC News 2006). Take a quick peek at Figure 3, “Increases in Calories Over the Past 20 Years,” for some examples of portion distortion.

Then there is our newfound favor for excess flavor. Coffees used to have cream and sugar but now have mocha latte with whip cream, caramel and chocolate sprinkles. Many restaurants consider the “doggie bag” a standard feature, as few people can finish the monster portions in one sitting. Dishes, bowls and cups are all bigger, increasing our frame of reference. And because restaurants have increased their serving sizes, we now serve ourselves more when eating at home (NBC News 2006).

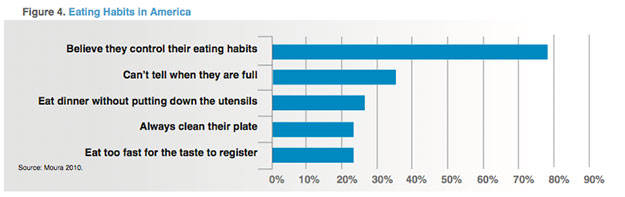

Fast eating is another major problem. It takes about 20 minutes for us to fully digest food past the stomach and for satiety signals to register in the hypothalamus, triggering the urge to stop eating. Most people wolf down their food far faster than this and feel overfull after the meal has been completely digested.

Figure 4 shows statistics on eating habits in America.

What Can You as a Trainer or Health Coach Do?

Since dietary influences are so numerous, you’ll need to help clients develop a defense system. Remember, some food values and activities will be deeply ingrained from childhood and will change slowly and perhaps not entirely. The first step is understanding that obesity requires changes on several levels.

The next step is taking a good look at a client’s cultural and social environment. Ask the client to step outside his “box” and look at how many fast-food restaurants surround his neighborhood. Is food a reward? Were his parents or siblings overweight or obese? At family gatherings, is food a centerpiece? When going out with friends, does he eat differently to impress them?

Urge the client to answer these and other questions honestly, and then rank your client’s surrounding and peer group on a scale from 1 to 5. If the average is more than 3, you are fighting an uphill battle. Coach your client to minimize exposure to situations and environments that will sabotage the hard work put in at the gym. Also, arm the client with techniques to deal with situations as they arise.

Using Social Influence and Media to Battle the Bulge

The same social influences that help people gain weight can be used to fight the fat. Low self-esteem and social support, weight-related teasing, and greater pressures to lose weight were associated with adolescents’ negative self-esteem, body image and eating attitudes (Ata, Ludden & Lally 2007). Aim, therefore, to limit the tendency among clients to compare themselves with others.

Encourage clients to find support groups online. A 2011 study in The New England Journal of Medicine found no difference e between online (distant) support and face-to-face support for weight loss (Appel et al. 2011). Online weight loss support communities offer a viable option. Pick one that your client can identify with. A good starter might be SparkPeople®, 3 Fat Chicks on a Diet! or Womens-Health.com for your female clients. The major weight loss programs also have online forums.

Take your clients out to a meal, or at least discuss appropriate portions. Encourage involvement in fun activities like races, and steer them toward healthy, upbeat people of their own age and gender. Speaking of companionship, be an advocate for “man’s best friend.” Several research reports have shown that people with dogs get significantly more activity from walking than those without, and the nurturing factor is good for their mental health.

Finally, urge clients to avoid sitting and reduce screen time. A recent study from the University of Minnesota School of Public Health found that obesity was more prevalent among parents and children who clocked more screen time. Parents who had engaged in more screen time as children were more likely to have offspring who watched more than 2 hours of television per day. And body mass index, waist circumference, visceral adipose tissue and percent body fat were all higher in parents and children who accrued more screen time (Steffen et al. 2013).

Figure 6 demonstrates the many interrelationships involved with being overweight or obese. The combination of multiple influences, some of them mutual, complicates the challenge of addressing obesity.

Social and environmental factors affect moods, behaviors and attitudes toward exercise and food choices. If we take a holistic perspective that accounts for the people we know and the places where we live, we can find the best ways to battle the obesity epidemic and reduce its contagiousness.