Small Exercise Equipment for Big Impact

Adopt a multistep approach and get more done with limited options.

Using small exercise equipment in classes and group training had always been a good, creative option for fitness professionals. The more toys, the better, it seemed, especially if we knew how to use them well and could integrate them into meaningful workouts.

Then came the pandemic, arguably the biggest disruptor in the fitness industry’s history. Whether we wanted to or not, we were forced to switch gears as workouts moved almost immediately from gyms and studios to living rooms, garages, bonus rooms—wherever our clients and class participants could find a space to exercise.

Before COVID-19, people could easily buy small equipment off the shelf from big-box stores or online from multiple sellers. But as the virus spread and people raced to purchase not only toilet paper but also dumbbells, demand suddenly outpaced supply. Since then, the lessons we’ve learned and our combined experiences have challenged us to deliver fitness in unique, innovative ways.

In everything we do as a collective force of positivity, change is a constant and creativity is paramount. And so we did what we always do—we made it happen. Instructors and trainers shared tips on how to assemble homemade equipment—making weights from milk jugs filled with sand, for example, and using panty-hose as resistance bands. With encouragement from one another, we “stayed calm and carried on,” and now we’re smarter and stronger.

Whether you’re instructing virtually, outdoors or back in the studio, small exercise equipment still tops the list of effective do-anywhere, use-anytime tools. What are the best ways to utilize small equipment, and how can you make the experience even better for yourself, your clients and your class participants? Here are some tips for building your program.

Read the Room

Before getting started, step into participants’ mindsets to get a good feel for how to create the workout. Are people ready to go back to training as they did before, or are they hesitant? If your students have returned to the studio, are they comfortable picking up and using equipment? This is an important factor to think about as your facility opens. Recognize that more touch points require greater vigilance in your cleaning and disinfecting protocols. Consider sending out a brief survey or at least soliciting questions and suggestions.

Also, keep in mind that, 18 months into working out from home, many people may not be in the shape they think they’re in. The hard truth is that, even if your members exercised on their own and kept a routine going, their efforts probably fell short of the rigors needed to meet certain goals. People tend to work out harder and more effectively in groups or supervised sessions, and your clients may need a little ramping up at the beginning. To take their minds off the hard work and help them focus on the joy of movement, figure out fun ways to use small pieces of equipment.

The Nuts and Bolts (and Balls and Bands)

Different kinds of small equipment suit some movements better than others.

Moving on to logistics, a good way to begin is by choosing pieces that can multitask. For example, if a balance board can only be used for balance training but a stability ball can be used for balance plus cardio, strength and flexibility, go for the stability ball, as it gives you more bang for your buck. And remember to adopt a progressive approach to exercise and equipment planning. Let the foundational move (e.g., a squat) be the “leading lady” and allow the small exercise equipment and secondary fitness components to be the “supporting actors.”

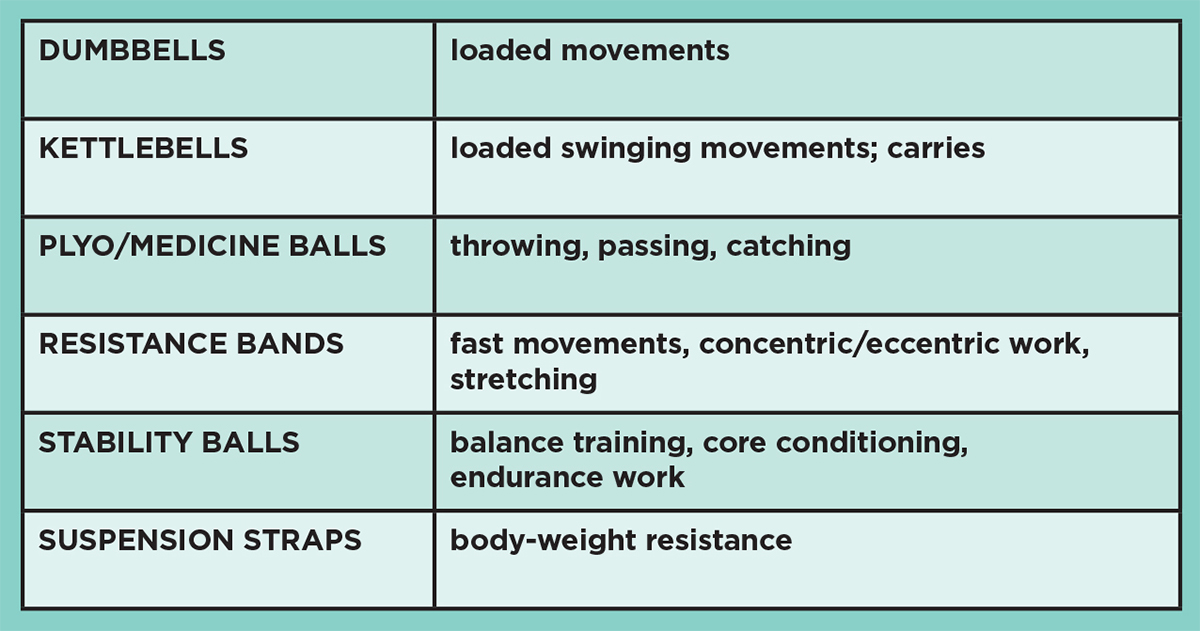

While multitasking potential is useful, different kinds of small equipment suit some movements better than others. For example, a 10-pound kettlebell and a 10-pound plyoball are similar only because they’re small pieces of weighted equipment. You’d forgo using the kettlebell in a catching exercise and choose the plyoball instead because, obviously, a ball is better suited for throwing and catching. The same suitability rule applies for speed work: If you want to add fast movement training with load, choose a resistance band over dumbbells. (See “Which Small Equipment Will Work?,” below.)

If you’re teaching virtually, make sure everyone knows ahead of time what they’ll need for the workout, and try to choose options that can be swapped out with common household items (see “Nontraditional Small-Equipment Options,” below). You might also consider creating your own simple product bag to offer for sale. For example, buy cinch bags and fill them with a small weighted ball, resistance bands, a jump rope and maybe a little foam roller. Otherwise, to be inclusive, think simply as you design your program. Perhaps do an entire session with just one dumbbell or share all of the wonderful things you can do with a stability ball. Most people will likely be wowed by the possibilities.

Prepare for Success with Small Exercise Equipment

Once you’ve reflected on your participants’ needs and abilities and considered the versatility and uses of various types of equipment, you can begin to carefully plan your session. Start by determining its duration, because how you prepare for a 30-minute workout will differ slightly from how you’d design a 60-minute program. With shorter sessions, specifically more advanced offerings, you’ll need to consider how to include more integrated muscle movements, such as those used in combination exercises that train the lower body, upper body and core at the same time.

Equipment inventory is the second consideration—what and how much. Although you can mix and match, this may create challenges around sharing (not ideal at this moment in time) and how to cue effectively when participants are using different tools. If you teach circuit-style classes, make sure all attendees use their own identifiable pieces of equipment. At the end of the day, err on the side of simplicity.

Now comes the actual program—deciding which exercises to choose, what equipment you’ll need, and which modifications you’ll use (progressions and regressions). Planning a workout is like baking a cake. Each recipe ingredient adds to the final product, but you don’t just throw everything into the pan at once and hope the cake works out.

In a three-step “recipe” approach to planning small-equipment workouts, begin with foundational movements. Include squatting, lunging, hinging, pushing and pulling, rotation, planks, and some lifting and gait work. Don’t necessarily do these in that particular order or in separate steps, but do include each element by the end of the workout.

Next, look at ways to increase complexity by including multiple planes of motion, motor learning or greater task complexity. In essence, you’re training participants to move through life. Human bodies need to absorb, produce and transfer forces, and you can cater to these needs by incorporating a range of movement principles—varying load, lever length, hand and foot placement, centering, tempo of movements, and/or transitions. Power also comes into play as a means of movement complexity and is the last addition in this three-step approach. See “Key Movement Principles for a Varied Workout,” below, for ways to add the power ingredient.

Breaking It Down

Whether you’re instructing virtually or in person, including small exercise equipment in your sessions and classes is still a popular method for motivating people.

In summary, creating interesting small-equipment exercises involves

- choosing a foundational movement;

- increasing movement complexity by adding equipment (or another challenge); and

- increasing power.

Fortunately, this approach to teaching in a group fitness setting takes into consideration diverse abilities, plus it provides a teaching recipe. For example, a wide-squat woodchop using dumbbells is an advanced exercise. The squat is the foundational move, the wide stance changes the foot position, the low-to-high swing across the body adds rotation, and the dumbbell adds load. Doing the woodchop quickly dials up the power output. A new exerciser could stay at level one, simply performing the wide squat without the upper-body movements, whereas an intermediate participant might add the diagonal move without load, and the more advanced exerciser could perform all three parts.

Regardless of ability, always “bake in” progression and regression. Progression—important as a person’s fitness improves—can be accomplished by boosting exercise intensity or complexity. Regression shouldn’t be thought of as just “the easier exercise,” but rather as a way to find the best exercise at the correct intensity or movement for a student’s current ability. It’s not harder or easier, but rather the right choice. See “Give These Small-Equipment Exercises a Try!,” below, for more ideas.

We’re all riding the wave of change and looking for ways to create new opportunities for ourselves and our participants and clients. The truth is, we have more ways to share our knowledge than ever before, particularly when it comes to designing small-equipment programs. Whether you’re instructing virtually or in person, including small exercise equipment in your sessions and classes is still a popular and viable method for motivating people. Keep it simple, check off the foundational boxes, consider different fitness levels, and teach an effective and functional full-body workout.

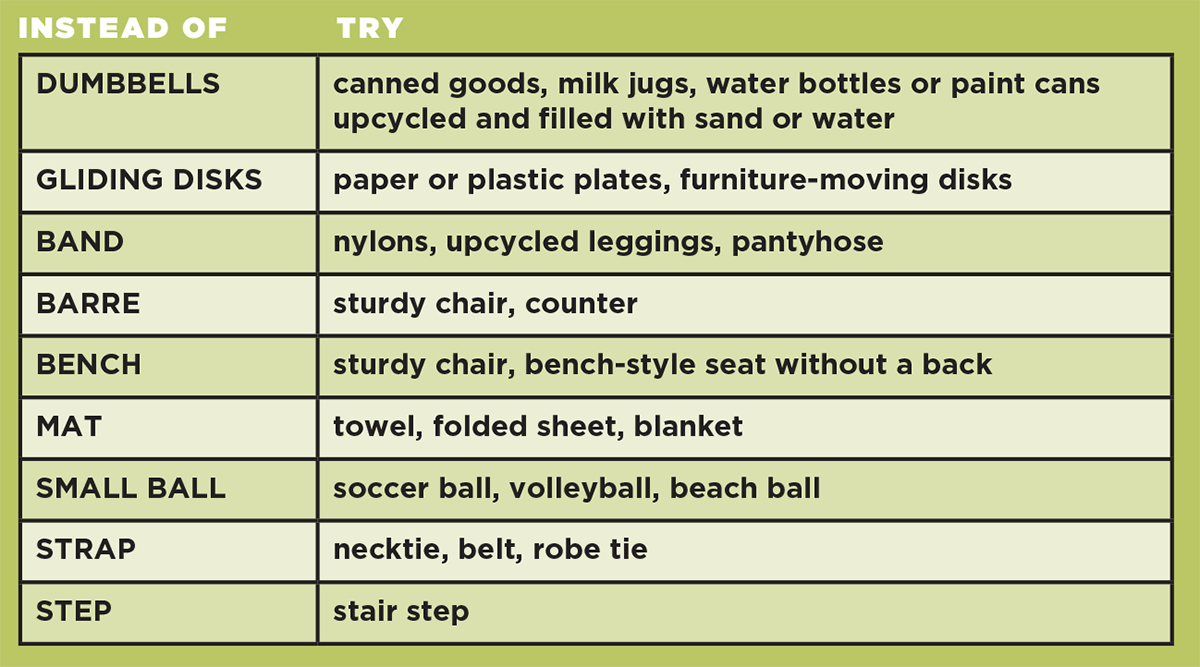

Nontraditional Small-Equipment Options

If your virtual participants don’t have access to traditional small equipment, no problem! Suggest some of these creative household options:

Which Small Equipment Will Work?

Key Movement Principles for a Varied Workout

Part of your small-equipment workout “recipe” involves increasing movement complexity by including multiple planes of motion, motor learning or greater task complexity. Below are some examples to add to your class design.

Load refers to either body-weight training (which remains a constant) or adding an external force, such as dumbbells or resistance bands.

Lever length can increase or decrease intensity. For example, performing a biceps curl with elbow close to the body, instead of extended, makes the curl less challenging.

Changing up hand and foot placement also adds variety and challenge to a move. In alternating side-to-side lunges, you can place the weight on the floor as you lunge to the side, then pick it up on the next set—increasing the challenge on subsequent repetitions.

Moving the center of mass also affects movement difficulty. Transitioning from a stationary lunge to a one-foot pike shifts mass forward.

Changing speed or tempo is another effective, easy way to boost intensity. For example, teaching a bent-over row at a 4:2 tempo, then switching it up for the second set, will task the muscles differently and mix things up.

Transitions can add a valuable tweak. Transitioning from a squat to an alternating lunge makes the move harder.

Power is the final component in this recipe. Power is a measurement of work output and a function of force and velocity. Force can be in the form of load, while speed can be in the form of tempo. For example, in a body-weight squat, the load doesn’t change unless you add an external force. Therefore, to increase power in a body-based exercise, you need to change velocity. One way to do this is to add a jump to the squat (a change in velocity), which increases power output.

Give These Small-Equipment Exercises a Try!

To stimulate your own creativity, here are a few moves to try in your next group fitness class. All you’ll need are a set of dumbbells, a resistance band (tubing with handles) and body weight. However, use whatever equipment you have available, and mix and match the foundational moves. Start the class with a warmup (beginning with the posterior chain), cover all the foundational movements and wrap up with flexibility training.

- squat, with floor touch / power = squat jumps

- row with leg extensions / power = fast alternating extensions

- alternating front lunges, with dumbbell pass under lead leg / power = jumping jacks

- narrow squat with reverse fly / power = single-leg gallop on the spot

- lunge side, lunge back, with heel taps 4x / power = taps to heel jumps

- wide squat with lat pulldowns into calf raise / power = wide jumps

- torso rotation 3x, with touch down and switch jump / power = switch jumps

- hinge to single-leg pike / power = tempo leg lifts

- forward lunge with balance lift / power = repeater knee lifts

- shoulder press and carry / power = quarter-turn speed hops

- triceps extension with side leg lifts / power = high-knee jumps

- plank into spiderman / power = donkey kicks

- seated, side lateral raise / power = mini jumps

- burpees / power = tempo burpees

- pushups (wide, medium, narrow) / power = tempo pushups

- bicycles, 1-2-3 with leg lift / power = tempo bicycles

- V-sit, farmer’s lift / power = up and over with dumbbells

Krista Popowych

Krista Popowych inspires fitness leaders, trainers and managers around the globe with her motivating sessions. She is the 2014 IDEA Fitness Instructor of the Year and a three-time (2016, 2008, 2003) canfitpro Canadian Fitness Presenter of the YearShe is Keiser’s global director of education, as well as a Balanced Body® master trainer, JumpSport® consultant, DVD creator, published writer, Adidas-sponsored fit pro and IDEA Group Fitness Committee member.