Dieting Makes You Fat! How?

No doubt many IDEA Fitness Journal readers saw news reports earlier this year saying that contestants in the 2009 season of The Biggest Loser had regained a substantial proportion of the weight they lost in the popular reality show.

The media were reporting on a 2016 article (Fothergill et al. 2016) in the journal Obesity which found that more than half of the 14 contestants (6 men and 8 women) had regained a significant amount of weight 6 years after the contest. New research offers intriguing scientific explanations for why it happened.

Weight Loss Changes Resting Metabolic Rate

To see why the Biggest Loser contestants didn’t keep their weight off, we need to start by reviewing a few fundamentals of human metabolism. First, let’s look at the three contributors to the body’s total energy expenditure (TEE):

- Resting metabolic rate. RMR measures the energy the body uses to maintain cellular homeostasis.

- Thermic effect of food.This is the energy the body uses to digest, absorb, transport, metabolize and store the foods we eat. It’s about 10% of TEE.

- Physical activity-induced energy expenditure. This is the energy used for exercise and spontaneous movement (Wang et al. 2000).

Wang et al. (2000) note that RMR accounts for about 60%–75% of the body’s total energy expenditure when measured after an overnight fast; that’s substantially more than physical activity or digestion of food.

In their review of the Biggest Loser contestants’ results, Fothergill et al. (2016) explain that weight loss slows the body’s RMR—a phenomenon called “metabolic adaptation” or “adaptive thermogenesis.” Essentially, the slower metabolic rate from weight loss encourages the body to regain that weight.

Big Losses, Big Regains

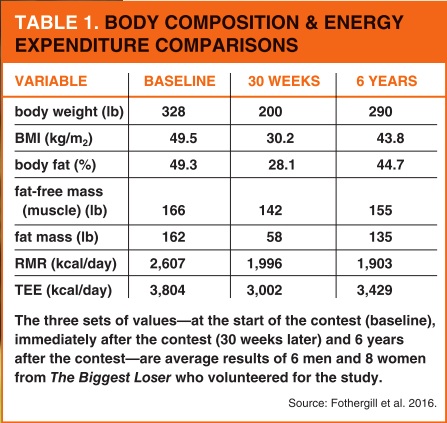

The Fothergill et al. (2016) Biggest Loser study measured several physiological parameters and RMR (determined by indirect calorimetry) at three points in the contestants’ lives: at baseline (just before the competition), 30 weeks later (as soon as the competition ended) and 6 years after that (see Table 1 for some of these assessments).

On average, the 14 contestants

- lost 128 pounds in the 30-week exercise and nutrition competition, but regained an average of 90 pounds by the 6-year follow-up;

- lost 24 pounds of muscle in the vigorous 30-week program, but regained 13 pounds of muscle by the 6-year follow-up; and

- lost an average of 104 pounds of fat in 30 weeks, but regained 77 pounds by the 6-year assessment.

RMR measurements produced some of the most startling results. After 30 weeks, the contestants’ average RMR had plunged 611 kilocalories below their baseline. Surprisingly, at the 6-year follow-up, average RMR had fallen another 93 kcal from the 30-week level. So, from baseline to 6-year follow-up, RMR sank an average of 704 kcal. This was the data supporting the “dieting makes you fatrdquo; hypothesis.

Key Links in Dieting, Weight Gain Rate

Fothergill et al. (2016) observed some hormonal and biomarker changes (in appetite) after the contest, but their research was not statistically powerful enough to be conclusive. However, Sumithran et al. (2011), who observed 50 obese participants (34 completed the study), revealed that 1 year of intentional weight loss (striving for a 10% loss of body weight) produced significant changes in biomarkers for appetite, hunger and fat deposition (e.g., leptin, peptide YY, cholecystokinin, insulin, ghrelin, gastric inhibitory polypeptide and pancreatic polypeptide)—and all those changes promoted weight gain. The future of successful weight management will eventually require the development of safe, effective, long-term treatments to counteract these metabolic adaptations (Sumithran et al. 2011). (An upcoming research column will look in more detail at the various biomarkers related to weight regain.)

Did Rapid Weight Loss Influence Contestants’ Weight Regain?

Many fitness professionals may suspect that the rapid weight loss of Biggest Loser contestants contributed to their weight regain. However, recent studies cited by Fothergill et al. (2016) do not support the idea that the rate of weight loss affects long-term weight regain.

What Other Factors Affect the “Diets Make You Fat” Phenomenon?

Pietiläinen et al. (2012) collected and reported weight changes (taken by surveys) of 4,129 individual twins in Finland from the population-based FinnTwin16 study at 16, 17, 18 and 25 years past baseline. The researchers confirmed that dieting may lead to the opposite of the desired outcome.

The authors hypothesized that restrictive diets may lead some people to become preoccupied with food, which triggers overeating. They added that the suppression of metabolic rate and loss of lean mass (noted in Biggest Loser contestants) may help lead to a postdiet weight rebound.

This seemingly defensive reaction to dieting clearly shows that the body tries to restore lost weight. Additionally it suggests that the phenomenon could persist beyond the point of weight restoration, leading to further weight gain. Pietiläinen et al. (2012) concluded that genetics also plays a substantial role in weight regain for some people.

What Should Fitness Pros Do to Prevent Weight Regain?

The Biggest Loser and several studies confirm that we know how to develop successful weight loss programs that combine exercise, nutrition and behavior modification. Unfortunately, we have a lot less data on preventing people from regaining lost weight. Nevertheless, results from a study of people in the National Weight Control Registry, who lost an average of 73 pounds and maintained a significant loss for more than 5 years, offer several key strategies (listed above) (Wing & Phelan 2005).

Interestingly, approximately one-half of registry members reported having been overweight as a child, and almost 75% had one or two parents who were obese, concurring with the Pietiläinen et al. (2012) finding that there’s a consequential genetic component to weight gain.

The National Registry database confirms that long-term weight loss maintenance is achievable. Wing & Phelan (2005) suggest that initially, as professionals, we need to define successful weight loss, which they suggest is intentionally losing 10% of body weight and keeping it off for at least 1 year. The authors suggest that 10% is an effective standard because losing that much weight can drive meaningful reductions in the risk factors for heart disease and type 2 diabetes. From their evaluation of their research combined with other studies, Wing & Phelan (2005) estimate that about 20% of overweight people successfully lose 10% of body weight and keep it off for a year.

Additionally, Wing & Phelan (2005) emphasize that people who have maintained weight loss for 2–5 years show even greater chances for longer-term success.

The authors state that most successful weight loss maintenance involves high levels of physical activity, representing about 1 hour per day of moderate-intensity (i.e., somewhat hard) activity, such as brisk walking. This is equivalent to an average of 2,545 kcal per week in physical activity for women and 3,293 kcal per week for men (Wing & Phelan 2005).

The sidebar “Strategies That Help Maintain Long-Term Weight Loss” lists the most common behaviors of people who have lost at least 10% (and often much more) of their body weight and prevented weight regain. With strategic planning and client education, exercise professionals can help determined clients prioritize the workable steps to lose (and keep off) meaningful amounts of weight. It may be challenging, but it is definitely doable!